Nonsurgical treatment of thyroid nodules – the rise of thyroid ablation

There has been an exponential rise in the worldwide use of thyroid ablation techniques to treat thyroid nodules in the past decade. These techniques allow patients to avoid the thyroid hormone replacement therapy required after surgical removal and are performed under local anaesthesia in an outpatient setting. Increased awareness of these procedures by GPs will facilitate discussions with patients and optimise referrals to appropriate specialists.

- Thyroid ablation refers to the use of chemicals (ethanol ablation) or heat (thermal ablation) to shrink symptomatic thyroid nodules and is an alternative to surgical removal.

- Thyroid ablation is performed in a specialist consulting room or outpatient clinic under local anaesthesia.

- Radiofrequency ablation is the most common form of thermal ablation worldwide.

- Nodules shrink gradually over 12 to 24 months after ablation and volume reductions of 70 to 90% are generally achieved by experienced proceduralists.

- Patients often view thyroid ablation as the ‘only’ treatment option for them, but other treatments may give better results.

- GPs play an essential role in referring patients to an appropriate thyroid specialist (endocrinologist or thyroid surgeon) who can provide the detailed counselling and discussion necessary to determine whether thyroid ablation is a good option for them.

The reported prevalence of thyroid nodules varies but is estimated to be between 33 and 68% of the general population based on autopsy and ultrasound screening series.1-3 Many thyroid nodules are diagnosed incidentally on scans for other indications (e.g. CT, MRI and carotid vascular examinations) and require no active management.4 However, some nodules may slowly enlarge over time and start to compress the surrounding neck viscera, causing the patient to become symptomatic (Figure 1). Patients may present with dyspnoea, dysphagia, dysphonia, globus sensation and cosmetic concern.5

In the past, the only treatment option for benign symptomatic thyroid nodules was surgery. However, over the last decade, thyroid ablation has gained momentum worldwide as a valid and effective nonsurgical treatment option for benign nodular disease that is endorsed and supported by all major international thyroid associations and societies.4-7 Many patients prefer ablation to surgery as it preserves normal thyroid tissue and thyroid hormone replacement therapy is not required post-treatment. However, although patients may view ablation as the only option for them, careful patient selection for these treatments is vital to optimise safety and postprocedural outcomes. GPs have an essential role to play in this process, and this will be discussed in this article.

Thyroid ablation

What is thyroid ablation?

Thyroid ablation refers to the use of heat (thermal ablation) or chemicals (usually ethanol) to treat thyroid nodules and cysts. Ethanol ablation has been used for decades and is generally considered a first-line treatment option for simple thyroid cysts.4-7,8 The fluid within a cyst is aspirated out under ultrasound guidance and pure dehydrated ethanol is carefully instilled into the cyst cavity. Ethanol is generally well tolerated and very effective for appropriately chosen patients. However, once a thyroid cyst has a greater than 20% solid component (a ‘complex’ cyst), ethanol ablation becomes less effective as a treatment option and thermal ablation becomes preferable.

Thermal ablation was introduced in Australia in 2021, and increasing numbers of patients are turning to this approach for the treatment of symptomatic benign thyroid nodules. All thermal ablation techniques cause tissue coagulative necrosis by raising the cell temperature to above 50 to 60 °C. The various thermal techniques are differentiated by their method of generating heat.4,6,8,9 Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is the most commonly used type of thermal ablation worldwide and, contrary to its name, is not associated with radiation exposure. This article will focus on RFA, which is currently the only form of thermal ablation available in Australia.

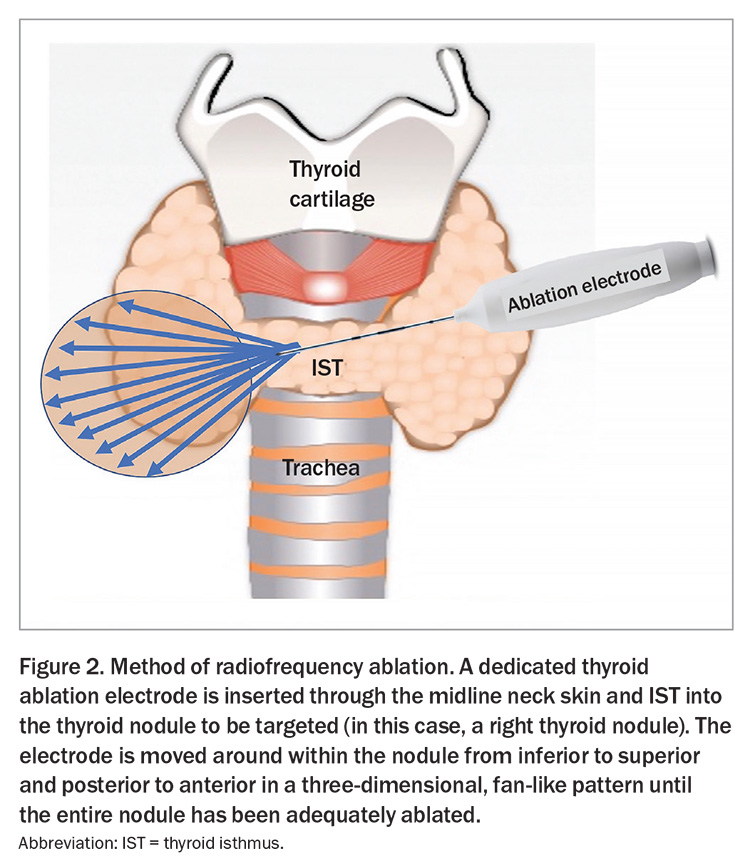

RFA is performed under local anaesthesia in a specialist consulting room or outpatient clinic. The use of sedation or general anaesthesia is relatively contraindicated from a safety perspective as these can mask patient reporting of symptoms of potential complications and lead to an increased risk of complications.4 During RFA, an 18-gauge electrode is inserted through the skin into the nodule, under ultrasound guidance. The method of RFA is illustrated in Figure 2. Ablation generally takes between 30 and 90 minutes; it varies based on the baseline size of the nodule(s) being ablated. More than one nodule can be ablated in the same setting depending on the size of the individual nodules. Although there is no ‘cut off’ maximal size for ablation, larger nodules that are greater than 4 to 6 cm will usually need more than one session of ablation to achieve sustained volume reduction. The preprocedural counselling process should highlight this and potentially encourage surgical intervention as an alternative option.

Patient selection and counselling

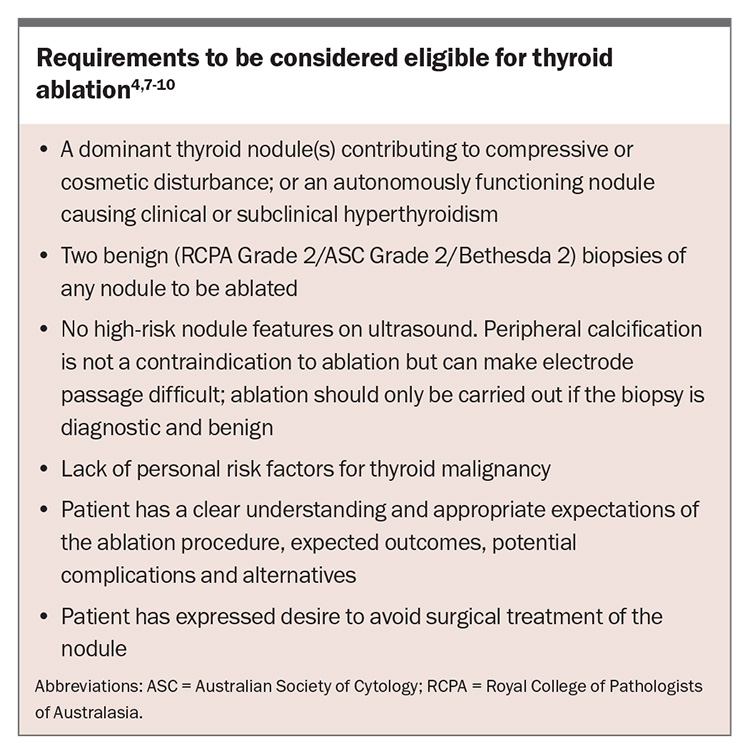

Selecting the right patients for ablation (Box) and setting realistic expectations about possible procedural outcomes are paramount to achieving reliable and safe outcomes with high patient satisfaction.

Pregnancy and cardiac implants are contraindications to ablation using monopolar electrodes; however, bipolar electrodes can be used in individuals with these contraindications. Uncontrolled coagulopathy is a contraindication to ablation.

Although a high percentage of the population will have thyroid nodules in their lifetime, ablation should only be considered for symptomatic thyroid nodules, and not for small, asymptomatic, incidentally diagnosed nodules. A thorough examination of patients’ motivations for wishing to undergo ablation is key to helping them set realistic expectations. Patients often decide on ablation as the only treatment option they would consider for their individual disease. It is crucial that every patient undergoes intensive preprocedural assessment and counselling that explores all treatment options available, including observation, surgery, ablation and radioactive iodine (if appropriate for overactive ‘toxic’ nodular disease).

This counselling process helps clarify patient desires and expectations, and determines which treatment modality is the safest and most effective and will best meet patients’ expectations. Although many thyroid nodules could technically be treated using ablation, other treatment methods are often more appropriate because of factors such as massive size, retrosternal extension, proximity to critical nerves and blood vessels or classification as a diffuse multinodular disease subtype. It is important that such counselling is done by a thyroid specialist (endocrinologist or thyroid surgeon), as stated in most major thyroid ablation guidelines.4,7-10 If this specialist does not perform ablation themselves, they should ensure that the patient’s disease subtype is suitable for ablation and that the patient has realistic expectations and an understanding of ablation before referring to a doctor who performs the procedure.

Complications

Complications of ablation are rare when the procedure is carried out by a practitioner with extensive experience. The most common complications are superficial skin bruising and local tissue pain. Commercially available RFA electrodes are internally cooled with cold fluid throughout the procedure and, thus, the risk of skin burns is exceptionally low because only the tip of the electrode ‘actively’ produces heat. This active tip must be kept under direct ultrasound vision by the proceduralist at all times. The recurrent laryngeal nerves are at risk of heat injury during thermal ablation. As in thyroid surgery, if these nerves are damaged, the patient will have a hoarse voice after the procedure for weeks to months. The risk of temporary hoarseness after ablation is similar to the risk of hoarseness after thyroid surgery and is generally quoted as being between 2 and 5%. Permanent hoarseness from laryngeal nerve injury is very rare after ablation (<1%).4,7-11

Unlike in thyroid surgery, hypocalcaemia caused by parathyroid gland injury is not a significant risk with ablation. There have been case reports of thermal injury to other neck structures such as the trachea, oesophagus, vagus nerve and sympathetic chain; however, these risks are extremely low with an experienced specialist. All heat-related risks can be mitigated with the use of low RFA powers, careful electrode size choice and placement and extensive proceduralist experience.

Expected outcomes

After ablation, nodules shrink gradually over six to 12 months. Shrinkage starts at around 10 to 14 days after ablation and maximal rates of shrinkage generally occur within the first one to three months, with slower shrinkage thereafter. Most nodules will achieve a volume reduction from baseline of 70 to 90% after 12 to 24 months. Interestingly, although shrinkage occurs gradually over 12 months, most patients (>90%) report a resolution of their symptoms within four to eight weeks of the procedure.

Follow up of ablated nodules

The appearance of a nodule changes after ablation and the commonly used Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TIRADS) should not be used for nodules after ablation. Figure 3 demonstrates the ultrasound appearance of a nodule before and after ablation. The doctor performing the ablation has a duty of care to the patient to follow up with them for the first year after the procedure, with ultrasounds performed at one to two months, six months and 12 months postablation to ensure a smooth recovery process and appropriate nodule shrinkage. After 12 months, and if the nodule has responded well to the ablation, the patient may be referred back to their GP, usually with a plan for annual or biannual ultrasounds thereafter. For larger nodules, the risk of needing a second ablation is higher and the doctor performing the ablation may need to follow up with the patient for longer than 12 months to assess for regrowth and the need for additional ablation procedures.

Ablation versus surgery for benign thyroid nodules: the pros and cons

Pros of ablation

Most patients seek ablation to avoid the risk of needing thyroid hormone replacement therapy. After a hemithyroidectomy, there is a 20 to 40% chance that a patient may need to start thyroid hormone replacement therapy in the five years after surgery.12 With ablation, that risk is less than 1%, provided the patient does not have preprocedural hypothyroidism. Avoidance of requiring thyroid hormone replacement therapy is one of the primary advantages of ablation over surgery. However, it is important to counsel patients who have normal thyroid hormone levels but positive thyroid antibodies suggestive of Hashimoto’s disease (antithyroglobulin antibody, thyroid peroxidase) that, over time, they may require thyroid hormone replacement therapy because of the disease process.

Ablation is carried out under local anaesthesia and causes minimal tissue disruption as it targets the nodule alone and leaves surrounding thyroid and connective tissues relatively untouched. As such, there is no neck scar formation and recovery is extremely quick for most patients, generally with one to two days of mild neck tenderness and swelling.

Cons of ablation

The biggest drawback of ablation compared with surgery is that nodules can require more than one ablation over time. The risk of requiring a second procedure is higher with a larger baseline volume of the nodule, and nodules that are greater than 20 to 30 mL in volume are more likely to need repeat ablations. Ablation can be uncomfortable for some patients, particularly with larger nodules, where maximal safe local anaesthetic volumes (calculated based on patient weight) may not be enough to anaesthetise the entirety of a given nodule. Generally, the discomfort from the procedure is mild and does not prevent completion of the procedure.

Missed malignancy is another risk of ablation compared with surgery. The risk of missed malignancy is higher for larger nodules, and all patients, regardless of the size of their nodule, must have two benign biopsies of any given nodule and a low-to-intermediate risk nodule ultrasound appearance to be eligible for ablation.

Currently in Australia, there is no Medicare item number for ablation and, thus, private insurance companies usually refuse to cover the procedure, meaning that patients must pay out of pocket. However, it is hoped that a temporary Medicare number may be issued in the near future.

Ablation for nonbenign thyroid disease: papillary thyroid microcarcinoma

Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) refers to papillary thyroid cancers that are less than 1 to 1.5 cm in size. The use of thermal ablation for selected PTMCs is gaining in popularity worldwide, including in Australia. In general, there are three possible treatment options for patients with PTMC: active surveillance (‘observation’), ablation or surgery. In active surveillance, the PTMC is observed with serial ultrasounds every six months. About 8 to 10% of PTMCs under active surveillance progress over time by growing or spreading to surrounding neck lymph nodes. Progressive PTMCs such as these require treatment.13

Early series of thermal ablation for PTMCs have shown that ablation lowers the risk of disease progression noted with active surveillance from 8 to 10% to about 1 to 2%. Ablation for PTMC should only be performed by doctors who have extensive experience in benign nodule ablation as the technique for ablation of PTMC differs from that for benign disease.14-17 Only some PTMCs are eligible for ablation, and this decision is based on the location within the thyroid gland, proximity to critical structures (trachea, laryngeal nerves) and cytology. Generally, PTMCs that are not eligible for active surveillance are also not eligible for ablation.

The role of GPs in safeguarding patients

Thyroid ablation can be performed by doctors from multiple disciplines, including thyroid surgery, endocrinology and radiology. There is a significant learning curve to achieving reliable and safe outcomes with ablation, depending on baseline doctor ultrasound and biopsy experience. World guidelines on ablation recommend that radiologists who perform ablation do so as part of a multidisciplinary team where the patient is first seen and counselled by a thyroid specialist (endocrinologist or thyroid surgeon), as discussed above.4,7,9,10 These guidelines have been put in place to ensure that patients have adequate and appropriate preprocedural counselling regarding the pros and cons of all possible treatment options.

Doctors in Australia have minimal experience with ablation at the current time. However, as more doctors learn to perform these procedures, including radiologists, GPs will play an essential role in ensuring that patients are initially seen by a thyroid specialist who can provide adequate counselling. That thyroid specialist may themselves be qualified to perform ablation or, if not, they can refer the patient appropriately. Direct referral to a radiologist without initial discussion with a thyroid specialist could lead to inappropriate patient selection and overzealous use of ablation for asymptomatic incidentally detected nodules that do not require active treatment and for nodules that could be better and more safely treated using another modality. A suggested algorithm for GP assessment and referral of a patient with thyroid nodules who may desire ablation is presented in the Flowchart.

Conclusion

Thyroid ablation has gained widespread acceptance worldwide as a valid alternative to surgery for select patients with benign thyroid nodules. The avoidance of thyroid hormone replacement therapy postprocedure combined with a quick recovery makes ablation appealing to patients of all ages. In experienced hands, ablation can achieve safe, reliable outcomes with a minimal risk of complications. However, patient selection and preprocedural counselling is essential to the safe performance of these techniques and to achieving realistic outcomes. For doctors wanting to perform thyroid ablation, there is a steep learning curve regardless of subspecialty training. As more doctors in Australia start to perform these techniques, GPs will play an increasingly vital role in ensuring patients are initially referred to a thyroid specialist for an involved discussion about all available treatment options for their individual disease subtype. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Associate Professor Sinclair is Editor-in-Chief of VideoEndocrinology, New York City, NY; and Founding Executive Member of the North American Society for Interventional Thyroidology.

References

1. Mortensen JD, Woolner LB, Bennett WA. Gross and microscopic findings in clinically normal thyroid glands. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1955; 15: 1270-1280.

2. Ross DS. Nonpalpable thyroid nodules-managing an epidemic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 1938-1940.

3. Guth S, Theune U, Aberle J, et al. Very high prevalence of thyroid nodules detected by high frequency (13 MHz) ultrasound examination. Eur J Clin Invest 2009; 39: 699-706.

4. Sinclair CF, Baek JH, Hands KE, et al. General principles for the safe performance, training, and adoption of ablation techniques for benign thyroid nodules: an American Thyroid Association statement. Thyroid 2023; 33: 1150-1170.

5. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016; 26: 1-133.

6. Yogaraj V, Sinclair C, Tchernegovski A, Phyland D. The prevalence of local symptoms in benign thyroid disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2025; 135: 1553-1562.

7. Durante C, Hegedüs L, Czarniecka A, et al. 2023 European Thyroid Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for thyroid nodule management. Eur Thyroid J 2023; 12: e230067.

8. Kuo JH, Sinclair CF, Lang B, et al. A comprehensive review of interventional ablation techniques for the management of thyroid nodules and metastatic lymph nodes. Surgery 2022; 171: 920-931.

9. Kim JH, Baek JH, Lim HK, et al. Guideline Committee for the Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology (KSThR) and Korean Society of Radiology. 2017 Thyroid Radiofrequency Ablation Guideline: Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology. Korean J Radiol 2018; 19: 632-655.

10. Orloff LA, Noel JE, Stack BC Jr, et al. Radiofrequency ablation and related ultrasound-guided ablation technologies for treatment of benign and malignant thyroid disease: an international multidisciplinary consensus statement of the American Head and Neck Society Endocrine Surgery Section with the Asia Pacific Society of Thyroid Surgery, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons, European Thyroid Association, Italian Society of Endocrine Surgery Units, Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology, Latin American Thyroid Society, and Thyroid Nodules Therapies Association. Head Neck 2022; 44: 633-660.

11. Zhao ZL, Wei Y, Peng LL, Li Y, Lu NC, Yu MA. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in thermal ablation of thyroid nodules-risk factors and cause analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022; 107: e2930-e2937.

12. Barranco H, Fazendin J, Lindeman B, Chen H, Ramonell KM. Thyroid hormone replacement following lobectomy: long-term institutional analysis 15 years after surgery. Surgery 2023; 173: 189-192.

13. Sasaki T, Miyauchi A, Fujishima M, et al. Comparison of postoperative unfavorable events in patients with low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma: immediate surgery versus conversion surgery following active surveillance. Thyroid 2023; 33: 186-191.

14. Oda H, Miyauchi A, Ito Y, et al. Incidences of unfavorable events in the management of low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid by active surveillance versus immediate surgery. Thyroid 2016; 26: 150-155.

15. Valcavi R, Piana S, Bortolan GS, Lai R, Barbieri V, Negro R. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous laser ablation of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a feasibility study on three cases with pathological and immunohistochemical evaluation. Thyroid 2013; 23: 1578-1582.

16. Ma B, Wei W, Xu W, et al. Surgical confirmation of incomplete treatment for primary papillary thyroid carcinoma by percutaneous thermal ablation: a retrospective case review and literature review. Thyroid 2018; 28: 1134-1142.

17. Xu D, Ge M, Yang A, et al. Expert consensus workshop report: guidelines for thermal ablation of thyroid tumors (2019 edition). J Cancer Res Ther 2020; 16: 960-966.