Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Part of the autoimmune diabetes spectrum

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) is a slowly progressive form of autoimmune diabetes that shares clinical features of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Its clinical characteristics include the lack of requirement for insulin for at least six months from diagnosis, positivity to diabetes autoantibodies and age at diagnosis typically greater than 30 years. Referral of patients to an endocrinologist can be considered to confirm a LADA diagnosis and guide management.

- Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) has overlapping features of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, characterised by the presence of diabetes autoantibodies and lack of need for insulin for at least six months from diagnosis.

- Accurate diagnosis of LADA is essential in guiding optimal, personalised management plans.

- The need for insulin in patients with LADA can be assessed based on serial C-peptide monitoring and assessment of glycaemic control.

- Referral of patients suspected of having LADA to an endocrinologist is recommended where practicable to confirm diagnosis and guide management.

Case scenario

Tracey, a 38-year-old woman presented to your clinic with lethargy and a two-month history of polyuria, polydipsia and weight loss. She had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) three years ago. She was treated initially with lifestyle measures, but commenced oral diabetes medications two years ago. Her glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was 6.2% when she was last reviewed 12 months ago, while she was taking sitagliptin/metformin 50/1000 mg twice daily.

At presentation, there were no features suggestive of an underlying infection. She had no known diabetes-related complications and was up to date with complication screening. She had lost 3 kg in the past two months and had a current body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2. Her blood pressure was 120/75 mmHg. She had a background history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which was appropriately managed with thyroxine 75 microgram/day. Her father had been diagnosed with T2D at the age of 60 years. She had no clinical features of insulin resistance (e.g. acanthosis nigricans or skin tags).

Formal blood testing showed that Tracey’s random blood glucose level was 18 mmol/L and her HbA1c level was 11.5%. Her glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 65 autoantibodies were elevated (>2000 U/mL; reference range 0.0 to 0.9). She was commenced on pre-mixed insulin aspart (30 units/mL) and insulin aspart protamine (70 units/mL) 10 units with breakfast and dinner.

What is latent autoimmune diabetes in adults and how does it compare with other types of diabetes?

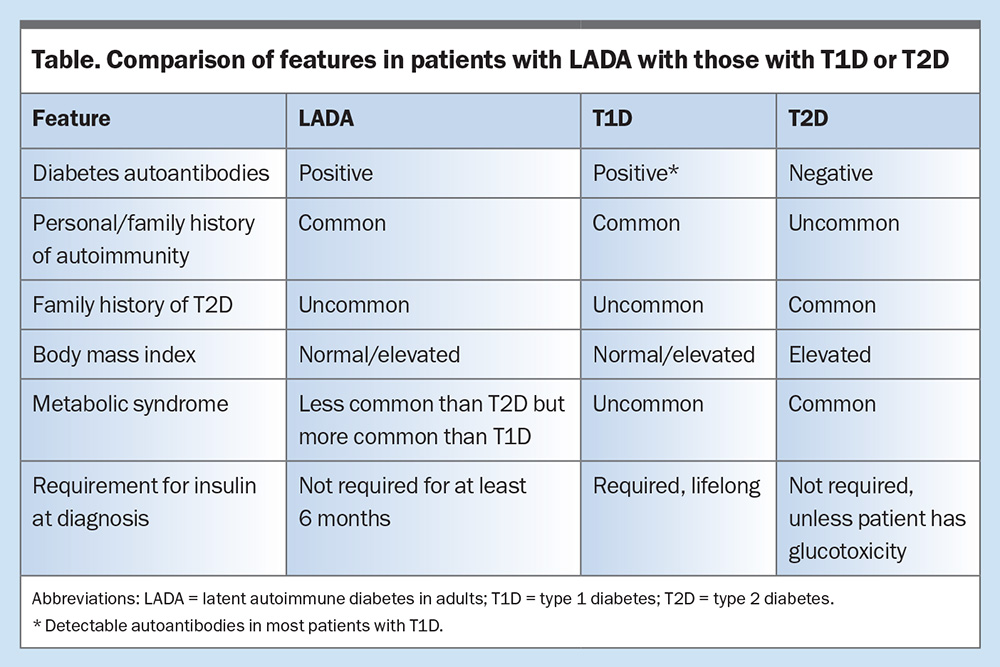

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), often termed ‘type 1.5 diabetes’ or ‘slow-burning type 1 diabetes (T1D)’, shares clinical features of T1D and T2D. It is driven by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, similar to that which occurs in T1D. The rate of decline in insulin secretory capacity in patients with LADA is slower than that in classic T1D. The prevalence of LADA among patients with T2D is 4 to 12%. At diagnosis, patients often phenotypically resemble individuals with T2D and they do not require insulin for at least six months.1,2 The latter is often an arbitrary feature, as the onset of hyperglycaemia may not always be known.

Age greater than 30 years at diagnosis has been used to distinguish patients with LADA from those with T1D. They are differentiated from patients with T2D by the presence of diabetes autoantibodies, typically GAD autoantibodies.3,4 This predisposes them to insulin deficiency, although at a much slower rate than that seen in T1D. Many patients do not require insulin for years after diagnosis, depending on the age at diagnosis, autoantibody titre and presence of multi-autoantibody positivity.2,4,5 Patients with LADA are more likely to have a personal or family history of autoimmunity, with a lower frequency of metabolic syndrome when compared with those with T2D.1,3

A comparison of features in patients with LADA with those who have T1D or T2D is summarised in the Table.

What clinical and biochemical features should raise suspicion of LADA?

LADA should be considered in patients with T2D with sudden deterioration in glycaemic control, diabetic ketoacidosis or any other atypical features, such as young age at onset, healthy or slightly overweight BMI, personal history of autoimmunity or family history of T1D.

Which investigations should be performed to screen for LADA?

GAD autoantibody testing should be performed in patients with clinical or biochemical features suspicious for LADA, as most patients will be positive for this autoantibody. If they are GAD autoantibody negative, and the index of suspicion remains high, tyrosine phosphatase (IA2) and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) autoantibodies should also be measured. Those with higher autoantibody concentrations are more likely to progress to insulin deficiency.2

Random C-peptide (with paired glucose) levels can be used as a surrogate marker for insulin secretion and guide further management. C-peptide is a peptide cleaved from proinsulin during endogenous insulin production. Measurement of C-peptide is preferred over insulin, as insulin undergoes hepatic metabolism and C-peptide laboratory assays are more reliable, with no cross-reactivity for exogenous insulin. The latest LADA management guidelines consensus statement recommends serial C-peptide monitoring to guide the need for insulin commencement.1

What is the management of patients with LADA and how does it differ from that of T1D and T2D?

Serial C-peptide monitoring may be used to guide the timing of insulin commencement. In patients with a robust random C-peptide level of greater than 0.7 nmol/L (700 pmol/L), it is recommended that LADA be managed according to T2D guidelines, including metformin treatment and weight loss (through physical activity and dietary modification) for patients with overweight and obesity.1 Referral to a dietitian and exercise physiologist should be considered. Improvement in insulin resistance may lead to a relative improvement in glycaemia due to relatively greater effectiveness of residual insulin secretion.

Patients with intermediate C-peptide levels of 0.3 to 0.7 nmol/L (300 to 700 pmol/L)can be managed with modified T2D management guidelines with serial C-peptide monitoring every six months.1 This modification involves the avoidance of sulfonylureas, which may result in a more rapid deterioration of beta-cell function.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors should be used judiciously in patients with low to intermediate C-peptide levels due to patients’ heightened risk of ketoacidosis. Patients who commence SGLT-2 inhibitors should be educated regarding blood ketone monitoring during intercurrent illness. Prescription of SGLT-2 inhibitors can be considered in patients with high cardiovascular and kidney disease risk with adequate renal function and a BMI greater than 27 kg/m2.1 Alternative therapies include the dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, which theoretically may improve insulin secretory capacity and delay the need for insulin.

Patients with C-peptide levels less than 0.3 nmol/L (300 pmol/L) be can be commenced on insulin, especially if hyperglycaemic. Use of insulin in conjunction with other therapies could be considered in those with inadequate glycaemic control despite the use of other diabetes agents (HbA1c >7%) and in individuals planning pregnancy. All patients should also be counselled about the need to seek medical attention in the event of glycaemic deterioration, for consideration of insulin treatment. Insulin pump therapy, with automated insulin delivery, is an option for people with LADA and progressive insulin deficiency.

What is the prognosis for patients with LADA?

Progression to insulin deficiency is slower in patients with LADA than in those with T1D. However, these patients are at increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis, particularly in those with a low C-peptide level. Compared with T2D, there is no difference in disease- specific cardiovascular outcomes in patients with LADA.6

What aspects of diagnosis can be facilitated in general practice?

General practitioners can facilitate the diagnosis of LADA by considering testing for diabetes autoantibodies in patients with atypical T2D features or sudden deterioration of glycaemic control.

What are the indications for specialist referral?

Diagnosis of LADA can be difficult, and it is recommended that patients with autoimmune diabetes are referred, where practicable, for specialist multidisciplinary care. Referral can also be considered in patients with T2D and atypical features or in those with sudden deterioration in glycaemic control to confirm a LADA diagnosis.

Patient progress

Tracey’s glycaemia significantly improved following the commencement of insulin. Six months later, her HbA1c was 6.5%, at which point she was keen to fall pregnant. Her sitagliptin/metformin was subsequently ceased and her pre-mixed insulin regimen was switched over to basal bolus insulin. She was seen regularly by an endocrinologist throughout her pregnancy. She delivered a healthy baby girl at term, with no macrosomia or neonatal hypoglycaemia and remained on insulin postpartum.

Conclusion

LADA is a slowly progressive form of autoimmune diabetes that shares clinical features of T1D and T2D. Its clinical characteristics include the lack of requirement for insulin for at least six months from diagnosis, positivity to one or more diabetes autoantibody, most often GAD autoantibody, and age at diagnosis in adulthood and typically greater than 30 years. Other features include the presence of a personal or family history of autoimmunity or T1D and a lower frequency of metabolic syndrome features compared with T2D.

Diagnosis can be difficult and should be considered in adults with atypical features such as ketoacidosis, autoimmune history, family history of T1D or sudden deterioration in glycaemic control. Referral of patients to an endocrinologist can be considered to confirm the diagnosis and guide management. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Patel: None. Professor Greenfield has received study drug and placebo from Novo Nordisk for a study of semaglutide in type 1 diabetes and speaker fees from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Abbott and the Limbic.

References

1. Buzzetti R, Tuomi T, Mauricio D, et al. Management of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: a consensus statement from an international expert panel. Diabetes 2020; 69: 2037-2047.

2. Liu L, Li X, Xiang Y, et al. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults with low-titer GAD antibodies: similar disease progression with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide, multicenter prospective study (LADA China Study 3). Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 16-21.

3. Tuomi T, Carlsson A, Li H, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of type 2 diabetes with and without GAD antibodies. Diabetes 1999; 48: 150-157.

4. Turner R, Stratton I, Horton V, et al. UKPDS 25: autoantibodies to islet-cell cytoplasm and glutamic acid decarboxylase for prediction of insulin requirement in type 2 diabetes. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Lancet 1997; 350: 1288-1293.

5. Hawa MI, Kolb H, Schloot N, et al. Adult-onset autoimmune diabetes in Europe is prevalent with a broad clinical phenotype: Action LADA 7. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 908-193.

6. Maddaloni E, Coleman RL, Pozzilli P, Holman RR. Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (UKPDS 85). Diabetes Obes Metab 2019; 21: 2115-2122.