Improving outcomes for people with diabetes-related foot disease

Diabetes-related foot disease is common and, in some cases, has devastating consequences for those affected. Regular screening, timely assessment and prompt skilled management can improve patient outcomes.

- Diabetes-related foot disease is common and associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

- Categorisation of ulceration risk is important in directing screening frequency and preventive care.

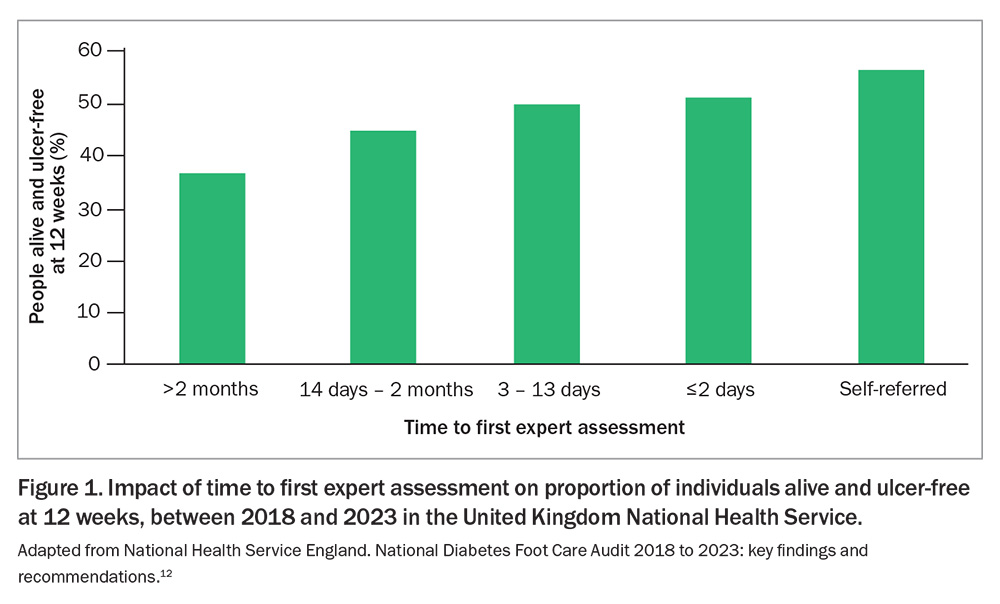

- For people with diabetes-related foot ulceration, time to first expert assessment is a key predictor of outcome.

- For people with suspected active Charcot foot, immediate pressure offloading and immobilisation are crucial for safe care.

- Ensuring equitable access to standard care across Australia for people with diabetes-related foot disease is a significant issue.

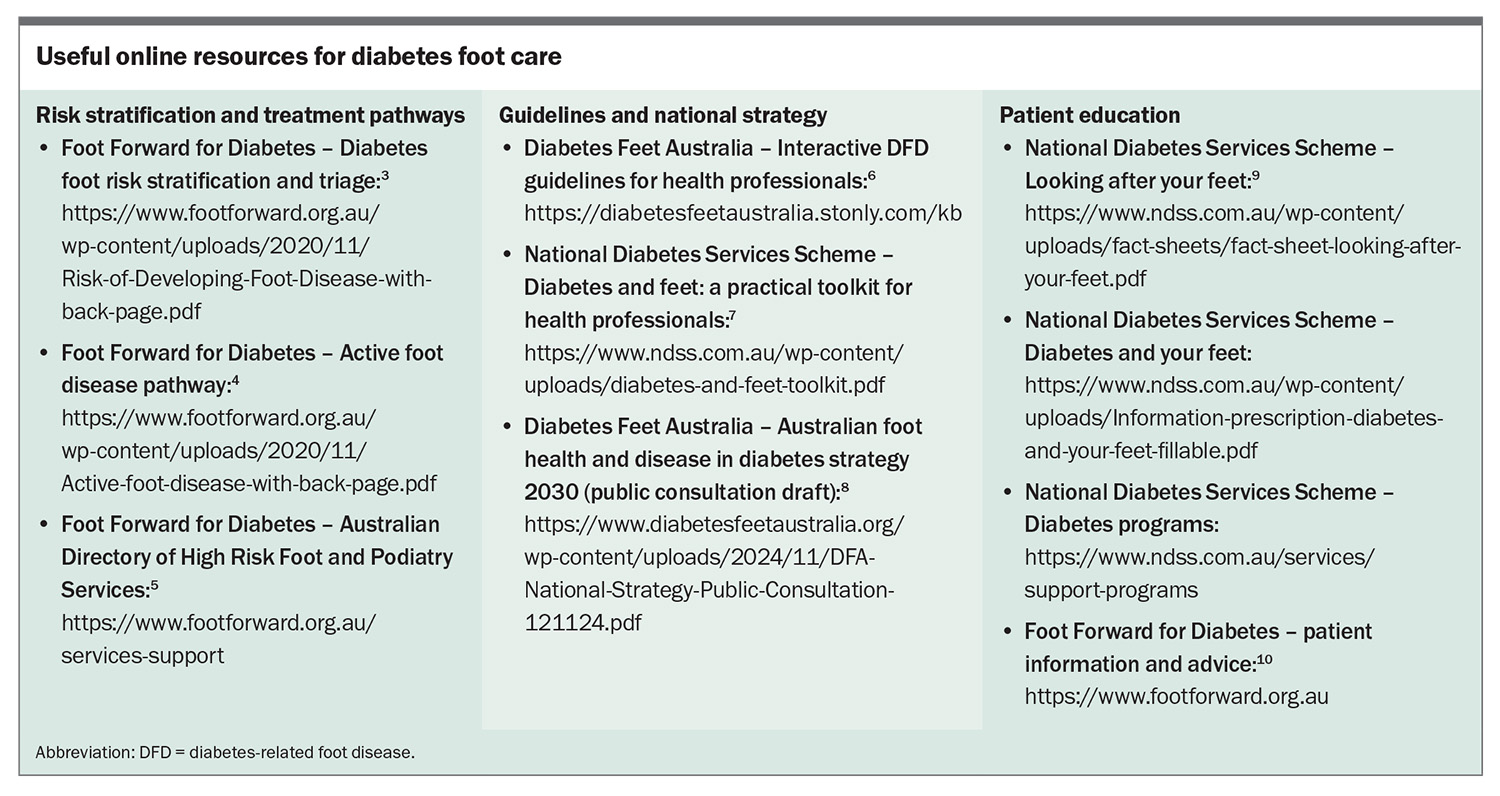

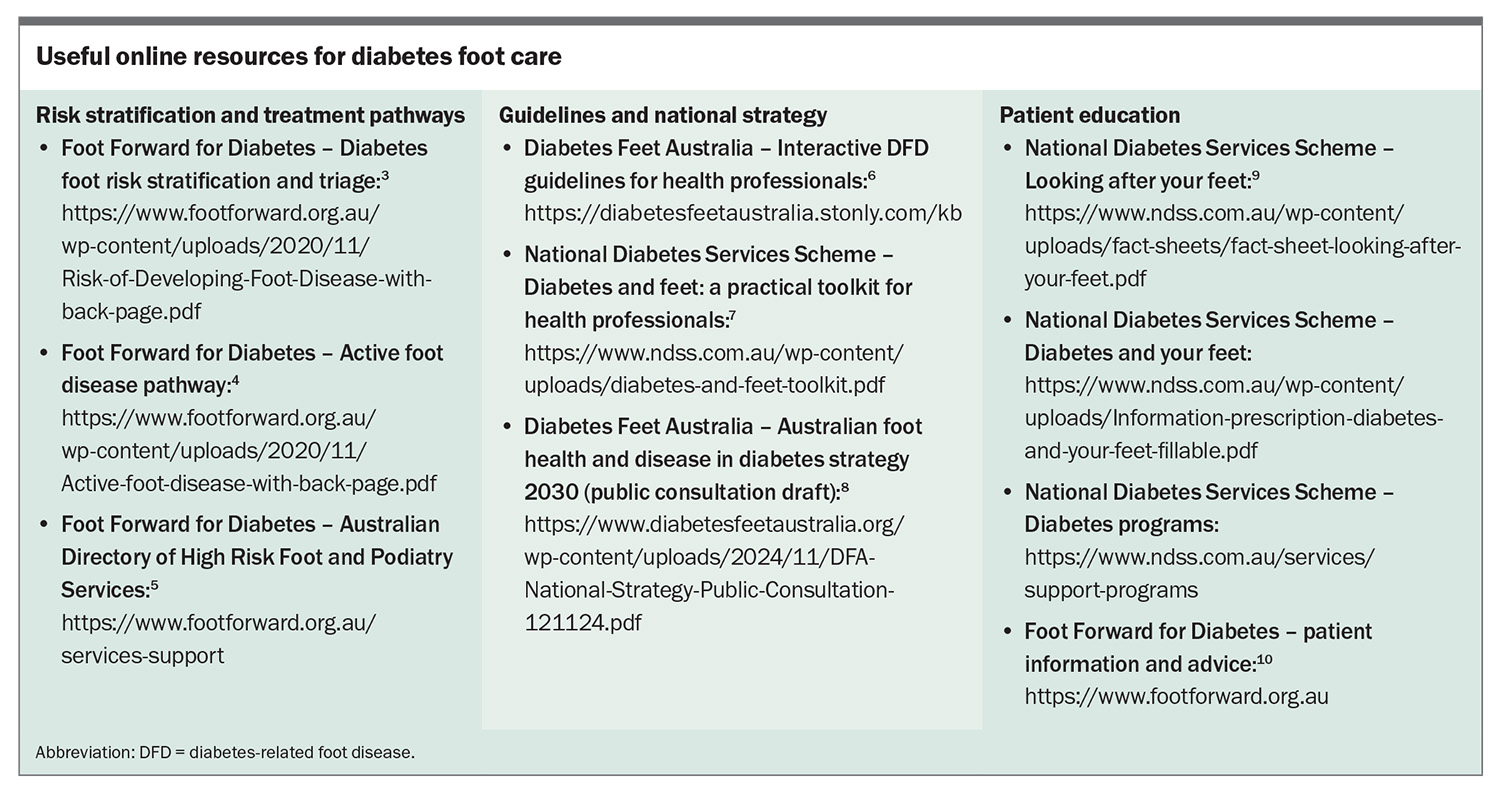

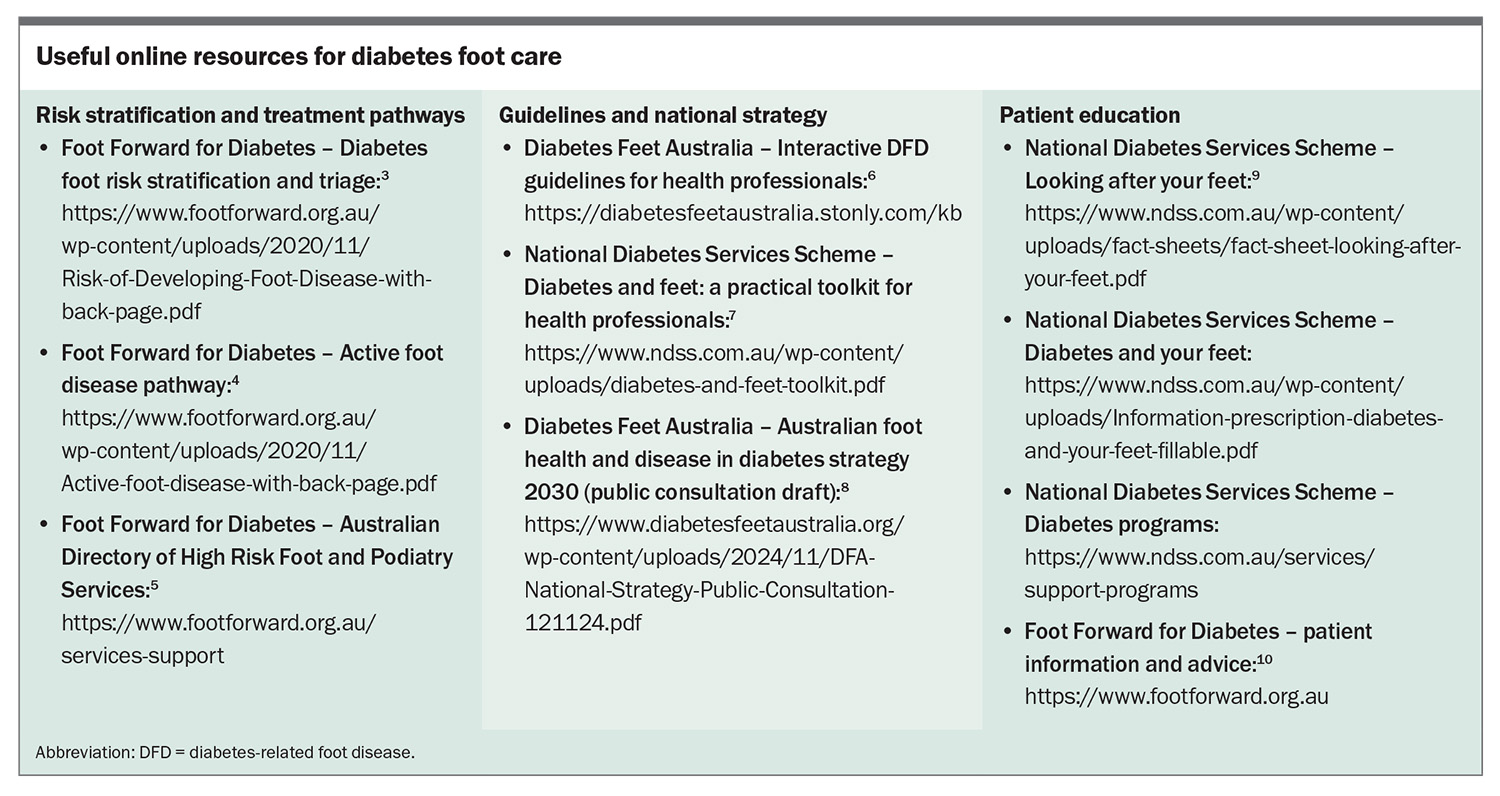

Diabetes is the fastest growing chronic condition in Australia, affecting 1.9 million people.1 People with diabetes are at risk of diabetes-related foot disease (DFD), which includes peripheral neuropathy, peripheral artery disease (PAD), infection, ulceration, neuro-osteoarthropathy, gangrene and amputation.2 Routine screening, early detection and prompt skilled management of complications can limit the associated morbidity and mortality. Education of healthcare professionals and people at risk is key to effective prevention and early intervention. Multiple Australian resources have been developed to help guide foot care for people with diabetes (Box).3-10

Why does it matter?

More than half a million people are living with DFD each year in Australia.8 Active complications, such as ulceration and Charcot foot, result in some 47,100 hospitalisations and 6300 amputations and contribute to 2500 deaths annually. Annual national healthcare costs incurred by DFD are estimated to be $2.7 billion.8

Clinicians in the primary care setting play a crucial role in foot care for people with diabetes. Foot assessment should not be neglected in the annual review of diabetes complications, noting that even active foot disease may be asymptomatic in the presence of peripheral neuropathy. Preventive practices, close monitoring and patient education, combined with appropriate escalation of care, are anticipated to reduce amputation rates by up to 85%.11 People who develop active complications benefit from close care co-ordination and, in addition to receiving expert foot care, should have review of their cardiometabolic health and psychosocial supports.

In the case of active ulceration or Charcot foot, early recognition and rapid access to specialist care at a high-risk foot service (HRFS) are major predictors of outcome. Data from the United Kingdom show the likelihood of being alive and ulceration-free at 12 weeks is 51% if specialist care is initiated within two days, compared with 36% if initiated after two months (Figure 1).12

Data from the Australian Diabetes Foot Registry suggest that the median duration of ulceration when people are first assessed by an HRFS is 31 days (interquartile range [IQR], 12–73 days), with a median outpatient waiting time after referral to an HRFS of five days (IQR, 1–12 days).13 National accreditation standards provide best-practice recommendations for HRFSs, including stringent targets to minimise waiting times.14 The typical duration of active Charcot foot at first HRFS assessment is 37 days (IQR, 17–101 days), which is particularly concerning given the urgency of this condition.15

Risk stratification for ulceration

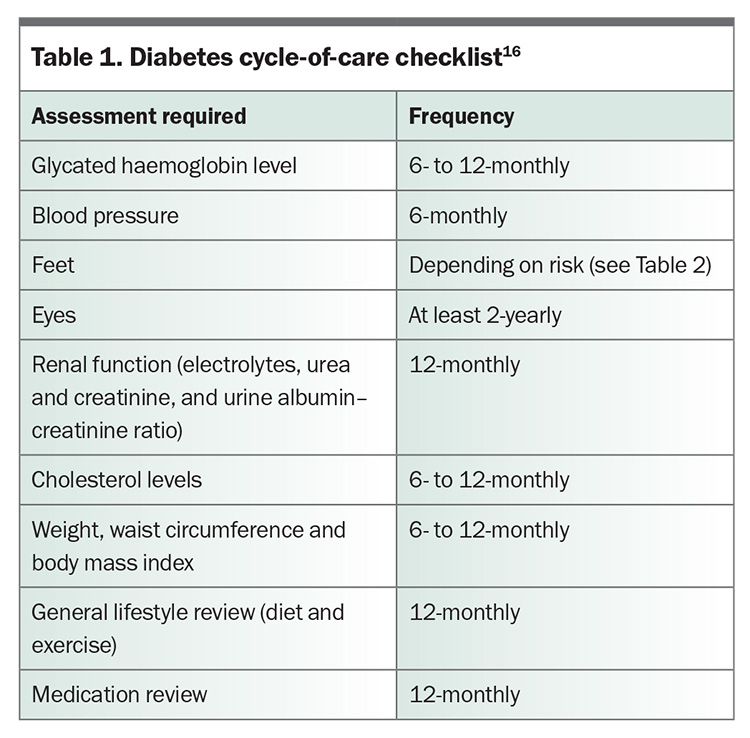

The annual diabetes cycle of care includes multiple components (Table 1), one of which is regular foot assessment.16 Foot assessment can be performed by any trained clinician; however, more thorough examination and management are achieved by involving a podiatrist in this aspect of care. The Foot Forward for Diabetes program provides an easy-reference Diabetes Foot Risk Stratification and Triage pathway and free e-learning modules for healthcare professionals.3,17

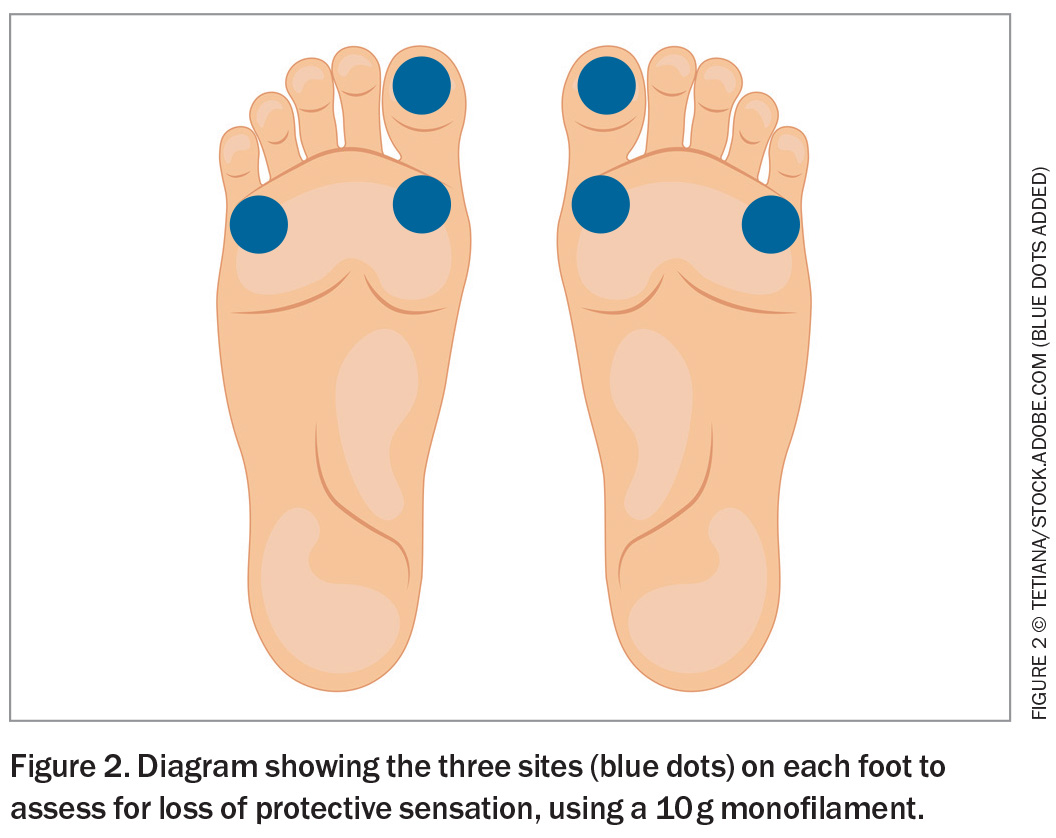

A diabetes foot assessment includes screening for loss of protective sensation and PAD. To assess the former, a standardised 10 g monofilament is briefly applied to three specific sites on each foot (avoiding any callus), until it buckles (Figure 2). With eyes closed, the patient is asked to indicate when and where the pressure is felt. Inaccurate indication for any site on repeated testing is considered loss of protective sensation. PAD may be present if either the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial pulse is not palpable.

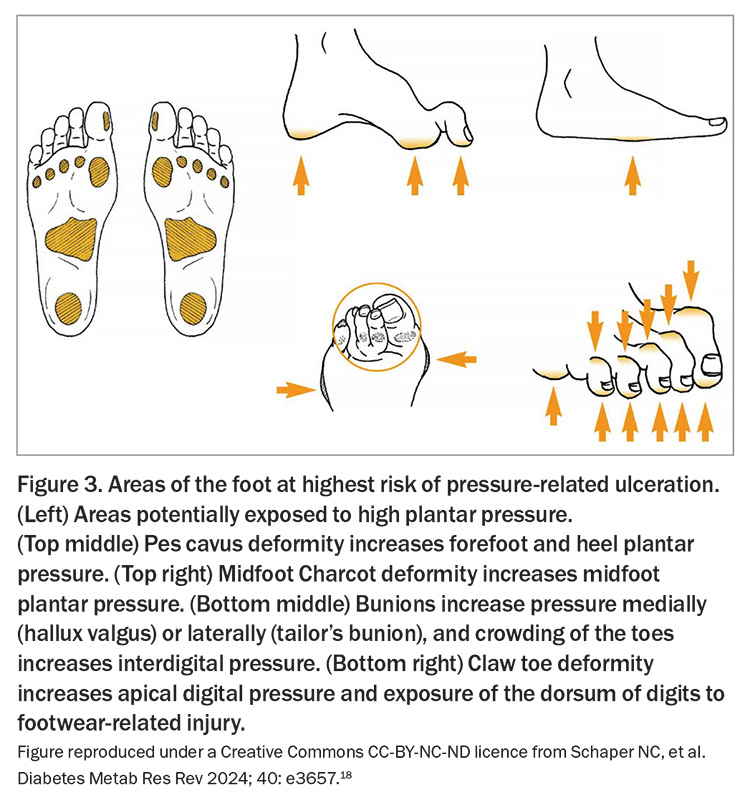

Foot assessment should also involve thorough inspection of the skin, interdigital spaces and nails, with any deformity or previous amputation noted, and identification of active ulceration or inflammation. Figure 3 shows foot deformities that convey a high risk of ulceration.18 In addition, the appropriateness of footwear should be reviewed.

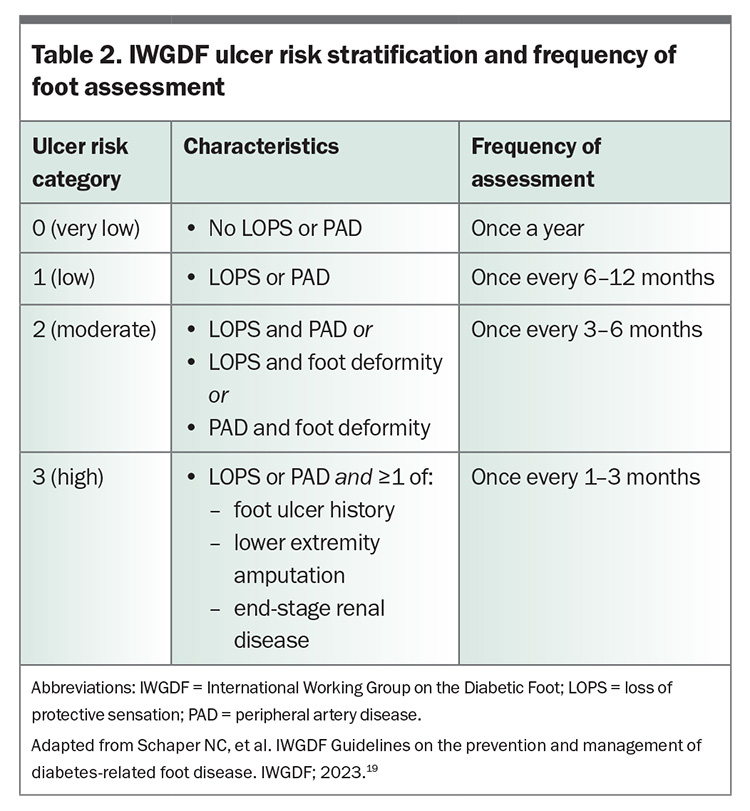

Clinical characteristics seen during the foot assessment determine risk of ulceration (Table 2), which in turn guides review frequency, prevention strategies and patient education.19 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be considered at high risk until assessed otherwise.3 For people at low to high risk of ulceration (International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot [IWGDF] categories 1–3), structured education regarding foot ulceration and its potential consequences, foot self-care, regular foot examinations and appropriate footwear is important. Foot self-care involves daily inspection and cleaning of feet, cutting nails straight across, checking footwear and ensuring the skin is well moisturised. The importance of wearing well-fitting shoes and socks and not walking barefoot should be reiterated. For people at moderate to high risk (IWGDF categories 2–3), medical-grade footwear or custom-made footwear or orthoses may be indicated, such as when foot shape or deformity is not safely accommodated in regular footwear, or to reduce plantar pressure in a previously ulcerated area.19

The level of risk also underpins treatment decisions. At-risk individuals (IWGDF categories 1–3) should be offered treatment for pre-ulcerative signs, calluses, ingrown toenails or fungal infections. In this context, referral to a podiatrist is recommended to aid preventive care, patient education and early intervention. Eligibility for publicly funded or subsidised podiatry care, such as Medicare benefits available under a Chronic Disease Management plan, My Aged Care, the National Disability Insurance Scheme and culturally safe services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, should be explored.

If any significant callus is present, orthotic interventions to reduce pressure points, particularly medical-grade footwear for people at high risk (IWGDF category 3), or digital flexor tenotomy to prevent ulceration of the digital apices, may be considered. In some cases, other orthopaedic procedures are used to reduce ulceration recurrence.20

The National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) has made available a practical toolkit for healthcare professionals, and Diabetes Feet Australia provides an interactive pathway for prevention of foot ulceration.6,7 The NDSS and the Foot Forward for Diabetes program have published reliable patient information (Box).9,10

Ulceration

Definition

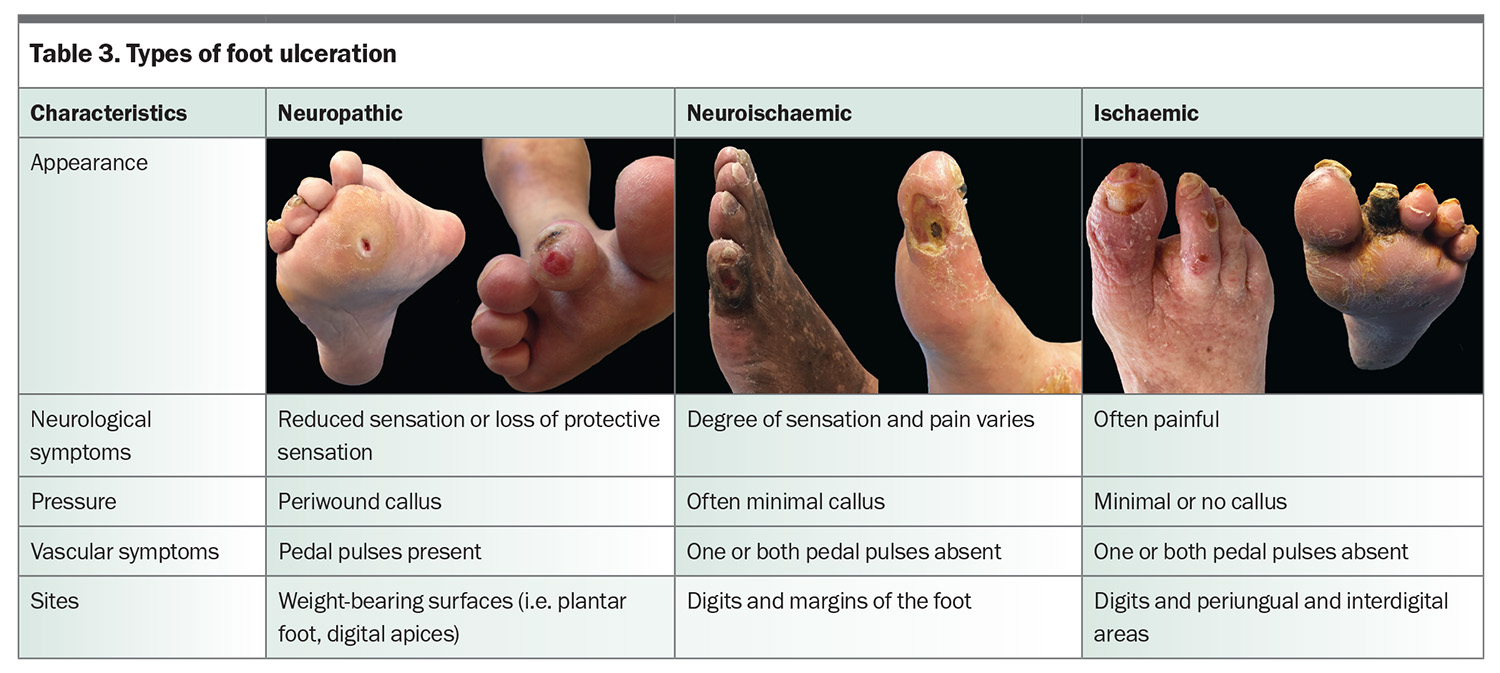

Diabetes-related foot ulceration is defined as ‘a break of the skin of the foot [i.e. distal to the malleoli] that involves as a minimum of the epidermis and part of the dermis’.2 Ulceration is typically categorised as being neuropathic, neuroischaemic or ischaemic (Table 3). Accurate clinical assessment allows the underlying aetiology to be determined and informs further care, including dressing choice, pressure offloading, referral to a vascular specialist and the need for antibiotics. Addressing precipitating and predisposing factors for ulceration can ultimately help in preventing recurrence.

Initial assessment

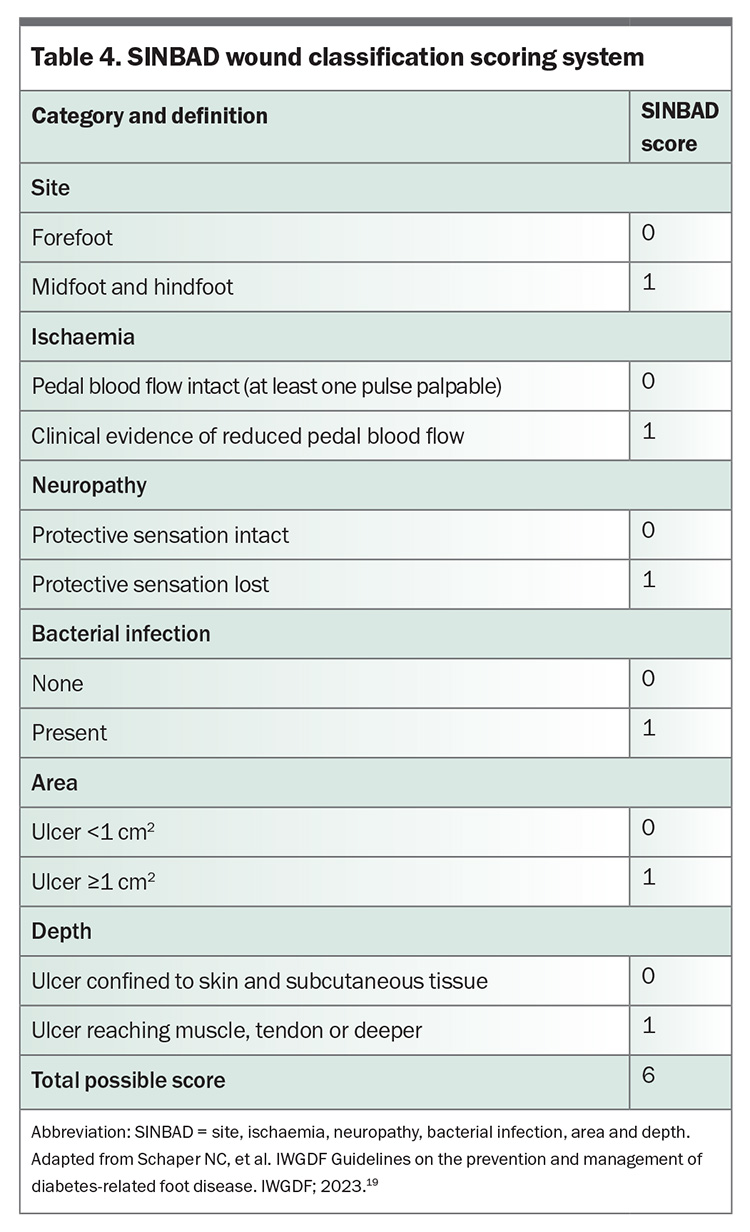

The SINBAD (site, ischaemia, neuropathy, bacterial infection, area and depth) wound classification system (Table 4) is useful for directing the clinical assessment and has prognostic implications that aid triage.21 In handover between healthcare professionals, it is important to use the individual descriptors of this system, which will guide clinical decision-making. HRFSs nationally appear to appropriately expedite review of people with severe ulceration (SINBAD score ≥3); however, healing by 12 weeks was half as likely in this group when compared with those with less severe ulceration (SINBAD score <3).13

A wound swab may be useful to guide antibiotic choice in the presence of clinical infection, but only after ulceration debridement and cleansing with saline. Chronic wounds are often colonised with multiple micro-organisms, making interpretation of results difficult.22 Accurate identification of pathogens is more likely with deep tissue culture, which is generally performed by specialist services.

Where there is clinical suspicion of osteomyelitis, the ‘probe to bone’ test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein level, and plain x-ray are recommended as initial investigations. Probing involves use of a blunt sterile instrument to gently palpate the ulceration base and allows for detection of sinuses and communication with deeper structures (e.g. hard or gritty bone). An ESR of greater than 70 mm/h (with no other clear cause) is concerning for osteomyelitis and should prompt further investigation.22

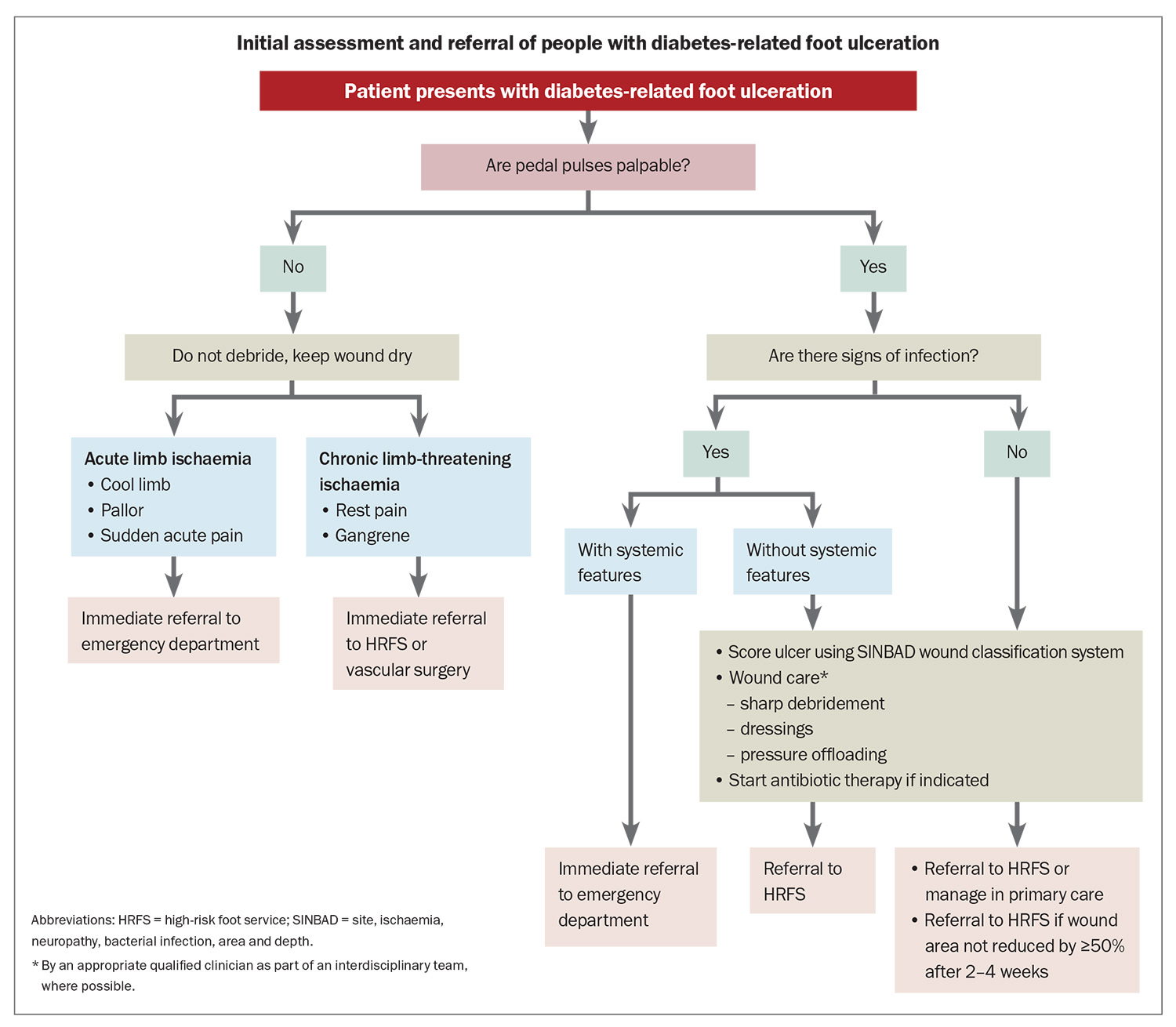

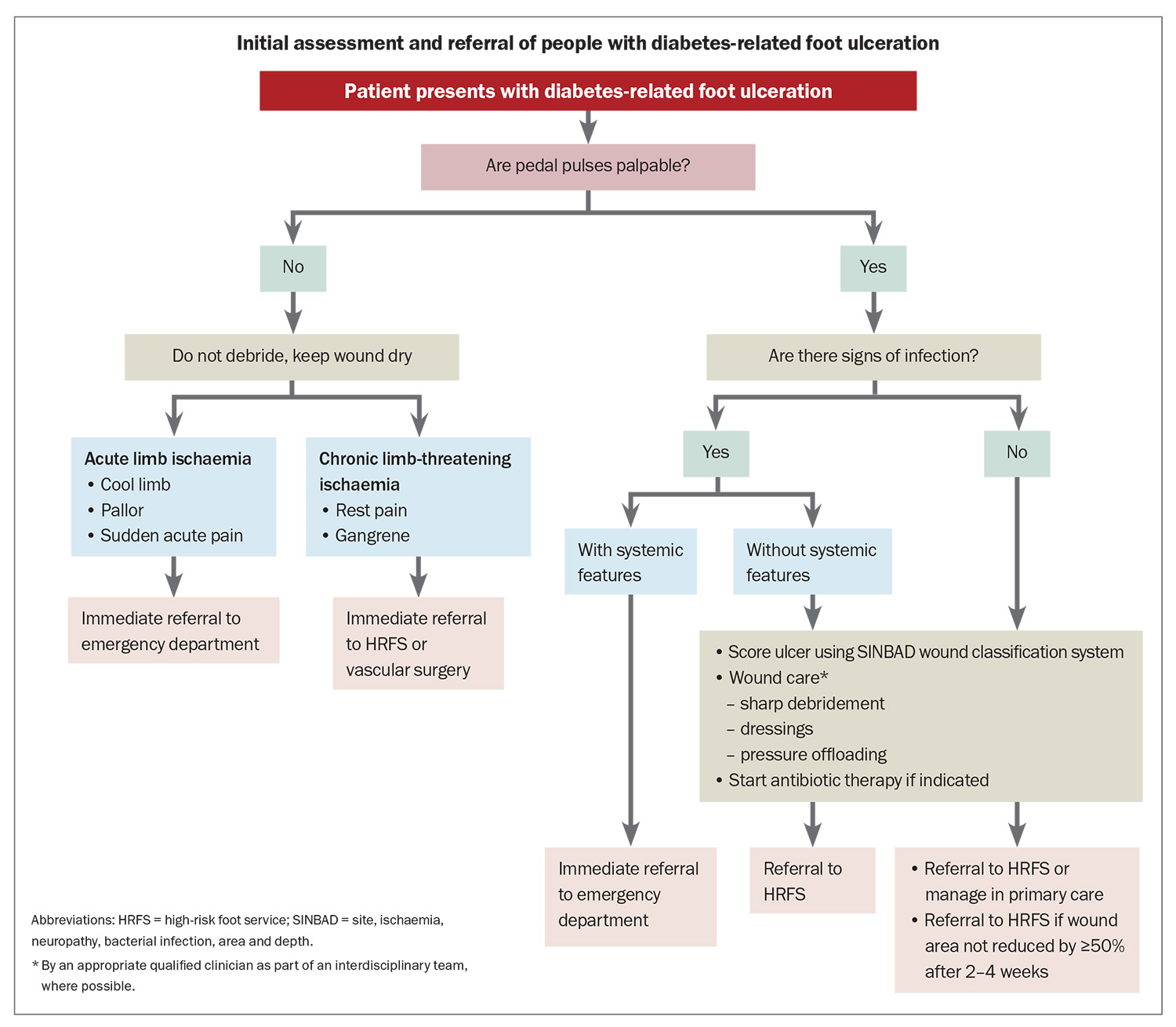

Basic management and referral processes

Initial steps in management and appropriate referral pathways are shown in the Flowchart. Immediate emergency department referral is advised for people with acute limb ischaemia or severe foot infection (i.e. associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome).4 Features of acute limb ischaemia include sudden onset of foot pain, pallor and cold limb temperature without palpable peripheral pulses. Same-day vascular surgery referral is advised for people with chronic limb-threatening ischaemia, including rest pain, gangrene and ischaemic ulceration, and may be facilitated by some HRFSs.

Mild-to-moderate infection (i.e. local signs without systemic inflammatory response syndrome) or deep ulceration warrants same-day referral to an HRFS, and empirical antibiotic therapy should be considered.4,23 Empirical antibiotic therapy typically targets Gram-positive aerobic organisms, although broader cover may be warranted for chronic infection or in people with recent antibiotic exposure. Antibiotic susceptibility of likely or proven pathogens on wound cultures guides ongoing therapy.23

In someone without PAD, superficial ulceration with no evidence of infection may be closely managed in the community. However, if there is less than a 50% reduction in wound area by two to four weeks, then referral to an HRFS is recommended (Flowchart).4 PAD is unlikely if pedal pulses are palpable; however, the presence of pedal pulses does not guarantee sufficient perfusion for healing. Podiatrists often measure toe pressures and use Doppler waveform analysis to assess adequacy of arterial flow. Clinical suspicion of PAD or delayed healing should prompt early referral for arterial studies or vascular consultation, which can also be facilitated by an HRFS.

Key principles of wound care are debridement, dressings and pressure offloading. Arterial sufficiency must be ensured before sharp wound debridement is used to remove callus or dead tissue.2,4 Dressing choice depends on the amount of exudate and presence of ischaemia; however, a nonocclusive foam dressing is generally safe to use in the short term. Pressure offloading describes strategies and devices that are used to minimise wound pressure when at rest and during mobilisation. If not protected from recurrent trauma, most wounds will not heal, and people with impaired foot sensation may not experience pain as a warning signal of ongoing injury. Optimal offloading requires skilled assessment, education and consideration of wound and patient factors. Ideally, an interdisciplinary approach involving a podiatrist and a wound nurse or an HRFS is used.

The Foot Forward for Diabetes program has a pathway summarising referral recommendations for people with active foot disease and provides a directory for locating high-risk foot and podiatry services in the local area (Box).4,5

Active Charcot foot

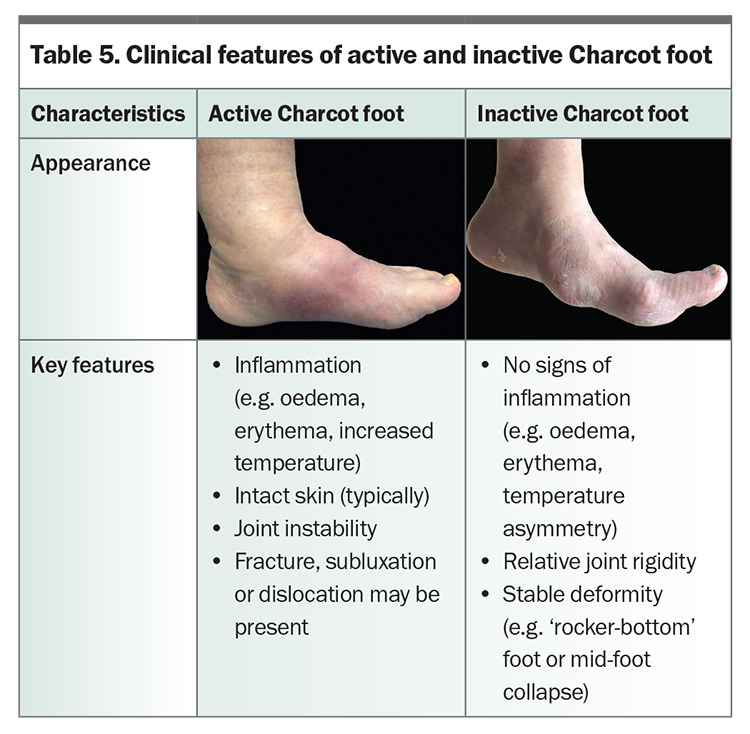

Charcot foot, or Charcot neuro-osteoarthropathy, is an inflammatory condition that occurs in the neuropathic foot or ankle, causing bone, joint and soft tissue injury.24 Resulting deformity increases the risk of ulceration, infection and amputation. It is estimated to affect 0.5 to 1% of individuals with diabetes.25,26 In the ‘active’ phase, clinical features of inflammation are present, whereas the ‘inactive’ Charcot foot may be deformed without signs of inflammation (Table 5).

Early recognition of active Charcot foot is crucial, so that immobilisation and pressure offloading can be initiated and progression of deformity minimised. Diagnosis is largely clinical, supported by radiological findings. Typical presentation includes oedema, erythema and increased temperature when compared with the contralateral foot, and the skin is often intact.24 Two-thirds of people describe discomfort or pain in the setting of neuropathy, and only one-third recall a temporally associated foot injury.27 When pain is present, it may be disproportionately less than expected based on the extent of injury, and continued walking contributes to further underlying bone destruction and deformity.

Suspected active Charcot foot requires immediate knee-high immobilisation (e.g. with a controlled ankle motion boot) while same-day urgent referral to an HRFS or other appropriately experienced and equipped service is arranged. If there are no expert services in the area, immediate emergency department attendance should be advised.5 Further investigation and management of active Charcot foot are the role of an HRFS or a specialist service; however, awareness of these principles can help referrers inform their patients.

Bilateral weight-bearing x-rays of the foot and ankle, including anteroposterior, oblique and lateral projections, are useful. If these are normal, more sensitive advanced imaging modalities, ideally MRI, should be pursued. Pathology can assist with exclusion of differential diagnoses, such as gout, cellulitis and deep vein thrombosis, but should not be used to diagnose or exclude active Charcot foot.24

Total contact casting is the gold-standard offloading approach and, when compared with removable devices, has been associated with expedited remission.28 If total contact casting is unavailable or contraindicated, some people can be managed in a knee-high device, which is preferably rendered nonremovable. Ankle-high offloading devices (e.g. Darco shoes) are insufficient.24

Accessible and equitable care

Equitable access to best-practice diabetes foot care across Australia, including accessibility of interdisciplinary HRFSs, is a significant issue. Improving outcomes for priority populations and those who are geographically isolated is a national priority.8

Examples of innovative models for equitable access to care continue to emerge; however, more widespread implementation is limited by funding. Queensland Health has led the way for overcoming geographic barriers by using telehealth, videoconferencing and specialist hub models to strengthen access to care and connect nonmetropolitan healthcare providers with specialist interdisciplinary teams.29,30 A goal of this model is upskilling rural and remote healthcare providers to create a sustainable hands-on model of care locally.29,30 New South Wales Health has invested in having at least one HRFS in each local health district, achieving a doubling of specialist foot services and a dramatic increase in outpatient care access over four years.31,32 In addition to reducing major amputation rates, this program sought to improve patient experience and empowerment.33

Mobile, flexible and culturally sensitive services also have the potential to overcome many care barriers experienced by priority populations, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and those experiencing homelessness.34,35 Culturally and linguistically diverse populations face unique challenges in accessing care, and cultural safety of services and availability of interpreters are important considerations.

Holistic care

Diabetes-related foot complications are a localised manifestation of a multiorgan disease. The five-year mortality rate for people with an active foot complication is about 30%, and closer to 50% after amputation.36 This is primarily driven by cardiovascular events, and effective management of diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors is therefore critical. An individualised approach to risk assessment and management is key. Safe glycaemic control, blood pressure and lipid targets, body weight and smoking cessation should be particularly considered.37 Where cardiovascular disease, including PAD, is established, the addition of a single antiplatelet agent to a patient’s treatment should be considered.16

Newer pharmacological agents, including sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonists, have shown renal and cardiovascular benefits that are independent of glycaemic control.38,39 The Australian Type 2 Diabetes Glycaemic Management Algorithm lists these therapies as second line, noting concurrent use is not supported by the PBS.40 Importantly, the association of canagliflozin use with amputation seen in early clinical trials has not been reproduced in studies of currently available SGLT-2 inhibitors.41,42

The psychosocial impact of DFD cannot be underestimated and has implications for patient engagement with foot care and outcomes. Ulceration and amputation have been associated with reduced quality of life, impaired physical function, financial and emotional stress, loss of employment, mood disorders and social isolation.43 Likewise, active Charcot foot is associated with marked limitations in function and societal role through its impacts on physical and mental health.27 Proactive mental health assessment, support and allied health involvement may help to reduce these sequelae of DFD.43

Conclusion

DFD carries significant morbidity and mortality. Frequent foot assessment, preventive measures, prompt management and early referral to specialist services can improve patient outcomes. Educating people with diabetes, particularly those at risk of complications, about DFD empowers them to self-care and seek timely advice. Holistic care, including management of cardiovascular risk factors and psychosocial aspects, is important. Disparity in access to specialised care is well recognised and is an area for ongoing improvement. Many Australian resources have been developed to support and educate clinicians and people living with DFD. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Islam SM, Siopis G, Sood S, et al. The burden of type 2 diabetes in Australia during the period 1990–2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2023; 199: 110631.

2. Van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, et al. Definitions and criteria for diabetes-related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024; 40: e3654.

3. Foot Forward for Diabetes. Integrated diabetes foot care pathway: diabetes foot risk stratification and triage. Canberra: National Diabetes Services Scheme; 2020. Available online at: https://www.footforward.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Risk-of-Developing-Foot-Disease-with-back-page.pdf (accessed April 2025).

4. Foot Forward for Diabetes. Integrated diabetes foot care pathway: active foot disease pathway. Canberra: National Diabetes Services Scheme; 2020. Available online at: https://www.footforward.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Active-foot-disease-with-back-page.pdf (accessed April 2025).

5. Foot Forward for Diabetes. Australian directory of high risk foot and podiatry services. Canberra: National Diabetes Services Scheme; 2025. Available online at: https://www.footforward.org.au/services-support (accessed April 2025).

6. Diabetes Feet Australia. Prevention interactive pathway. In: Interactive DFD guidelines for health professionals using the 2021 Australian guidelines for diabetes-related foot disease. Brisbane: Diabetes Feet Australia; 2021. Available online at: https://diabetesfeetaustralia.stonly.com/kb/guide/en/prevention-interactive-pathway-xDFlakvpui/Steps/1889845 (accessed April 2025).

7. National Diabetes Services Scheme. Diabetes and feet: a practical toolkit for health professionals using the Australian diabetes-related foot disease guidelines. Canberra: NDSS; 2022. Available online at: https://www.ndss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/diabetes-and-feet-toolkit.pdf (accessed April 2025).

8. Perrin BM, Hamilton EJ, Chuter V, et al. Australian foot health and disease in diabetes strategy 2030: improving the foot health of people living with diabetes. Public consultation draft. Brisbane: Diabetes Feet Australia; 2024. Available online at: https://www.diabetesfeetaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/DFA-National-Strategy-Public-Consultation-121124.pdf (accessed April 2025).

9. National Diabetes Services Scheme. Looking after your feet [fact sheet]. Canberra: NDSS; 2021. Available online at: https://www.ndss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-looking-after-your-feet.pdf (accessed April 2025).

10. Foot Forward for Diabetes. The Foot Forward program. Canberra: National Diabetes Services Scheme; 2025. Available online at: https://www.footforward.org.au/ (accessed April 2025).

11. International Diabetes Federation. Time to act: diabetes and foot care. Brussels: IDF; 2005.

12. National Health Service England. National Diabetes Foot Care Audit 2018 to 2023: key findings and recommendations. Leeds: NHS England; 2024. Available online at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-diabetes-footcare-audit/2018-2023/key-findings-and-recommendations (accessed April 2025).

13. Lasschuit JWJ. Australian Diabetes Foot Registry: inception to insight. In: Proceedings of the Lower Extremity Amputation Prevention 2024 Conference; 2024 Oct 25-26; Melbourne, Australia.

14. National Association of Diabetes Centres, National Diabetes Services Scheme, Australian Diabetes Society. NADC Collaborative interdisciplinary diabetes high risk foot services (iHRFS) standards review, version 2.0. Sydney: NADC; 2018. Available online at: https://nadc.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/iHRFSStandardsVersion2.0_2021.pdf (accessed April 2025).

15. Lasschuit JWJ. Medical management of Charcot foot. In: Proceedings of the Lower Extremity Amputation Prevention 2024 Conference; 2024 Oct 25-26; Melbourne, Australia.

16. Diabetes Australia. Screening for diabetes complications. Canberra: Diabetes Australia; 2022. Available online at: https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/blog/screening-for-diabetes-complications/ (accessed April 2025).

17. Foot Forward for Diabetes. The Foot Forward program: for healthcare professionals. Canberra: National Diabetes Services Scheme; 2025. Available online at: https://www.footforward.org.au/for-health-professionals (accessed April 2025).

18. Schaper NC, van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J, et al; IWGDF Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024; 40: e3657.

19. Schaper NC, van Netten JJ, Apelqvist J, et al; IWGDF Editorial Board. IWGDF Guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot disease. IWGDF; 2023. Available online at: https://iwgdfguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/IWGDF-Guidelines-2023.pdf (accessed April 2025).

20. Lazzarini PA, Raspovic A, Prentice J, et al; Australian Diabetes-related Foot Disease Guidelines & Pathways Project. 2021 Australian evidence-based guidelines for diabetes-related foot disease, version 1.0. Brisbane: Diabetes Feet Australia, Australian Diabetes Society; 2021. Available online at: https://www.diabetesfeetaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Australian-guidelines-for-diabetes-related-foot-disease-V1.0191021.pdf (accessed April 2025).

21. Monteiro‐Soares M, Russell D, Boyko EJ, et al; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Guidelines on the classification of diabetic foot ulcers (IWGDF 2019). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36: e3273.

22. Senneville É, Albalawi Z, van Asten SA, et al. IWGDF/IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes‐related foot infections (IWGDF/IDSA 2023). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024; 40: e3687.

23. Therapeutic Guidelines. Infections of diabetes-related foot ulcers. In: Antibiotic. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2025. Available online at: https://app.tg.org.au/viewTopic?etgAccess=true&guidelinePage=Antibiotic&topicfile=c_ABG_Infections-of-diabetes-related-foot-infections_topic_1 (accessed April 2025).

24. Wukich DK, Schaper NC, Gooday C, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of active Charcot neuro-osteoarthropathy in persons with diabetes mellitus (IWGDF 2023). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024; 40: e3646.

25. Tsatsaris G, Ekberg NR, Fall T, Catrina S. Prevalence of Charcot foot in subjects with diabetes: a nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Care 2023; 46: e217-e218.

26. Wukich DK, Frykberg RG, Kavarthapu V. Charcot neuroarthropathy in persons with diabetes: it’s time for a paradigm shift in our thinking. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024; 40: e3754.

27. Lasschuit JW, Center JR, Greenfield JR, Tonks KT; Charcot Foot Quantitative Ultrasound and Denosumab Study (CRUSADES) Investigators. Effect of denosumab on inflammation and bone health in active Charcot foot: a phase II randomised controlled trial. J Diabetes Complications 2024; 38: 108718.

28. Game FL, Catlow R, Jones GR, et al. Audit of acute Charcot’s disease in the UK: the CDUK study. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 32-35.

29. Clinical Excellence Queensland. Ambulatory high risk foot services. Brisbane: Queensland Health; 2023. Available online at: https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/improvement-exchange/ambulatory-high-risk-foot-services (accessed April 2025).

30. Clinical Excellence Queensland. Community foot care hubs. Brisbane: Queensland Health; 2024. Available online at: https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/improvement-exchange/community-foot-care-hubs (accessed April 2025).

31. Agency for Clinical Innovation. High risk foot service directory. Sydney: NSW Government; 2023. Available online at: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/networks/diabetes-and-endocrine/resources/high-risk-foot-services) (accessed April 2025).

32. Inquiry into the prevention, diagnosis and management of all forms of diabetes, and obesity, and its effects on the Australian population: NSW Health submission. Sydney: NSW Health; 2023.

33. Koff E, Lyons N. Implementing value-based health care at scale: the NSW experience. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 104-106.

34. Murray AR, Chu AFY, Lasschuit JWJ. Addressing inequalities in foot screening and care for vulnerable populations with diabetes. In: Proceedings of the Australasian Diabetes Congress 2024; 2024 Aug 21-23; Perth, Australia.

35. Barwell A (director). The problem with modern life. Season 1, episode 1 of: The hospital: in the deep end. SBS; 2024. Available online at: https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/tv-series/the-hospital-in-the-deep-end (accessed April 2025).

36. Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res 2020; 13: 16.

37. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Management of type 2 diabetes: a handbook for general practice. Melbourne: RACGP; 2024.

38. McGuire DK, Shih WJ, Cosentino F, et al. Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol 2021; 6: 148-158.

39. Giugliano D, Scappaticcio L, Longo M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and cardiorenal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an updated meta-analysis of eight CVOTs. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021; 20: 189.

40. Australian Diabetes Society. Australian type 2 diabetes glycaemic management algorithm. Sydney: ADS; 2024. Available online at: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/guideline/australian-t2d-glycaemic-management-algorithm-june-2024 (accessed April 2025).

41. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 644-657.

42. Katsiki N, Dimitriadis G, Hahalis G, et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) use and risk of amputation: an expert panel overview of the evidence. Metabolism 2019; 96: 92-100.

43. Crocker RM, Palmer KN, Marrero DG, Tan TW. Patient perspectives on the physical, psycho-social, and financial impacts of diabetic foot ulceration and amputation. J Diabetes Complications 2021; 35: 107960.