Type 2 diabetes management: what’s new?

A major paradigm shift has occurred in how we manage patients with type 2 diabetes. Weight loss with intensive diet and lifestyle interventions can result in remission of type 2 diabetes. Medications are now chosen based on patient characteristics and comorbidities (e.g. presence of chronic kidney disease and heart failure, weight and cardiovascular risk), as well as PBS indications.

- Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors now have indications beyond diabetes. They are also now indicated for heart failure with both reduced and preserved ejection fraction and chronic kidney disease independent of type 2 diabetes.

- A new PBS change from 1 June 2024 means a patient must ‘fail’ an SGLT-2 inhibitor before glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) can be prescribed.

- GLP-1 RAs are not only effective glucose-lowering agents and induce meaningful weight loss, but they also reduce the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events. Similar cardiovascular benefits have been shown in obese patients without diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease.

- Recent clinical trials have also shown that semaglutide slows the progression of chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, which are the first clear data showing the renal protection effects of GLP-1 RAs.

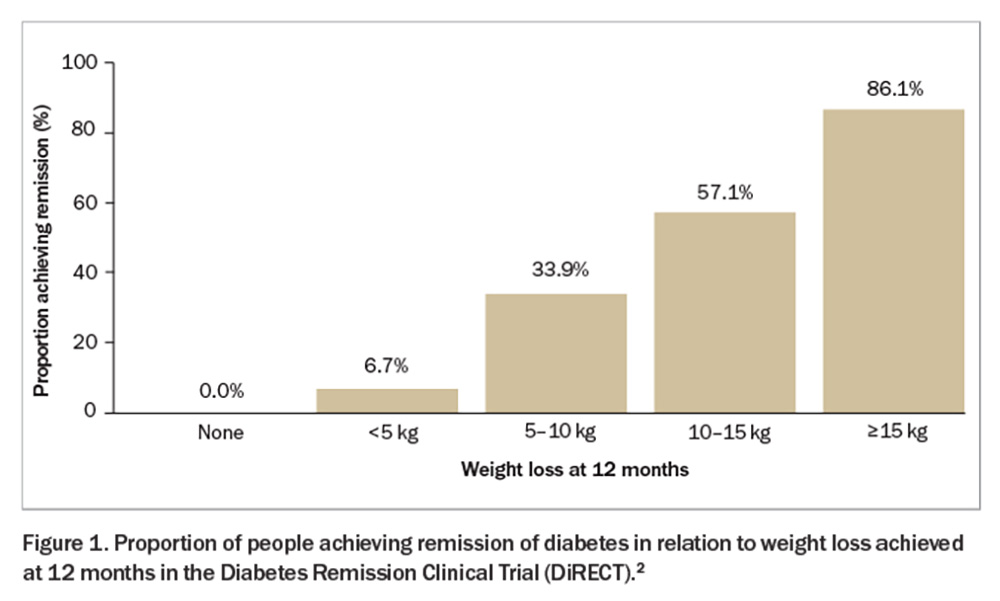

- An intensive weight management program (diet and lifestyle intervention) can result in type 2 diabetes remission, which is proportional to the amount of weight loss. Weight loss of 10 to 15 kg and more than 15 kg results in a 57% and 86% chance of diabetes remission, respectively. It appears that with weight regain, diabetes will return.

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder characterised by insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is rising globally, posing significant challenges to healthcare systems worldwide. Between the years 2000 and 2020, there was almost a three-fold increase in people living with diabetes in Australia, from 460,000 to 1.3 million.1 About 50,000 Australians were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in 2021.1

GPs play a crucial role in the diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes because of their frequent patient encounters and comprehensive approach to healthcare delivery. This article provides GPs with the latest insights and practical recommendations in type 2 diabetes management, including lifestyle interventions, medical management, new indications for current therapies and PBS updates.

Can remission of type 2 diabetes be achieved?

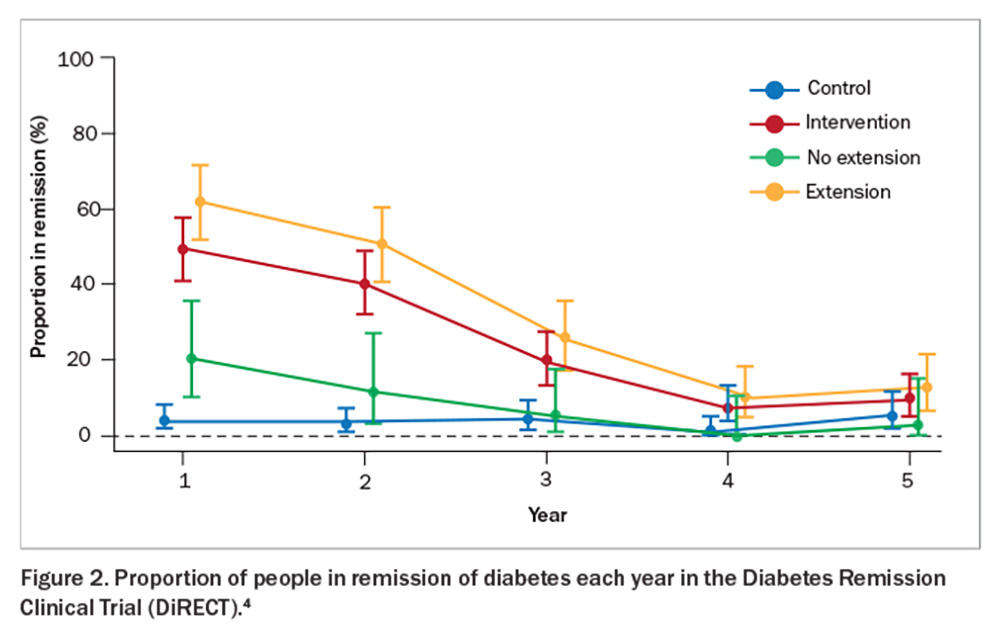

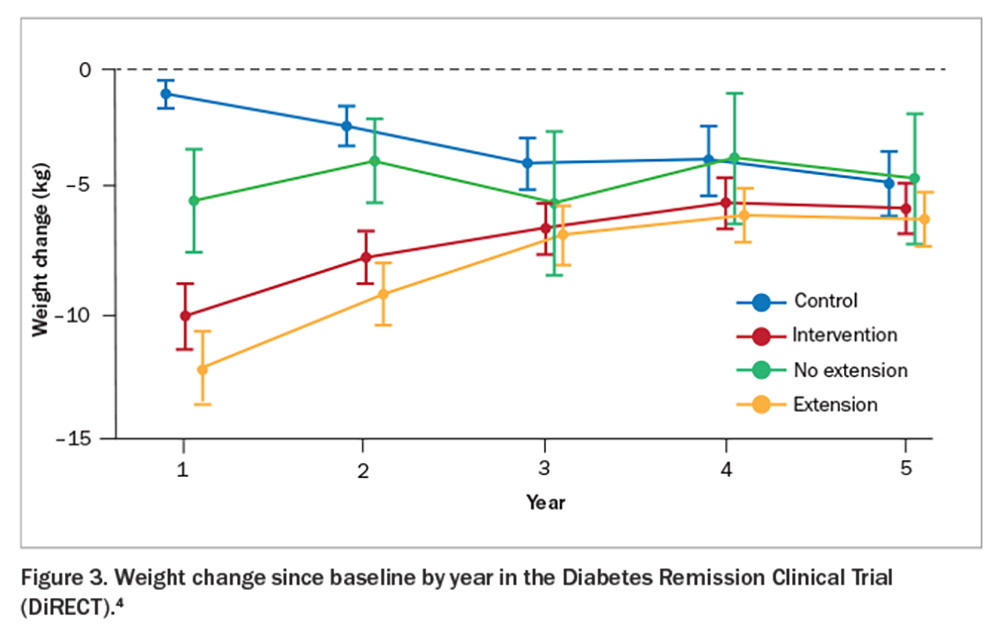

The Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) showed that sufficient weight loss can induce remission of type 2 diabetes (Figure 1).2 This trial compared a weight management program (intervention) with best-practice care (control) in primary care (49 practices) in the UK and recruited 306 individuals aged 20 to 65 years who had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes within the past six years, had a body mass index (BMI) of 27 to 45 kg/m2 and were not receiving insulin. The intervention included withdrawal of antidiabetic and antihypertensive medications, total diet replacement (3452 to 3569 kJ/day formula diet for three to five months), stepped food reintroduction (two to eight weeks) and structured support for long-term weight loss maintenance. The co-primary outcomes were weight loss of 15 kg or more and remission of diabetes defined as a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level of less than 6.5% after at least two months off all antidiabetic medications, from baseline to 12 months. The results showed remission rates of 7% (0 to 5 kg weight loss), 34% (5 to 10 kg weight loss), 57% (10 to 15 kg weight loss) and 86% (>15 kg weight loss). This trial was recently replicated in an Australian primary care setting (DiRECT-Aus).3 The five-year follow up of DiRECT was recently published. After two years of follow up, intervention participants were offered continued low-intensity support (once every three months) for a subsequent three years (extension group = 68% of the intervention group) versus no regular follow up (no extension). At five years, the results showed an average weight loss of 6.1 kg with 13% remaining in remission in the intervention group (Figure 2 and Figure 3).4 Patients with longer-term type 2 diabetes are likely to have lower rates of remission, and realistic goals are crucial to avoid a sense of failure. Furthermore, those in remission should continue with complication screening and cardiovascular risk modifications. Although bariatric surgery is not widely available on a population level, metabolic surgery is also effective for attaining diabetes remission.

To summarise, an intensive weight management program run in primary care can induce type 2 diabetes remission. Weight loss of 10 to 15 kg and more than 15 kg results in remission of type 2 diabetes in 57% and 86% of patients, respectively, at 12 months. Long-term remission can be achieved if weight regain is minimised.

Paradigm shift in type 2 diabetes management

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors

The type 2 diabetes world changed with the presentation of the Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) trial at the European Association of the Study of Diabetes meeting in Stockholm in 2015.5 Previous cardiovascular outcome trials had shown that the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (gliptins) showed no impact on major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).6,7 These phase 4 trials were mandated by the FDA, after the apparent increase in MACE with the use of rosiglitazone after a review published in 2007.8 The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial demonstrated that patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events who received empagliflozin had a significant 14% reduction in MACE. It also demonstrated a significant reduction in secondary endpoints of cardiovascular death, hospitalisations for heart failure and death from any cause.5 Moreover, there was a suggestion of renal protection (which led the way for the subsequent heart failure and renal-specific trials). This trial changed the way we use pharmacological agents to manage type 2 diabetes. We now use medications not only for glycaemic control, but also to promote an individualised approach by choosing medications for additional benefits based on patient characteristics and comorbidities. The use of SGLT-2 inhibitors has become widespread across general practice, endocrinology, cardiology and nephrology. The relevant safety concerns are addressed in patient resources, which highlight sick day rules and the requirement to withhold before surgery (see: www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/1154380/SGLT2-inhibitor-Patient-Information.pdf).

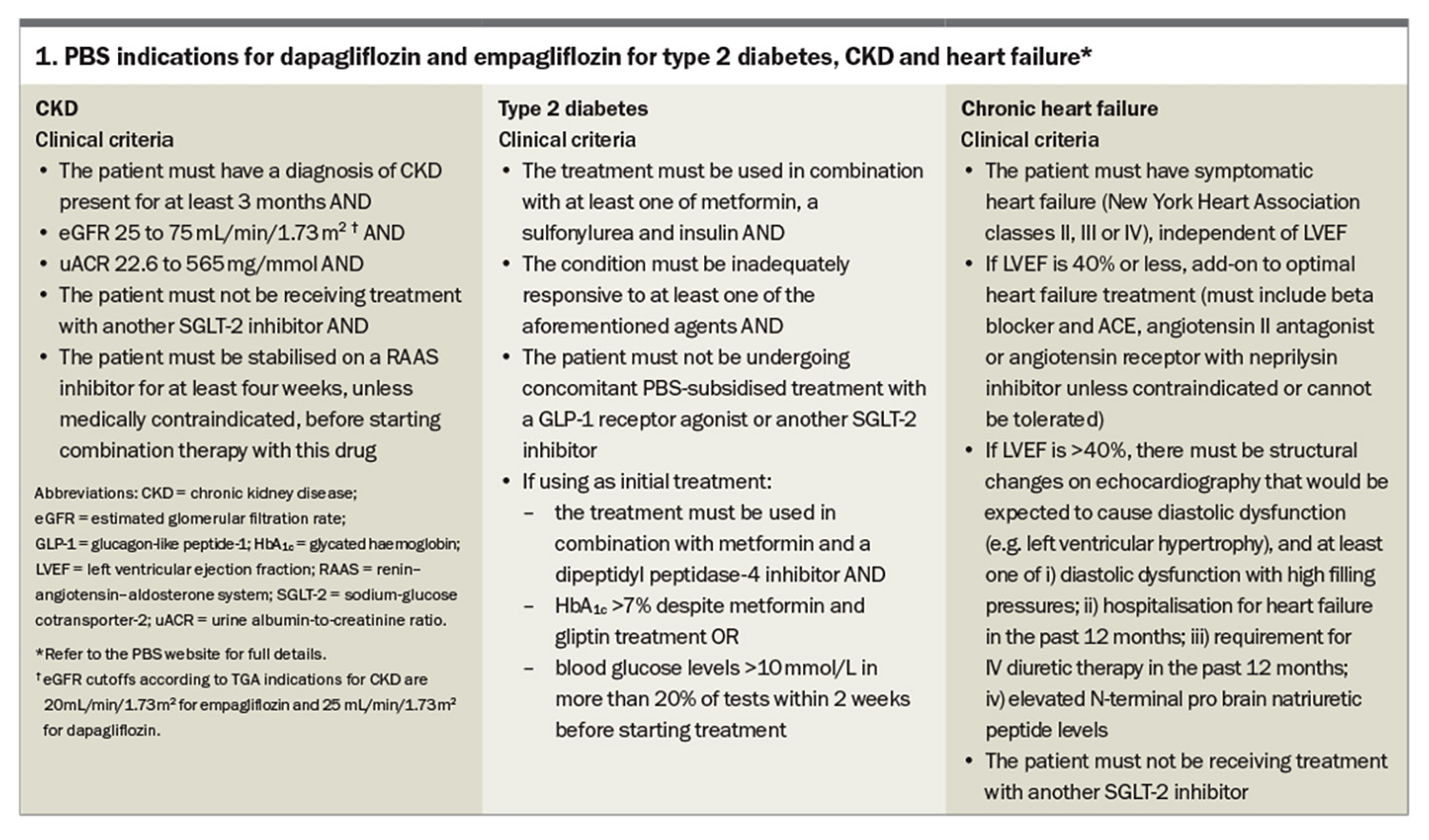

Since the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown benefits in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), as well as a reduction in MACE.9-14 In fact, the SGLT-2 inhibitors (empagliflozin and dapagliflozin) now have PBS listings (streamlined authority required) for HFrEF, HFpEF and CKD independent of diabetes status (i.e. these benefits are seen independent of the glucose-lowering effect) (Box 1). This is the first class of medication in 20 years to slow the progression of CKD. Similarly, SGLT-2 inhibitors are the first class of medication with level 1 evidence to be indicated for HFpEF. There are estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) cutoffs for initiating patients on SGLT-2 inhibitors, which are as follows:

- dapagliflozin: do not initiate if eGFR is less than 25 mL/min/1.73 m2, but continue if the patient is already on with approval from a nephrologist

- empagliflozin: do not initiate if eGFR is less than 20 mL/min/1.73 m2, but continue if the patient is already on with approval from a nephrologist.

These eGFR cutoffs are not because of additional adverse events, but because of a current lack of data (more trials are coming soon). Reassuringly, in patients without type 2 diabetes, there appears to be minimal risk for genital fungal infections, urinary tract infections and other adverse effects, including euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis (or SGLT-2 inhibitor-induced diabetic ketoacidosis which can also occur with higher blood glucose levels); however, patient awareness of sick day management remains important (see: www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/1154380/SGLT2-inhibitor-Patient-Information.pdf).

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists

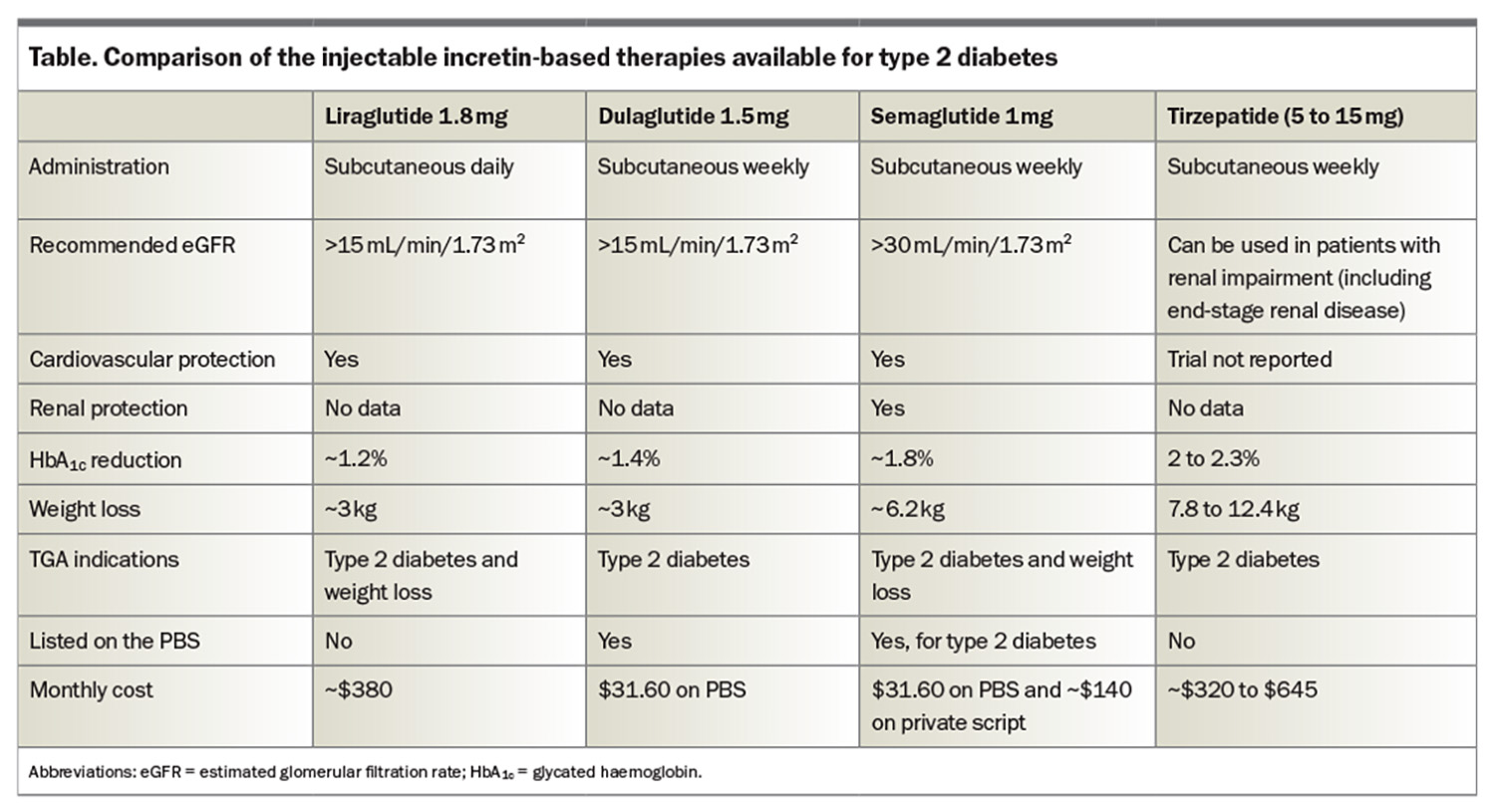

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor coagonist are among the newest medications for people with type 2 diabetes. These incretin-based medications have been shown to have impressive HbA1c and weight reduction benefits (Table), but potentially, and more importantly, they also reduce MACE. Liraglutide is a once-daily GLP-1 RA and is also TGA approved for weight loss (but not PBS listed; cost on private prescription is $380 per month). Liraglutide was the first GLP-1 RA to demonstrate a significant reduction in MACE in patients with type 2 diabetes.15 Dulaglutide was the first weekly GLP-1 RA to show a MACE benefit in the dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND) trial.16 Of note, most patients in the REWIND trial had risk factors but not established cardiovascular disease. Subsequently, semaglutide (0.5 mg or 1.0 mg weekly) also showed a MACE benefit in the Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes with Semaglutide in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes (SUSTAIN 6).17 The recently published Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People with Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) trial has generated an enormous amount of interest, reporting a 20% reduction in MACE following introduction of high-dose semaglutide (2.4 mg weekly) in obese patients without diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease (i.e. these benefits are independent of glucose-lowering effects).18

Recently, the Evaluate Renal Function with Semaglutide Once Weekly (FLOW) trial was published.19 The trial was stopped early due to interim analysis showing statistical benefit in renal endpoints. In this study, 3533 patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD (eGFR of 50 to 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio 33.9 to 565 mg/mmol or an eGFR of 25 to 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 11.3 to 565 mg/mmol) were randomised to receive semaglutide 1 mg or placebo. There was a statistically significant 24% reduction in progression of CKD and death from kidney-related or cardiovascular causes, including a 21% reduction in kidney-specific endpoints (dialysis or transplantation, at least a 50% reduction in eGFR from baseline or eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2). Semaglutide slowed the annual decline in eGFR by 1.16 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p<0.001). These are the first clear data showing the renal protection effects of GLP-1 RAs.

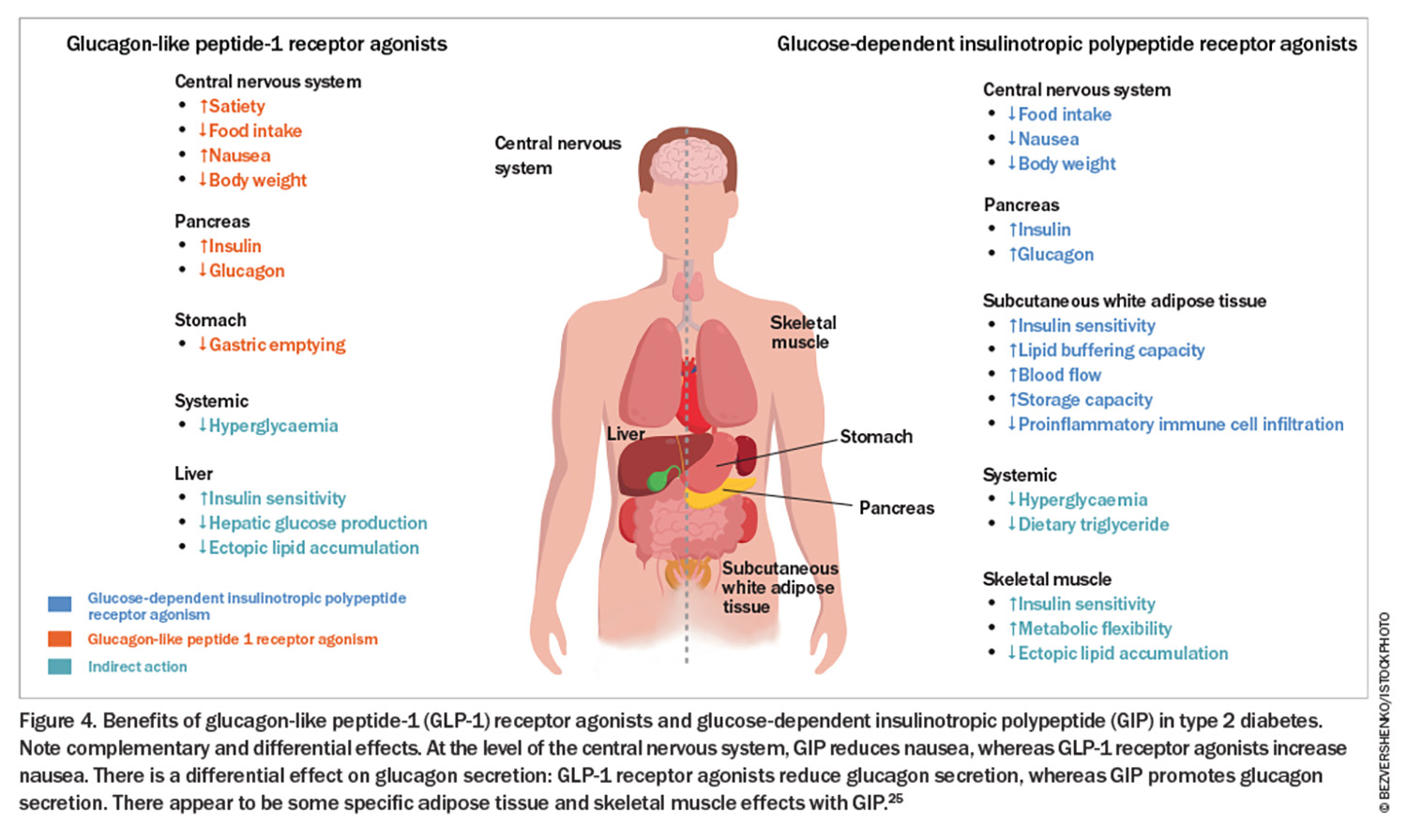

Tirzepatide is the first-in-class dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist. In a head-to-head trial (patients with type 2 diabetes), tirzepatide at doses of 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg outperformed semaglutide at a dose of 1 mg. The estimated mean change from baseline in HbA1c was 1.86% for semaglutide and 2.01%, 2.24% and 2.3% with 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg of tirzepatide, respectively. The changes in body weight were 6.7% with 1 mg semaglutide and 8.5%, 11% and 13.1% with 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg of tirzepatide, respectively.20 Of note, tirzepatide has not been trialled against high-dose semaglutide (2.4 mg), which is the dose employed in weight loss trials and is now available in Australia for the treatment of overweight and obesity in the FlexTouch pen device at doses and cost per month of 0.25 mg ($260), 0.5 mg ($260), 1.0 mg ($260), 1.7 mg ($380) and 2.4 mg ($460). Despite tirzepatide requiring injections with a vial, needle and syringe (a new multidose device option is available this month) and no PBS listing (cost ranges from $320 to $645 per month), this medication sold out in Australia within three months (available again from mid-February 2024). The weight loss benefits observed with the use of semaglutide and tirzepatide are far better in patients without type 2 diabetes. The SURMOUNT-1 trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide in adults with obesity or overweight who did not have diabetes and reported weight losses of 16%, 21.4% and 22.5% at 72 weeks with 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg of tirzepatide, respectively.21 The Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity (STEP-1) trial demonstrated 14.9% body weight loss at 68 weeks with semaglutide 2.4 mg.22 Recent studies following withdrawal of these therapies do show weight regain in the majority of patients, suggesting that long-term treatment is required.23,24 A summary of the incretin effects is shown in Figure 4.25 It is an exciting time for the management of type 2 diabetes, with a number of other injectable and oral therapies in the pipeline. A Study of Tirzepatide Compared With Dulaglutide on Major Cardiovascular Events in Participants With Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS-CVOT) is due to report in 2025–26.

Adjunctive therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes to address complications

Retinopathy

It is worth revisiting the use of fenofibrate to slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Data from the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study demonstrated benefits in patients with moderate to severe nonproliferative retinopathy, proliferative retinopathy and macular oedema.26 Fenofibrate needs to be renally adjusted (if eGFR is >60 mL/min/1.73 m2, the dose should be 145 mg; if eGFR is 30 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, start with 48 mg daily and increase to 96 mg daily if no adverse effects on renal function are observed). A rapid drop in HbA1c level can worsen pre-existing retinopathy but it is important to note that this is not a medication-specific effect.17

Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease

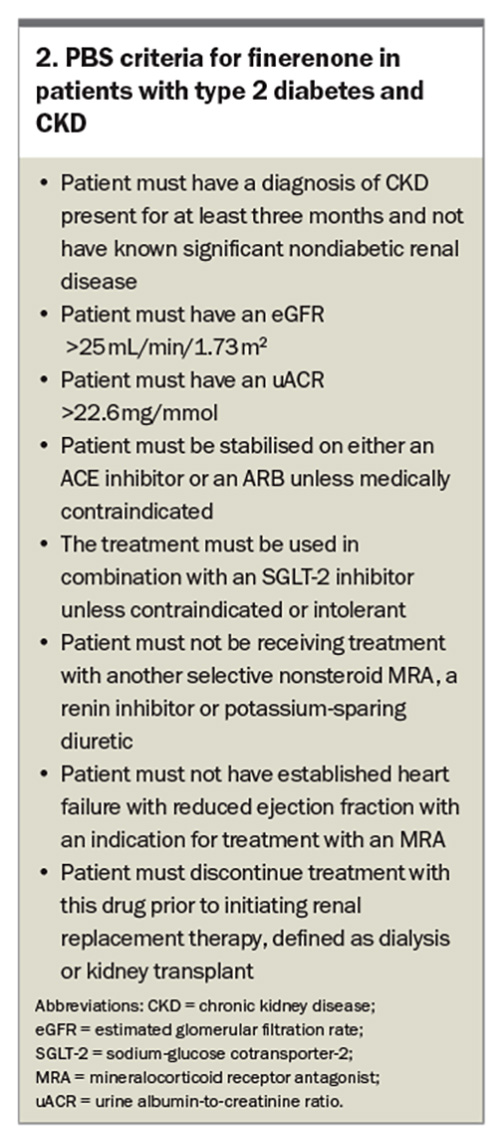

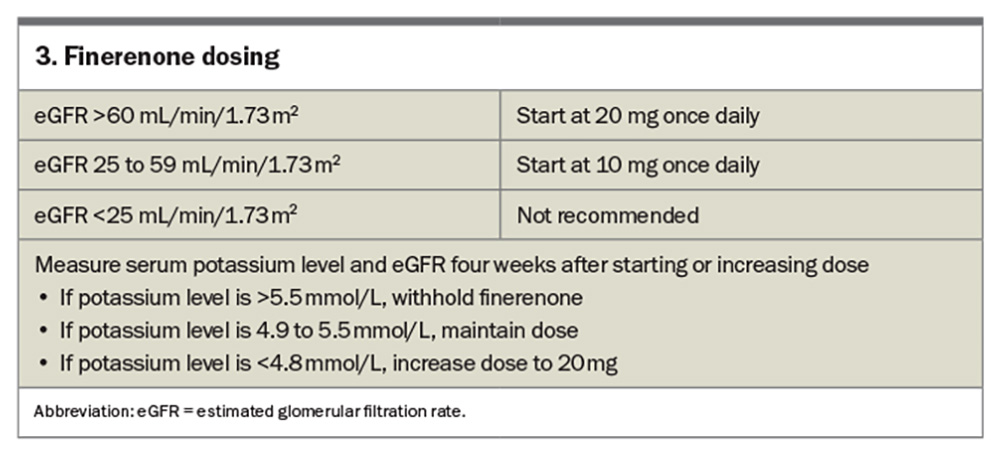

Finerenone, a selective nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), received its PBS listing (streamline authority required) for use in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD on 1 July 2023 (Box 2). The Efficacy and Safety of Finerenone in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Clinical Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIGARO-DKD) trial and Finerenone in Reducing Kidney Failure and Disease Progression in Diabetic Kidney Disease (FIDELIO-DKD) trial were undertaken and looked at a four-point MACE (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalisation for heart failure) and renal endpoints (at least 40% reduction in eGFR, need for renal replacement therapy or death from renal causes).27,28 Patients had an eGFR range of 25 to 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and varied levels of albuminuria (albumin- to-creatinine ratio of 3.4 to 565 mg/mol) depending on the trial. All patients were stabilised on renin-angiotensin system treatment before initiation of finerenone. Both trials achieved significance, with the FIGARO-DKD trial demonstrating a 13% relative risk reduction in MACE and the FIDELIO-DKD trial demonstrating an 18% reduction in renal endpoints. Finerenone was ceased in 1.2% of patients in the FIGARO-DKD trial and 2.3% of patients in the FIDELIO-DKD trial because of hyperkalaemia (see Box 3 on finerenone dosing).

Cardiovascular disease

Although aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease is established practice, aspirin or other antiplatelet therapy is not recommended for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Earlier studies of aspirin in the primary prevention setting were undertaken when the use of blood pressure and statin therapy was less widespread. A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes (ASCEND) evaluated the role of aspirin in the primary prevention of serious vascular events in people with type 2 diabetes, and although a modest reduction in MACE was observed, this was offset by an increase in major bleeding.29

Icosapent ethyl is a highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (a component of fish oil) that demonstrated a significant 25% cardiovascular risk reduction for hypertriglyceridaemia.30 It is TGA approved to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in statin-treated patients at high cardiovascular risk with elevated triglyceride levels (≥1.7 mmol/L) and established cardiovascular disease or diabetes, and at least one other cardiovascular risk factor. It should become available for use in Australia later in 2024.

Navigating the PBS and type 2 diabetes treatment algorithm

The pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes has changed dramatically over the past 20 years. In the 2000s, the thiazolidinediones (rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) entered the market, adding a third option to metformin and sulfonylureas. The DPP-4 inhibitors (initially sitagliptin, then saxagliptin, linagliptin, vildagliptin and alogliptin) soon followed. The PBS was relatively easy to navigate at this point. However, immediate-release exenatide entered the market in 2010, and the SGLT-2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin, followed by empagliflozin) in 2013, and it became complex. It seemed the PBS was being updated to reflect which DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT-2 inhibitor, GLP-1 RA could be used in combination – without forgetting insulin. In the late 2010s, the new indications discussed in this article added further complexity. DPP-4 inhibitors should be ceased when GLP-1 RAs are prescribed as they have no therapeutic effect in this setting (act on same pathway). The PBS does not subsidise coprescription of GLP-1 RAs and SGLT-2 inhibitors for diabetes management; however, there is evidence to support the concomitant use of these agents.31

The GLP-1 RAs no longer have streamlined authority codes for new initiations. On 1 June 2024, changes were made to the restrictions of several medicines listed on the PBS for the treatment of type 2 diabetes to implement recommendations made by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in March 2023, July 2023 and March 2024. These changes aim to simplify and clarify the PBS restrictions, ensure use in accordance with the PBS restrictions, and align the restrictions with current clinical guidelines while considering the cost effectiveness of comparative treatments. The restriction changes were recommended following PBAC consideration of a utilisation analysis examining the extent of use of type 2 diabetes medicines outside of the current PBS restrictions. Relevant consumer and prescriber groups and sponsor companies were consulted regarding the restriction changes.32 It was reported that almost 60% of people prescribed GLP-1 RA appeared to be on a regimen inconsistent with PBS guidelines. GLP-1 RAs prescribing has risen from 7% (2017–18; cost about $37 million) to 26% (2021–22; cost $193 million), with GLP-1 RAs now the most expensive type 2 diabetes medication on the PBS.32

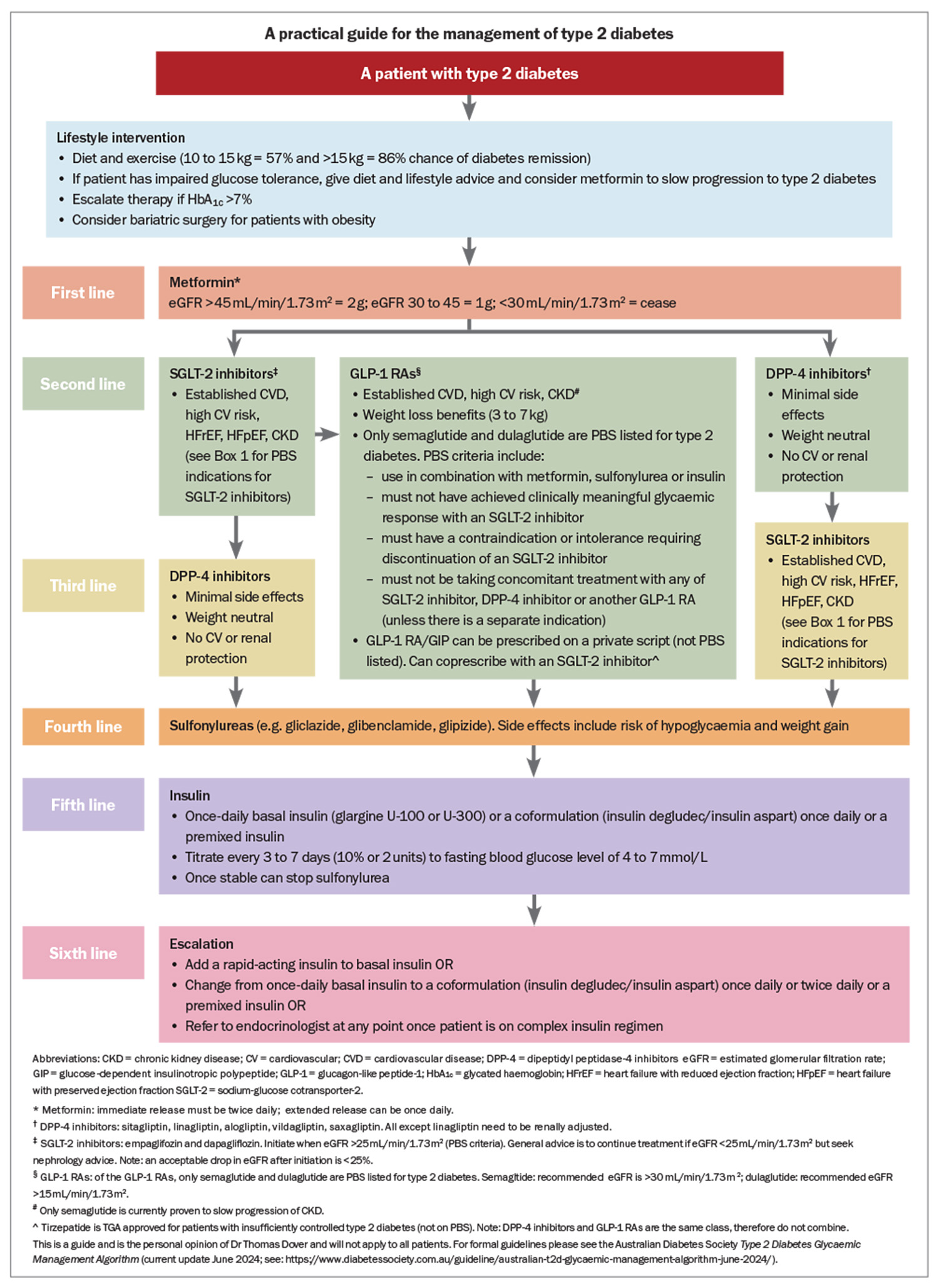

In summary, to prescribe a GLP-1 RA after metformin, the patient must trial an SGLT-2 inhibitor and not have a clinically meaningful glycaemic response or they must have a contraindication or intolerance to an SGLT-2 inhibitor. If the patient has a separate indication for a SGLT-2 inhibitor (e.g. heart failure or CKD as outlined above), then coprescription is allowed. The Australian Diabetes Society Type 2 Diabetes Glycaemic Management Algorithm is regularly updated (current update June 2024; see: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/guideline/australian-t2d-glycaemic-management-algorithm-june-2024/) and the Living Evidence Guidelines in Diabetes aims to keep clinicians up to date with the latest changes.33 A practical treatment guide from the use of metformin to insulin, taking into consideration patient factors and the PBS to guide prescribing, is shown in the Flowchart. This is not a replacement for the nationwide guidelines/algorithm, but an aid to simplify the common treatment approaches for GPs.

Summary

A major paradigm shift has occurred in the management of type 2 diabetes. Remission has been shown with weight loss as a result of diet and lifestyle interventions and should always be the cornerstone of practice. Medications are now chosen based on patient characteristics and comorbidities (e.g. CKD, HFrEF, HFpEF, cardiovascular risk and weight) and the PBS indications. We have never been in a better position to help our patients with type 2 diabetes manage glycaemic control, risk factors and diabetes complications. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Dover has received honoraria for lectures and presentations from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Boheringer-Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Abott, Sanofi, Medtronic, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Novartis, Amgen; support for meetings from Novo Nordisk, Boehringer-Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Ypsopump, Lilly; and is on Advisory Boards for Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca and Novartis. Dr Phillips has received honoraria for educational activities and events from Eli Lilly, GSK, Novo Nordisk, Servier; and travel support for attending meetings from Novo Nordisk.

References

1. Australian Government. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Diabetes: Australian facts Canberra: AIHW; 2024.. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/diabetes/contents/how-common-is-diabetes/type-2-diabetes (accessed August 2024).

2. Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018; 391; 391: 541-551.

3. Hocking SL, Markovic TP, Lee CM, et al. Intensive lifestyle intervention for remission of early type 2 diabetes in primary care in Australia: DiRECT-AUS. Diabetes Care 2024; 47: 66-70.

4. Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. 5-year follow-up of the randomised Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) of continued support for weight loss maintenance in the UK: an extension study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2024; 12: 233-246.

5. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117-2128.

6. Green JB, Bethal AM, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 232-242.

7. Rosenstock J, Perkovic V, Johansen OE, et al. Effect of linagliptin vs placebo on major adverse cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular and renal risk. JAMA 2019; 321: 69-79.

8. Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2457-2471.

9. McMurray JV, Solon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1995-2008.

10. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1413-1424.

11. Solomon SD, McMurray JV, Claggett B, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 1089-1098.

12. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 1451-1461.

13. Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1436-1446.

14. The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 117-127.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 311-322.

16. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 121-130.

17. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1834-1844.

18. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen KB, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med 2023; 389: 2221-2232.

19. Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, et al. Effects of semaglutide on chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2024; 39: 109-121.

20. Frias JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 503-515.

21. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 205-216.

22. Wilding JP, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 989-1002.

23. Wilding JP, Batterham RL, Davies M, et al. STEP 1 Study Group. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab 2022; 24: 1553-1564.

24. Aronne LJ, Sattar N, Horn DB, et al. Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity: The SURMOUNT-4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024; 331: 38-48.

25. Samms RJ, Coghlan MP, Sloop KW, et al. How May GIP enhance the therapeutic efficiency of GLP-1? Trends Endocrinol Metab 2020; 31: 410-421.

26. Keech AC, Mitchell P, Summanen PA, et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD Study): a RCT. Lancet 2007; 370: 1687-1697.

27. Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 2252-2263.

28. Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2219-2229.

29. "ACEND Study Group. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1529-1539.

30. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 11-22.

31. SinghAK, Singh R. Metabolic and cardiovascular benefits with combination therapy of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. World J Cardiol 2022; 14: 329-342.

32. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). PBS restriction changes to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) medicines Canberra: PBS; 2024. Available online at: https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/reviews/pbs-restriction-changes-to-type-2-diabetes-mellitus-t2dm-medicines (accessed August 2024).

33. Australian Diabetes Society (ADS). Living Evidence Guidelines in Diabetes Sydney: ADS; 2024. Available online at: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/living-evidence-guidelines-in-diabetes/ (accessed August 2024).