Differentiating between type 1 and type 2 diabetes: what are the challenges?

Diabetes presents in many ways and people with diabetes often have nonspecific symptoms that can be difficult to classify at onset. The correct diagnosis is important to manage diabetes and prevent complications. This article details cases illustrating the evaluation of different types of diabetes and covers autoantibody testing and C-peptide testing.

- There is significant variety in the presentation of diabetes, and symptoms can be nonspecific.

- Correct diabetes subtype identification will direct appropriate treatment, although subtype classification may not always be clear at the time of diagnosis and may require re-evaluation over time.

- Interpretation of autoantibody tests and glucose and C-peptide levels in diabetes can be complex.

- Appropriate management helps facilitate prevention of diabetes complications.

- The primary care setting is responsible for the management of most people with diabetes, particularly in the early stages, and the involvement of endocrinologists is essential when managing complex subtypes.

- People with diabetes should be educated on their therapies and side effects, particularly because the treatment landscape continues to evolve rapidly.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are heterogeneous diseases and can share similar features. Distinguishing between diabetes types can be challenging at onset, and classification may need to be reviewed over time as the degree of pancreatic beta-cell deficiency becomes more obvious.1 With rising obesity rates in children, it can be difficult to differentiate between T1D and T2D based on clinical findings. A diagnosis of T1D does not preclude having components of metabolic syndrome, which are typically associated with T2D. The correct diagnosis is important for appropriate management, follow up and prevention of complications. There are also important subtypes of both major forms of diabetes, which can influence the choice of therapy. Recognising these subtypes can help optimise individualised management. Several cases are used to illustrate the evaluation of diabetes types, including the use of autoantibody testing for assessment of autoimmunity and C-peptide testing for assessment of endogenous insulin production.

Case A. Type 1 diabetes

Samantha, a 28-year-old woman, presents to the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Her blood glucose level (BGL) is 28 mmol/L with a ketone level of 5.8 mmol/L and pH 6.9. Investigations indicate severe urosepsis. She is admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment with intravenous fluids, intravenous insulin infusion, electrolyte replacement and antibiotics. Her glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level is 91 mmol/mol (10.7%) with positive glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) autoantibodies (more than 2000 U/mL) and tyrosine phosphatase-related islet antigen (IA-2) antibodies (more than 2000 U/mL). She is given the diagnosis of T1D and provided with diabetes education. On discharge, she starts continuous glucose monitoring with a multiple daily injection insulin regimen initiated, including long-acting insulin detemir twice daily, as well as rapid-acting insulin aspart with meals.

What are the features of T1D?

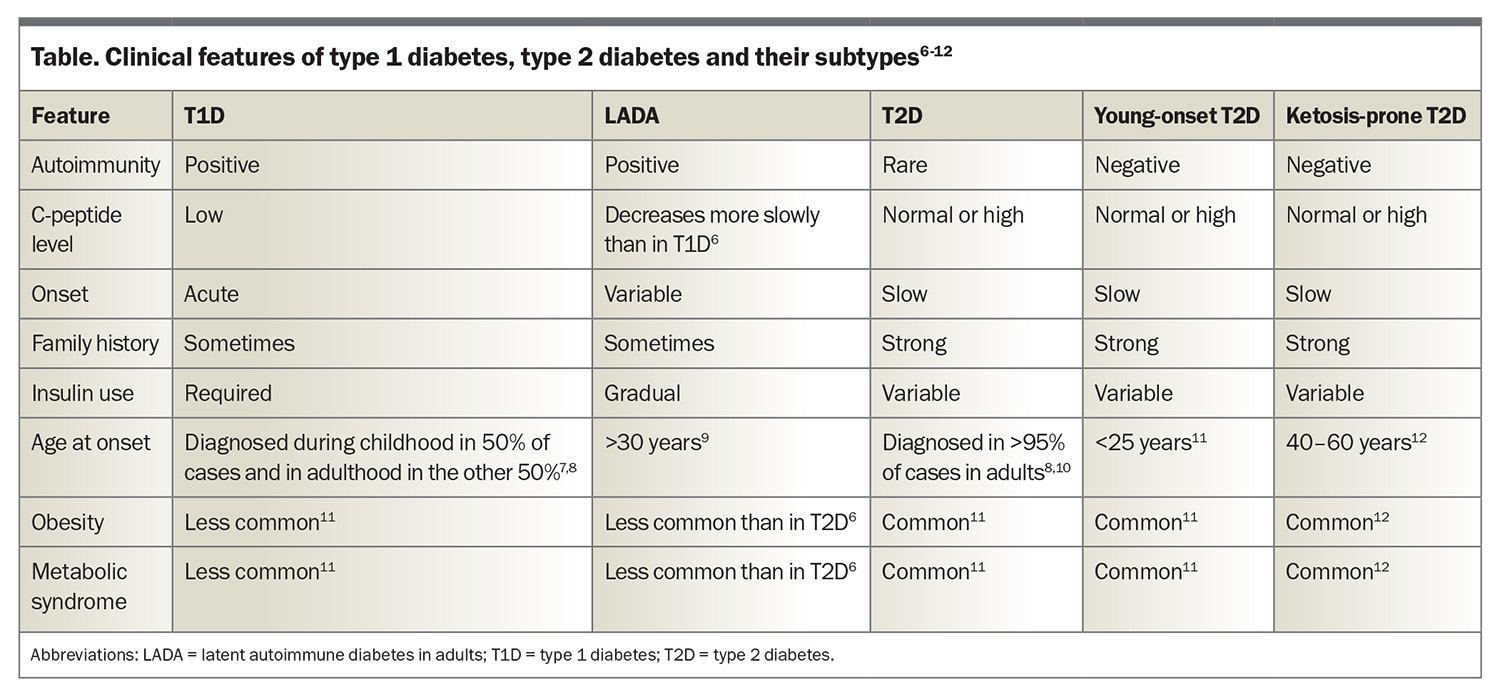

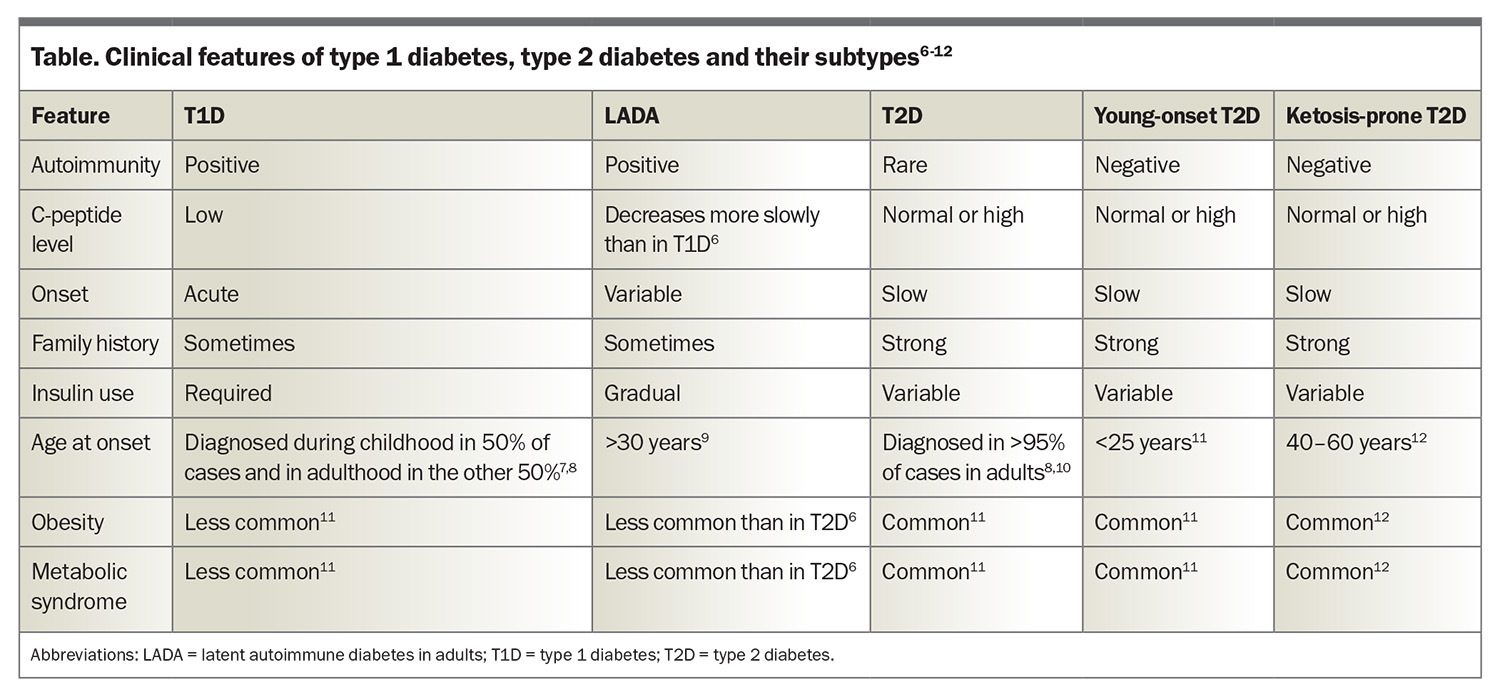

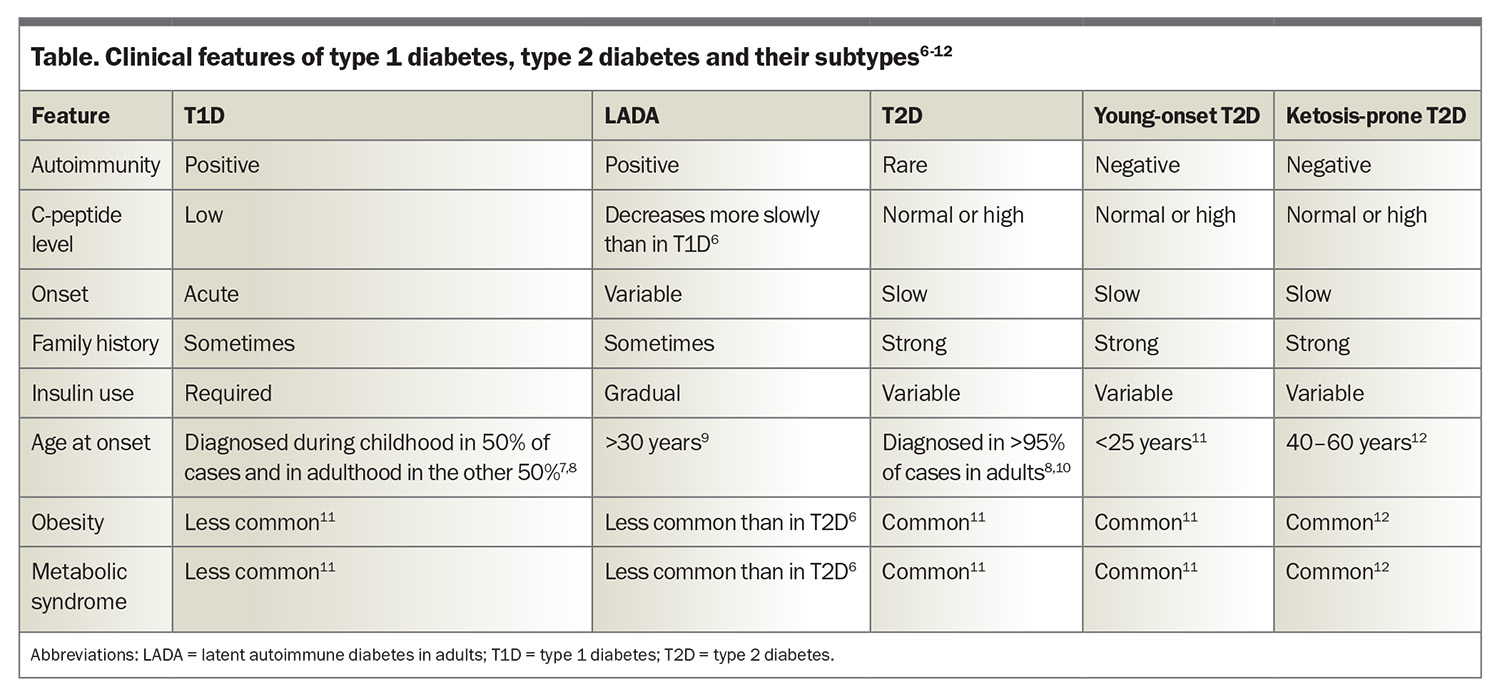

T1D is an autoimmune disease with both genetic and environmental contributions. It is characterised by the loss of pancreatic beta cells (responsible for insulin production), leading to a relative or absolute insulin deficiency.1-3 Consequently, hyperglycaemia and ketosis occur, which can result in DKA. More than 90% of people with T1D have at least one positive autoantibody, with the remaining people often referred to as having antibody-negative disease.2,4 C-peptide is produced from the cleavage of proinsulin and is used as a marker of pancreatic beta cell function. A low-to-normal C-peptide level in the context of hyperglycaemia is suggestive of relative insulin deficiency.5 Treatment involves administration of insulin through either multiple daily injections or pump therapy. It is important also to screen for other autoimmune conditions, including coeliac disease and thyroid disease. The clinical features of T1D are summarised in the Table.6-12

What is the role of autoantibodies in diabetes?

Four main antibodies are tested for in clinical practice when assessing the type of diabetes: GAD, IA-2, zinc transporter 8 and insulin. Both IA-2 and insulin antibody titres have been associated with more rapid disease progression of beta-cell destruction.13 Studies have demonstrated that higher titres and positivity for two or more autoantibodies are linked with a greater risk of development of T1D.14-16

The development of T1D can be classified in stages occurring at variable rates: stage 1 is the presence of two or more islet autoantibodies with normoglycaemia; stage 2 is the presence of autoantibodies with dysglycaemia and is presymptomatic; and stage 3 is the presence of symptomatic disease.2 T1D screening programs are being developed utilising autoantibody testing.

Case B. Type 2 diabetes

Xavier, a 65-year-old man, presents to the outpatient clinic for review. His medical background includes ischaemic heart disease with three coronary artery stents, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, previous transient ischaemic attack and two digit amputations. He feels well, without symptoms of hyperglycaemia, and has clinical and biochemical features of metabolic syndrome. He is found to have a new diagnosis of T2D with an HbA1c of 118 mmol/mol (13%). After medical review, in addition to care from a diabetes educator and dietitian, he commences extended release metformin 500 mg twice daily and empagliflozin 10 mg daily, with a view to considering semaglutide, depending on his clinical response.

What are the features of T2D?

T2D is by far the most common type of diabetes, accounting for 87.6% of diabetes in Australia, followed by T1D, accounting for 9.6%.17 The disease process in T2D is characterised by impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance or both. Dysregulation of the metabolism involved in carbohydrates, lipids, proteins and adipocytes is a part of the progression of disease.18 As a result, people with T2D often develop metabolic syndrome and have a higher rate of microvascular complications than those with T1D.19 T2D is highly heterogeneous and further subgrouping is being assessed in a research setting to assist with prognostication of diabetes complication risks.20 The clinical features of T2D are summarised in the Table.6-12

How does metabolic syndrome affect T2D?

Treating the underlying features and factors of metabolic syndrome has been associated with an improvement in glycaemic profiles, and correcting triglyceride levels has been associated with an improvement in insulin resistance.6 Additionally, treating blood pressure to target and producing weight loss of at least 5% can improve glycaemia and reduce insulin requirements.21 However, there is an independent risk of microvascular complications with the presence of metabolic syndrome.22

Case C. Slowly evolving immune-mediated diabetes

Piper, a 48-year-old woman, presents to the outpatient diabetes clinic for a review of her diabetes. She was diagnosed at 35 years old with T2D, after a hospital admission for hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome (HHS). At the time she was placed on insulin due to HHS but was then lost to follow up. On review, her BGLs are very labile, with morning and evening hypoglycaemia. She is receiving small doses of insulin glargine at night and aspart with meals. Further biochemistry is performed, finding a low C-peptide level of 0.18 nmol/L (180 pmol/L) (normal range: 0.26–1.4 nmol/L [260–1400 pmol/L]) and mildly positive GAD antibodies.

What is slowly evolving immune-mediated diabetes?

Slowly evolving immune-mediated diabetes is latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), a type of diabetes that likely forms part of the spectrum that encompasses T1D. Typically, individuals with LADA are older than 30 years with a gradual onset of T1D.23,24 Consequently, the initiation of insulin therapy is usually delayed, and it is estimated that the prevalence in Australia is less than 1%.25 About 5% of people with T2D are misdiagnosed and instead have LADA.26,27 The Table illustrates the clinical features of LADA.6-12

How is LADA recognised?

Screening for LADA is the same as screening for T1D: blood testing that includes a C-peptide level and autoantibodies. GAD antibody is the most common type of autoantibody present.24,27 Individuals with LADA tend to be more lean than is typically seen in T2D, and the presence of positive GAD autoantibodies predicts a more rapid progression to requiring insulin.27 Clues that might suggest LADA is present include an absence of metabolic syndrome or extreme insulin sensitivity. It is recommended that clinicians in the community should have a low threshold for screening people with these features. Although autoantibodies can burn out with time, there is still a role for assessing them and pancreatic beta-cell function.

People who should be considered for screening for T1D and LADA include those with:

- a relative with T1D

- a new onset of diabetes at younger than 60 years of age

- presentations of ketosis or DKA

- insulin sensitivity

- labile BGLs with hypoglycaemia

- presence of other autoimmune conditions.

Case D. Young-onset type 2 diabetes

James, a 19-year-old man, presents to the emergency department with symptoms suggestive of hyperglycaemia, including polydipsia, polyuria, fatigue, unintentional weight loss and dizziness, that have been present for several months. His family history is significant for maternal T2D, as well as all three siblings having T2D. His initial set of blood test results show hyperglycaemia (BGL, 18.5 mmol/L) but no sign of acidosis or ketonaemia. His HbA1c on admission was 158 mmol/mol (15.9%), and his body mass index was 31 kg/m2. His serological testing is negative for T1D autoantibodies and his C-peptide level is 0.361 nmol/L (361 pmol/L) (normal range: 0.26–1.4 nmol/L [260–1400 pmol/L]). He is commenced on glargine once daily due to his glucotoxicity and extended release metformin 500 mg twice daily, with a view to considering other therapies such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors once the polyuria improves, as well as incretin-based therapies.

What is young-onset T2D?

The past decade has witnessed a 37% rise in the prevalence of T2D in adolescents and young adults, with 42,131 individuals under 39 years of age currently living with T2D in Australia.28 Factors causing this increase include lower socioeconomic status, a sedentary lifestyle, metabolic syndrome, family history of diabetes, hyperglycaemia during pregnancy and conditions that predispose to insulin resistance (such as polycystic ovarian syndrome and metabolic associated fatty liver disease).27 The Table illustrates the clinical features of young-onset T2D.6-12

How is young-onset T2D distinguished from other types of diabetes?

Clinical features associated with young-onset T2D include the following:27,29

- insulin resistance

- metabolic syndrome

- obesity

- polycystic ovarian syndrome

- absence of autoimmune conditions

- often asymptomatic

- higher risk of cardiovascular disease

- higher prevalence of microvascular complications

- more common in Indigenous populations

- family history of T2D.

The psychological impact of this diagnosis is important because it significantly affects the mental, physical and emotional aspects of an individual’s life. Those with T2D have a higher risk of microvascular complications, and due to early exposure to prolonged hyperglycaemia, their cardiovascular risk is also higher and requires aggressive management.27,29,30

Case E. Ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes

Bill, a 22-year-old man, presents to the emergency department with a two-month history of polydipsia, polyuria and weight loss but feels well. His past medical history includes hypercholesterolaemia. On review, his BGL level is 16.4 mmol/L with a ketone level of 3.4 mmol/L and no acidosis. His HbA1c level is 149 mmol/mol (15.1%), his C-peptide level is 0.78 nmol/L (780 pmol/L) (normal range: 0.26–1.4 nmol/L [260–1400 pmol/L]) with concurrent hyperglycaemia (glucose 18 mmol/L) and he tests negative for T1D autoantibodies. He is subsequently commenced on metformin extended-release 500 mg twice daily with modified-release gliclazide 60 mg twice daily.

Three months later, he re-presents to the emergency department with community-acquired pneumonia. His biochemistry indicates that he has hyperglycaemia with significant ketosis and no sign of acidosis. After treating his infection, he is discharged home with glargine once daily in addition to his oral therapies.

How is ketosis-prone diabetes different from other forms of diabetes?

Ketosis-prone diabetes is a form of diabetes that is often considered a hybrid of T1D and T2D. As with T1D, ketosis and DKA are common features, and the biochemical parameters are similar, with lower insulin requirements than T2D.31 It has been shown that people with ketosis-prone diabetes can regain beta-cell function and discontinue insulin therapy as time progresses,32 although there can be recurrences with physiological stressors. As with T2D, metabolic syndrome and obesity are common traits. There is often a strong family history and evidence of a functional beta-cell reserve.31,32 The Table illustrates the clinical features of ketosis-prone diabetes.6-12

What is the management approach to ketosis-prone diabetes?

Individuals with ketosis-prone diabetes are prone to DKA, particularly in the short term. Insulin therapy is often utilised in the short-term management of people with ketosis-prone diabetes, with a gentle wean often successful over time. Lifestyle interventions, including dietary changes and regular exercise with weight loss, are important.33 Additionally, building up strong lifestyle habits can help individuals develop self-management skills to assist in decreasing the long-term disease burden. It has been shown that 75% of people with ketosis-prone diabetes enter a remission phase and that non-insulin therapies may be an effective part of management once remission has occurred.34,35

Conclusion

Diabetes is increasing in prevalence, and the initial diagnosis and management often take place in a primary care setting. People with diabetes can present with nonspecific symptoms and diabetes can be missed when an individual first presents to primary care or the emergency department. Distinguishing between types of diabetes can be difficult. Referral of patients to a specialist centre is critical when the type of diabetes is not clear and/or when glycaemic targets are not reached. The recognition of the different subtypes of diabetes allows for appropriate management and monitoring. Performing autoantibody testing is important in the differentiation of these subtypes. Treatment involving a multidisciplinary team helps ensure that individuals develop appropriate management skills and receive treatment with optimal agents. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Clifford: None. Dr Lee has received speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly; and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Eli Lilly.

References

1. Committee ADAPP. 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes - 2025. Diabetes Care 2025; 48: S27-S49.

2. Insel R, Dunne J, Atkinson M, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1964-1974.

3. Norris J, Johnson R, Stene L. Type 1 diabetes - early life origins and changing epidemiology. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8: 226-238.

4. Andersson C, Vaziri-Sani F, Lindblad B, et al. Triple specificity of ZnT8 autoantibodies in relation to HLA and other islet autoantibodies in childhood and adolescent type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2012: 1-10.

5. Maddaloni E, Bolli G, Frier B, et al. C-peptide determination in the diagnosis of type of diabetes and its management: A clinical perspective. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2022; 24: 1912-1926.

6. Buzzetti R, Tuomi T, Mauricio D, et al. Management of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: a consensus statement from an international expert panel. Diabetes 2020; 69: 2037-2047.

7. Arffman M, Hakkarainen P, Keskimaki I, Oksanen T, Sund R. Long-term and recent trends in survival and life expectancy for people with type 1 diabetes in Finland. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2023; 198: 198-204.

8. Rewers M. Challenges in diagnosing type I diabetes in different populations. Diabetes Metab J 2012; 36: 90-97.

9. Fourlanos S, Dotta F, Greenbaum C, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) should be less latent. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 2206-2212.

10. Hillier T, Pedula K. Characteristics of an adult population with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: the relation of obesity and age of onset. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1522-1527.

11. Lascar N, Brown J, Pattison H, Barnett A, Bailey C, Bellary S. Type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 69-80.

12. Alawdi S, Al-Dholae M, Al-Shawky S. Metabolic syndrome and pharmacotherapy outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc 2024; 5: 1-10.

13. Felton J, Redondo M, Oram R, et al. Islet autoantibodies as precision diagnostic tools to characterize heterogeneity in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Commun Med 2024; 4: 1-18.

14. Jia X, Yu L. Understanding islet autoantibodies in prediction of type 1 diabetes. J Endocr Soc 2024; 8: 1-8.

15. Grace S, Bowden J, Walkey H, Simell O, et al. Islet autoantibody level distribution in type 1 diabetes and their association with genetic and clinical characteristics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022; 107: 4341-4349.

16. Ziegler A, Rewers M, Simell O, et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA 2013; 309: 2473-2479.

17. ABS. Diabetes: Contains key statistics and information about diabetes and its prevalence in Australia; 2022. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/diabetes/latest-release (accessed January 2025).

18. DeFronzo R, Ferrannini E, Groop L, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis 2015; 1: 1-22.

19. Dabelea D, Stafford J, Mayer-Davis E, et al. Association of type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with complications during teenage years and young adulthood. JAMA 2017; 317: 825-835.

20. Ahlqvist E, Storm P, Käräjämäki A, et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 361-369.

21. Lee M, Kim M, Koh E, Kim E, Nam G, Kwon H. Changes in metabolic syndrome and its components and the risk of type diabetes: a nationwide cohort. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 2313-2321.

22. Asghar S, Asghar S, Shahid S, Fatima M, Bukhari S, Siddiqui S. Metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: prevalence, risk factors, and associated microvascular complications. Cureus 2023; 15: 1-9.

23. Fadiga L, Saraiva J, Catarino D, Frade J, Melo M, Paiva I. Adult-onset autoimmune diabetes: comparative analysis of classical and latent presentation. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2020; 12: 1-9.

24. O’Neal K, Johnson J, Panak R. Recognizing and appropriately treating latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Diabetes Spectr 2016; 29: 249-252.

25. Davis W, Peters K, Makepeace A, et al. The prevalence of diabetes in Australia: insights from the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. Intern Med J 2018; 48: 803-809.

26. Manisha A, Shangali A, Mfinanga S, Mbugi E. Prevalence and factors associated with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA): a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord 2022; 22: 1-9.

27. Jones A, McDonald T, Shields B, Hagopian W, Hattersley A. Latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA) is likely to represent a mixed population of autoimmune (type 1) and nonautoimmune (type 2) diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: 1243-1251.

28. Diabetes Australia. 2023 Snapshot: Diabetes in Australia; 2023. Available online at: https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023-Snapshot-Diabetes-in-Australia.pdf (accessed January 2025).

29. Wong J, Ross G, Zoungas S, et al. Management of type 2 diabetes in young adults aged 18-30 years: ADS/ADEA/APEG consensus statement. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 422-429.

30. Group TS, Zeitler P, Hirst K, et al. A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2247-2256.

31. Sjöholm A. Ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes: a case series. Sec Clinical Diabetes 2019; 10: 1-7.

32. Boike S, Mir M, Rauf I, et al. Ketosis-prone diabetes mellitus: A phenotype that hospitalists need to understand. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10: 10867-10872.

33. Smolenski S, George N. Management of ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2019; 31: 430-436.

34. Lebovitz H, Banerji M. Ketosis-prone diabetes (flatbush diabetes): an emerging worldwide clinically important entity. Curr Diab Rep 2018; 18: 1-8.

35. Colloby M. Ketosis-prone diabetes: identification and management. J Diabetes Nurs 2014; 18: 352-360.