Managing men with diabetes and erectile dysfunction

Men with diabetes are at higher risk of experiencing erectile dysfunction, and at a younger age. Screening for erectile dysfunction during routine diabetes consultations with men can identify those for whom this may be a problem. Men should be assessed for any underlying risk factors and contributing comorbidities. Treatments are available, and ensuring men with diabetes have good glycaemic control can also help improve erectile function.

- Diabetes is an important risk factor for erectile dysfunction.

- Men should be asked about erectile dysfunction as part of their routine diabetes consultation.

- Men presenting with erectile dysfunction should have a general health assessment and be screened for cardiovascular disease.

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors remain first-line therapy for erectile dysfunction.

- There are additional treatment options, including surgery, for men who do not respond to less-invasive therapies.

Erectile dysfunction is defined as the persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain an erection sufficient to permit satisfactory sexual intercourse.1 It is a common and often under-recognised problem. Diabetes is a known risk factor for erectile dysfunction and shares many associations with it, including vascular disease, neuropathy and depression. This article explores the association between erectile dysfunction and diabetes and the available therapies for treatment of erectile dysfunction, including specific considerations for men with diabetes.

Epidemiology

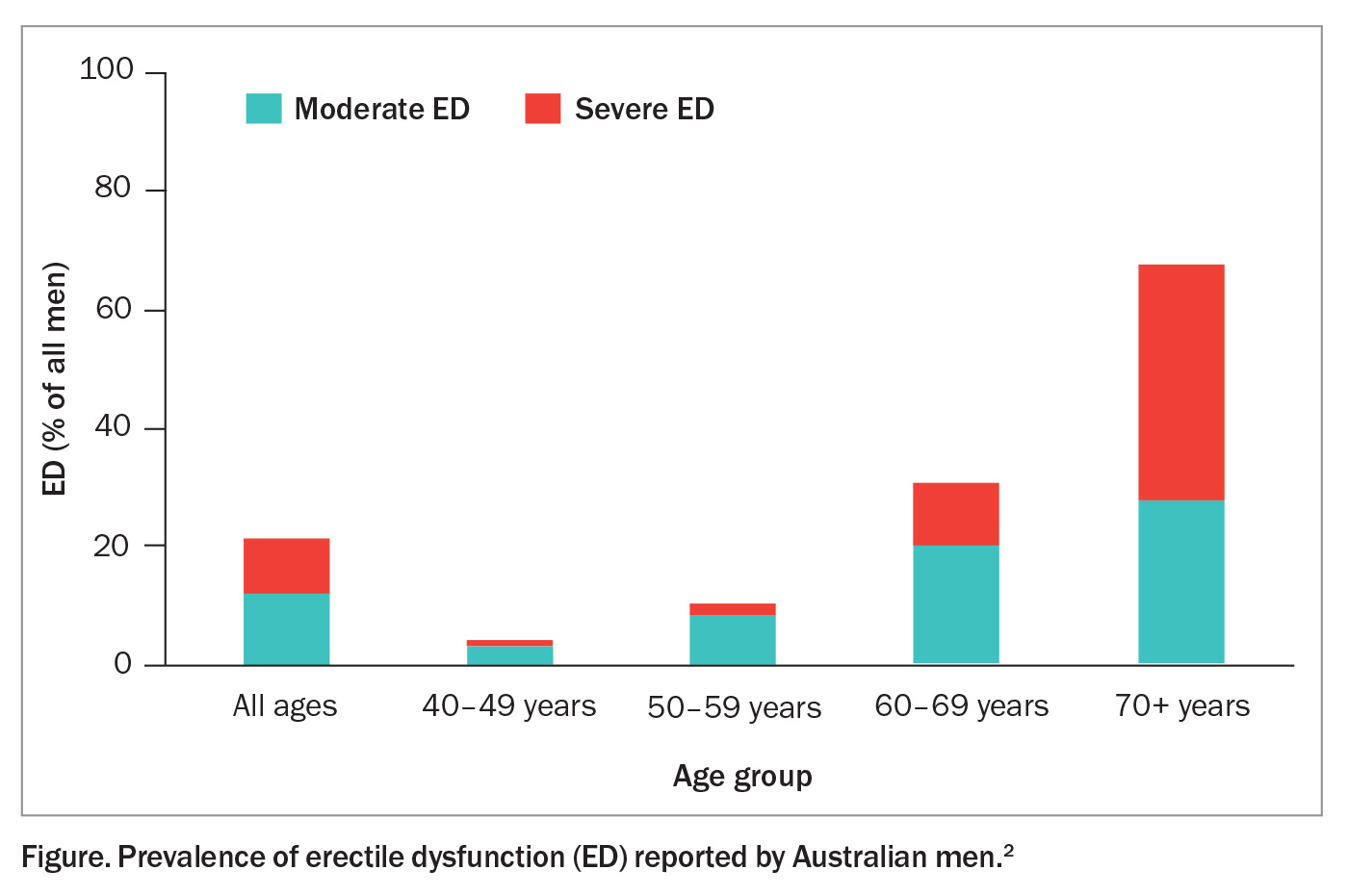

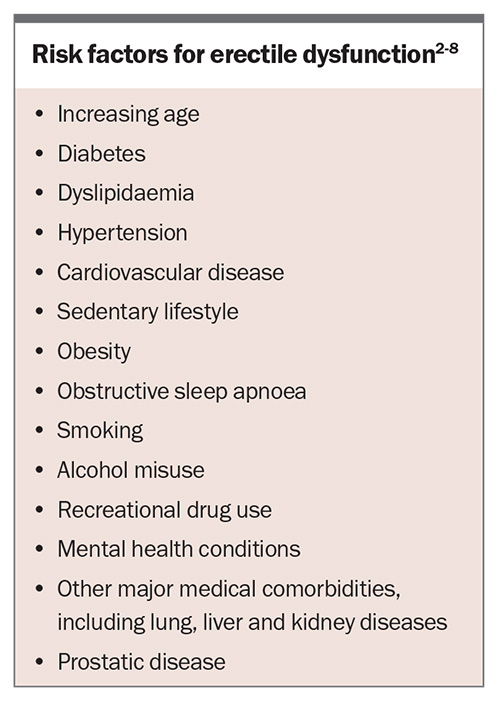

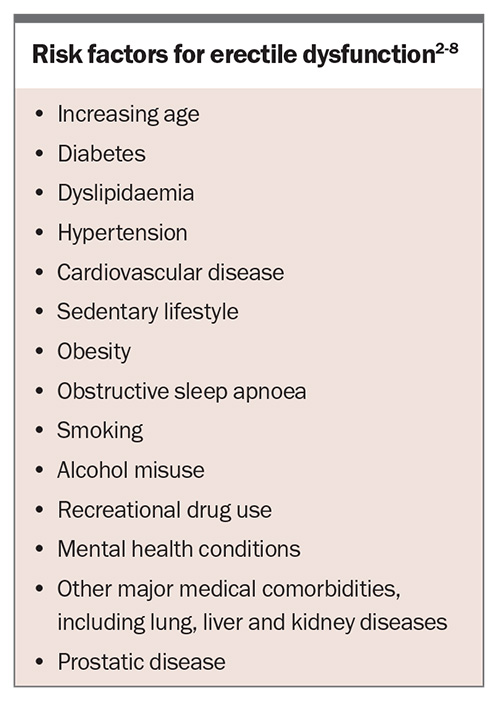

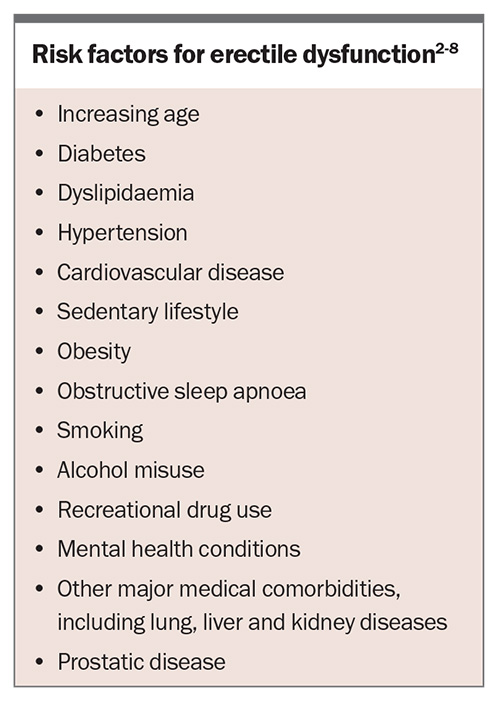

Erectile dysfunction affects a significant proportion of men, with one Australian study reporting a prevalence of 21% for moderate to severe erectile dysfunction in men of all ages.2 Its prevalence increases with age, ranging from 4% in men aged 40 to 49 years to as high as 68% in men aged 70 to 79 years (Figure).2 Other risk factors for erectile dysfunction are listed in the Box.2-8

Diabetes has been shown to have a strong association with erectile dysfunction. A recent meta-analysis of 145 studies of men with diabetes found a prevalence of erectile dysfunction of 52.5%. Compared with healthy controls, men with diabetes were 3.62 times more likely to have erectile dysfunction.9 In Australia, erectile dysfunction has been reported in almost two-thirds of men with diabetes.10 The association is present for all types of diabetes, but particularly type 2 diabetes. It is estimated that men with diabetes develop erectile dysfunction 10 to 15 years earlier than men without diabetes.9

Mechanisms

The physiology of penile erection is predominantly vascular and is mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system. In the resting state, vascular smooth muscle in the penis is contracted. Arousal and increased parasympathetic activity lead to nitric oxide release by parasympathetic nerve fibres. This in turn leads to increased levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), resulting in decreased intracellular calcium levels and relaxation of penile vascular smooth muscle.11 The higher volume of blood flow into the corpora cavernosa results in filling of the lacunar spaces and compression of the subtunical venules. This compression decreases venous outflow and, in combination with the increased inflow, leads to high intracavernosal pressure, penile rigidity and erection.11 Disruptions to any of these mechanisms, which are more often seen in men with diabetes, may lead to erectile dysfunction.

Hyperglycaemia is associated with an increase in oxidative stress, due to excess production of advanced glycation end products, hexosamine and protein kinase C, as well as increased stimulation of the polyol pathway. This in turn leads to inflammation, vascular remodelling and vasoconstriction.12 Overproduction of reactive oxygen species further exacerbates oxidative stress and drives vascular complications, such as neuropathy, which is a significant pathogenic factor in the development of erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes. Endothelial dysfunction also occurs, with reduced levels of nitrous oxide and an increase in endothelin 1 leading to vasoconstriction, as well as increased production of tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 leading to thrombosis.12

Testosterone plays a crucial role in male sexual function, and hypogonadism is a recognised cause of erectile dysfunction. Hypogonadism is strongly associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome and is more prevalent in men with diabetes.13 The mechanisms are poorly understood but may include central suppression of the hypothalamic– pituitary–gonadal axis through low-grade inflammation, increased conversion of testosterone to oestrogen via overactivity of aromatase in adipose tissue, or reduced levels of sex hormone binding globulin, which is strongly associated with insulin resistance.14-16

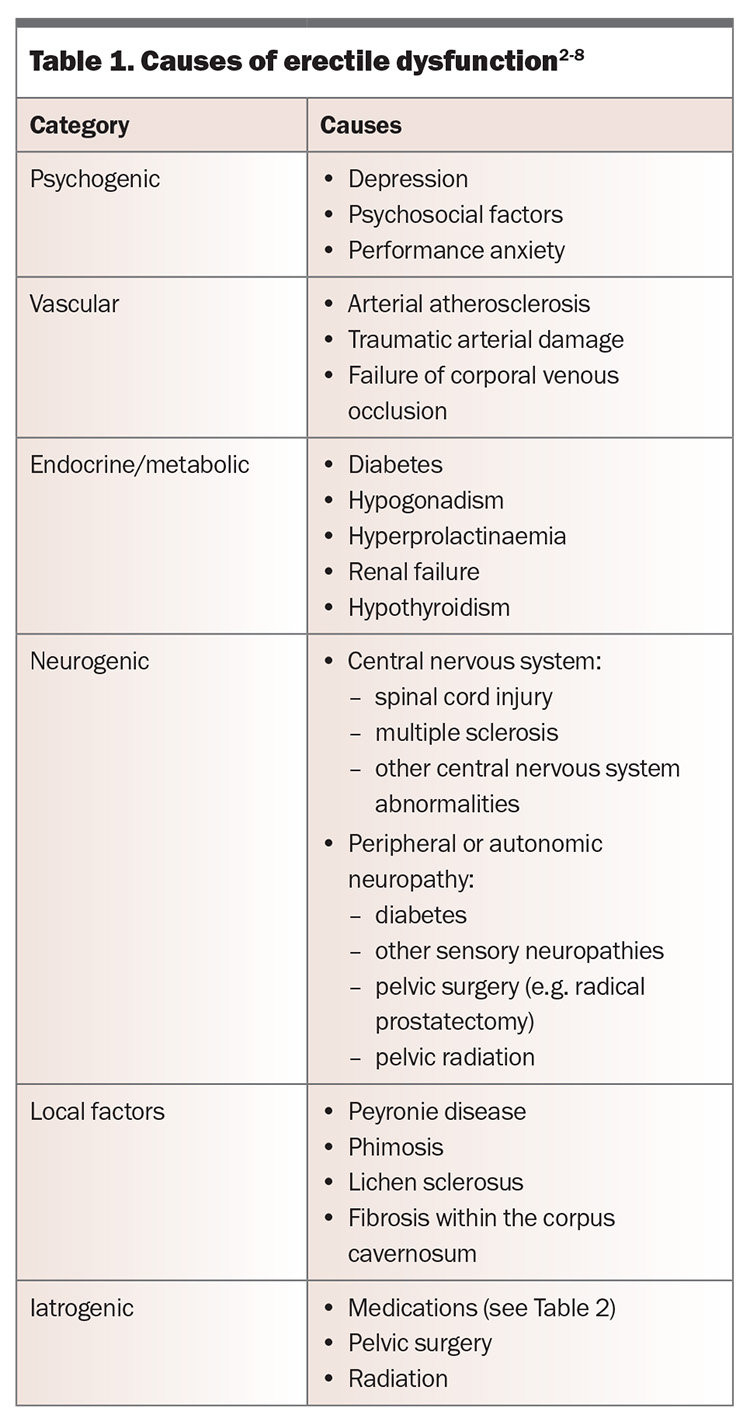

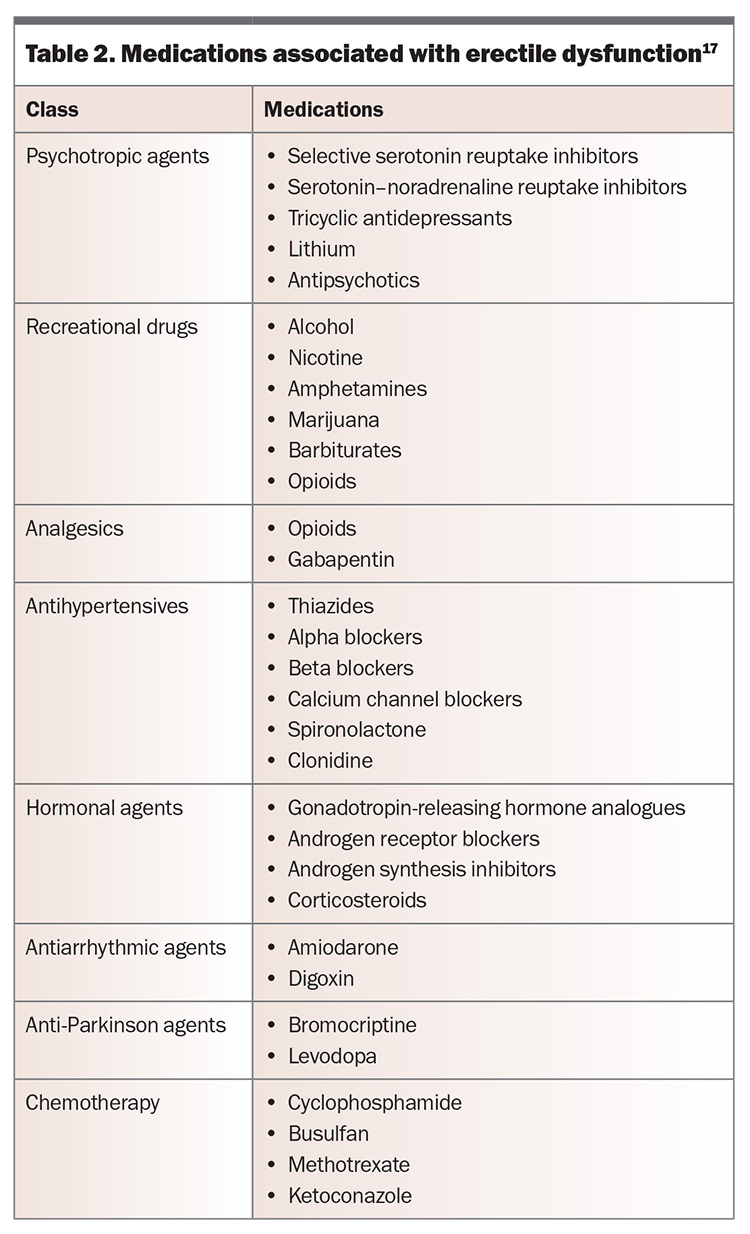

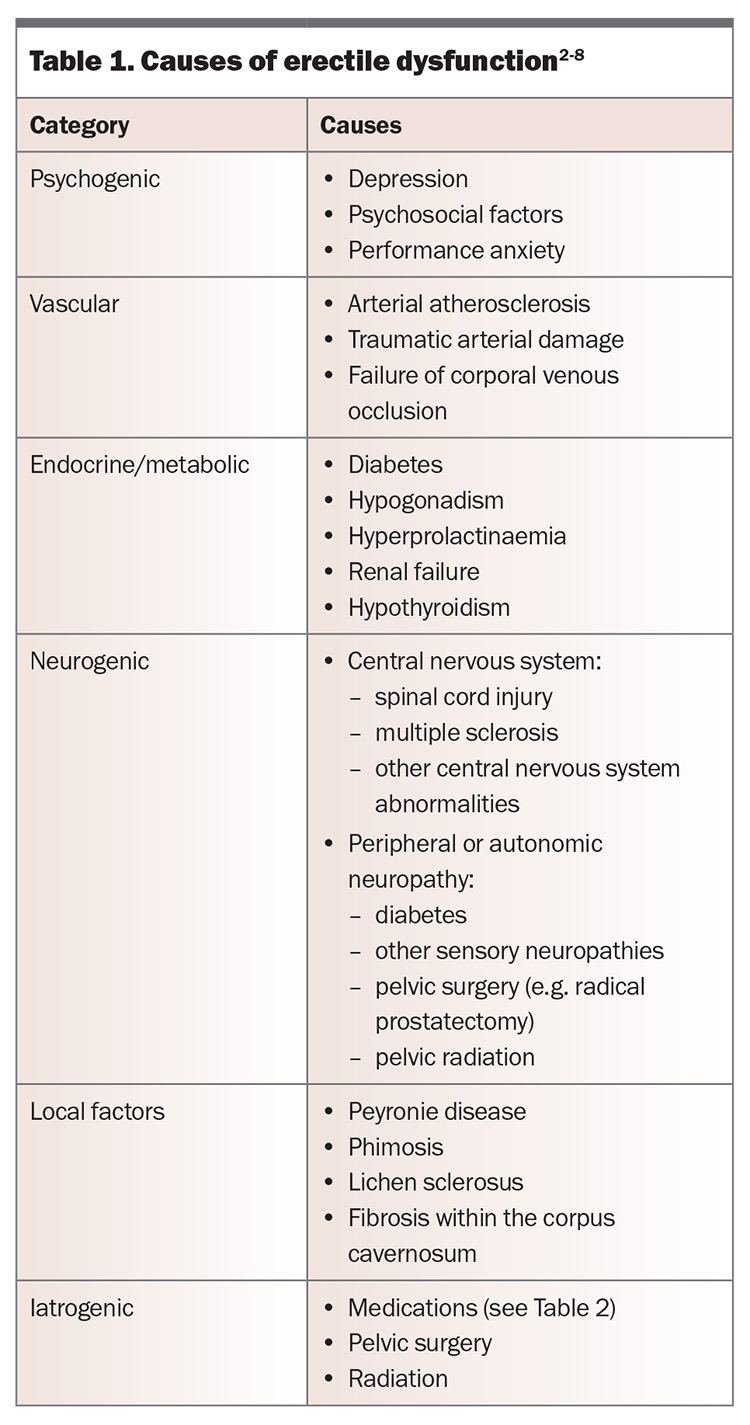

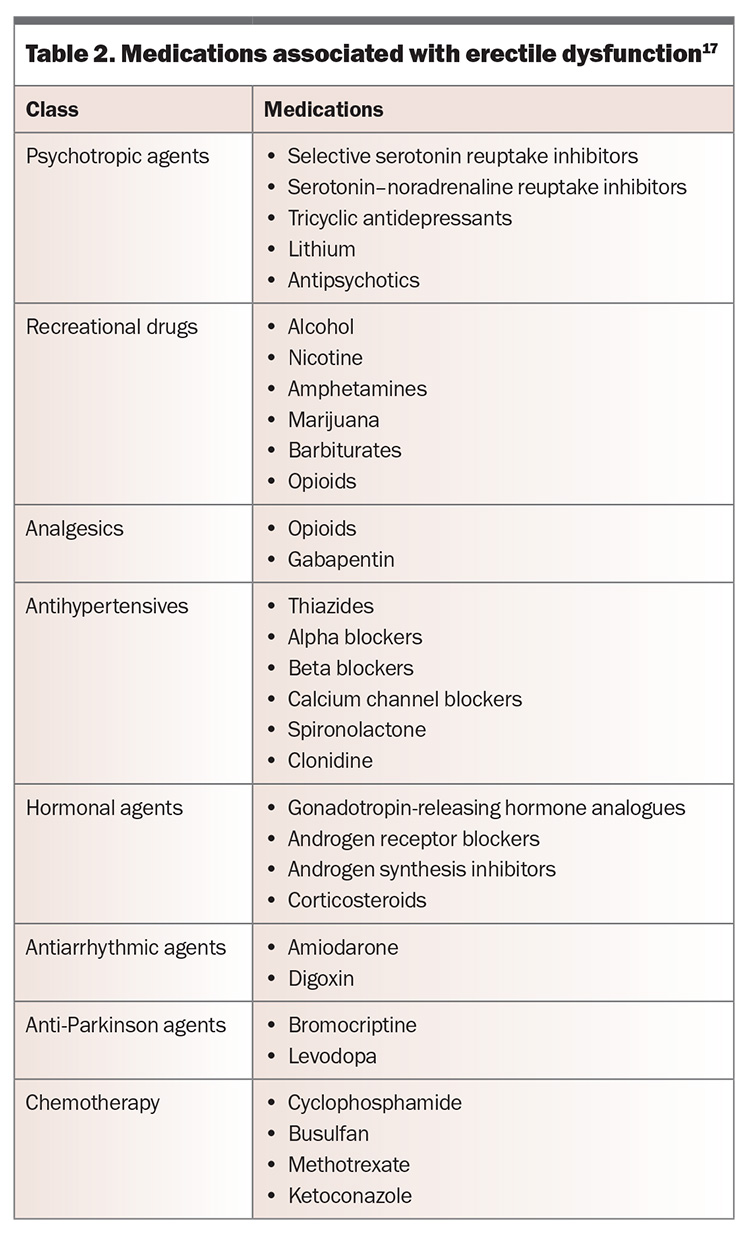

Common causes of erectile dysfunction are presented in Table 1, and medications associated with the condition are shown in Table 2.17

Screening

Although it has a significant impact on a man’s quality of life, only about a third of men with erectile dysfunction in Australia seek advice from a healthcare professional.2 Given the high prevalence of erectile dysfunction, especially in men with diabetes, screening for the condition should be a routine part of diabetes consultations. With their often excellent and longstanding relationships with patients, GPs are uniquely poised to question men who may otherwise be uncomfortable discussing the problem.

Assessment

History and examination

Assessment of men presenting with erectile dysfunction should start with a thorough history and examination. The onset, duration, consistency and overall severity of the condition, as well as the impact on the man and his partner, should be assessed. Men should also be screened for concurrent sexual dysfunction, such as reduced libido or premature ejaculation.

The cause of erectile dysfunction may be psychogenic or organic but is often multifactorial. Psychogenic erectile dysfunction is more often seen in younger men without vascular risk factors, and it may present with a more acute onset. The presence of nocturnal or morning erections may also suggest a psychogenic component. Men should be assessed for any potential underlying risk factors (Box) and contributing comorbidities (such as those listed in Table 1) or medications (Table 2). Progressive worsening of erectile dysfunction may indicate underlying vascular abnormalities.

Men should be examined for structural abnormalities, such as Peyronie disease, corporal plaques or thickening, or phimosis. Men should also have their body habitus assessed, as well as secondary sexual characteristics. Reduced testicular volume and atrophy may indicate hypogonadism. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms, such as hesitancy, poor urine flow and dribbling, are often associated with erectile dysfunction. In older men, or in men of any age if these symptoms are present, prostate examination may be useful.18-20

Erectile dysfunction is an indicator of endothelial dysfunction and has been identified as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.21,22 Therefore, men should be evaluated for the presence of cardiovascular disease before starting treatment.

Laboratory investigations

Consensus guidelines suggest laboratory investigations should include assessment for diabetes with fasting glucose level, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level or glucose tolerance test, a lipid profile and, in select cases, testosterone levels.18,19 Up to 12% of men with erectile dysfunction may have type 2 diabetes.23 Other biochemical investigations, such as prostate specific antigen level and thyroid function, should be individualised.

Guidelines recommend measurement of morning testosterone level in all men with diabetes and those with reduced libido, delayed ejaculation or failure of treatment with phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.18-20 Erectile dysfunction is an uncommon presenting feature of hypogonadism and occurs only at very low levels of testosterone. The incidence of low libido begins to increase with testosterone levels below 15 nmol/L, and erectile dysfunction with levels below 8 nmol/L.24 Measurement of testosterone levels should be repeated, with concurrent luteinising hormone and prolactin levels, if below 12 nmol/L. Levels above this range make a diagnosis of testosterone deficiency unlikely.25 A raised luteinising hormone level suggests primary hypogonadism (i.e. testicular failure), whereas a low level suggests secondary hypogonadism. Pending these test results and other clinical features, further investigation and endocrinologist referral may be indicated.

Specialised tests

Most men do not need specialised testing, but this may be considered for those with lifelong erectile dysfunction, previous pelvic trauma or abnormalities on clinical examination, or before surgical intervention. Before undertaking further investigations, it is important to establish how the result would affect management.18

Nocturnal penile tumescence can be measured by attaching a specialised monitor overnight to assess for the presence of nocturnal erections. The presence of normal nocturnal erections implies a psychogenic aetiology to the erectile dysfunction.18 However, this investigation is not easily accessible in Australia.

In-office testing can be performed with intracavernosal injection of a vasodilatory substance, such as prostaglandin E1, with subsequent examination of the penis for rigidity and deformity. This test may provide some information on vascular status and is useful for assessing for deformity, such as that caused by Peyronie disease.26 However, overriding sympathetic tone related to the anxiety of such a procedure may be problematic.

Penile duplex ultrasound is a specialised investigation that can assess for arterial sufficiency, penile vascular response and veno-occlusive capacity, as well as providing information on the presence of plaques or fibrosis in the corporal bodies.27

Cavernosography involves an intracavernosal injection of radiological dye to diagnose veno-occlusive dysfunction and localise any areas of persistent leakage. It is rarely used nowadays.18 Angiography is only used in select cases of men with previous trauma who may be candidates for revascularisation or men with abnormal duplex haemodynamics.18

Management

Lifestyle management and psychosexual therapy

For all men presenting with erectile dysfunction, it is important to optimise lifestyle and risk factors that may be contributing (Box). Smoking cessation, maintenance of ideal body weight and regular exercise should be advised. Men who started exercising in mid-life have been shown to have up to a 70% reduced risk of erectile dysfunction, compared with those who remained sedentary.28 Erectile dysfunction has also been shown to be significantly relieved in men with obesity who undertake intensive exercise and lose weight.29 In a cohort of men with dyslipidaemia as the only identifiable risk factor for erectile dysfunction, treatment with atorvastatin to lower cholesterol levels resulted in a significant improvement in erectile function.30

Psychosexual therapy should be considered for men for whom a psychogenic component is felt to be a major contributor to their erectile dysfunction. A wide range of treatments, from education through to cognitive behavioural therapy, can be used and are often best combined with medical therapy. Several trials have shown benefit from psychotherapy in addition to the use of medical therapies.31-33

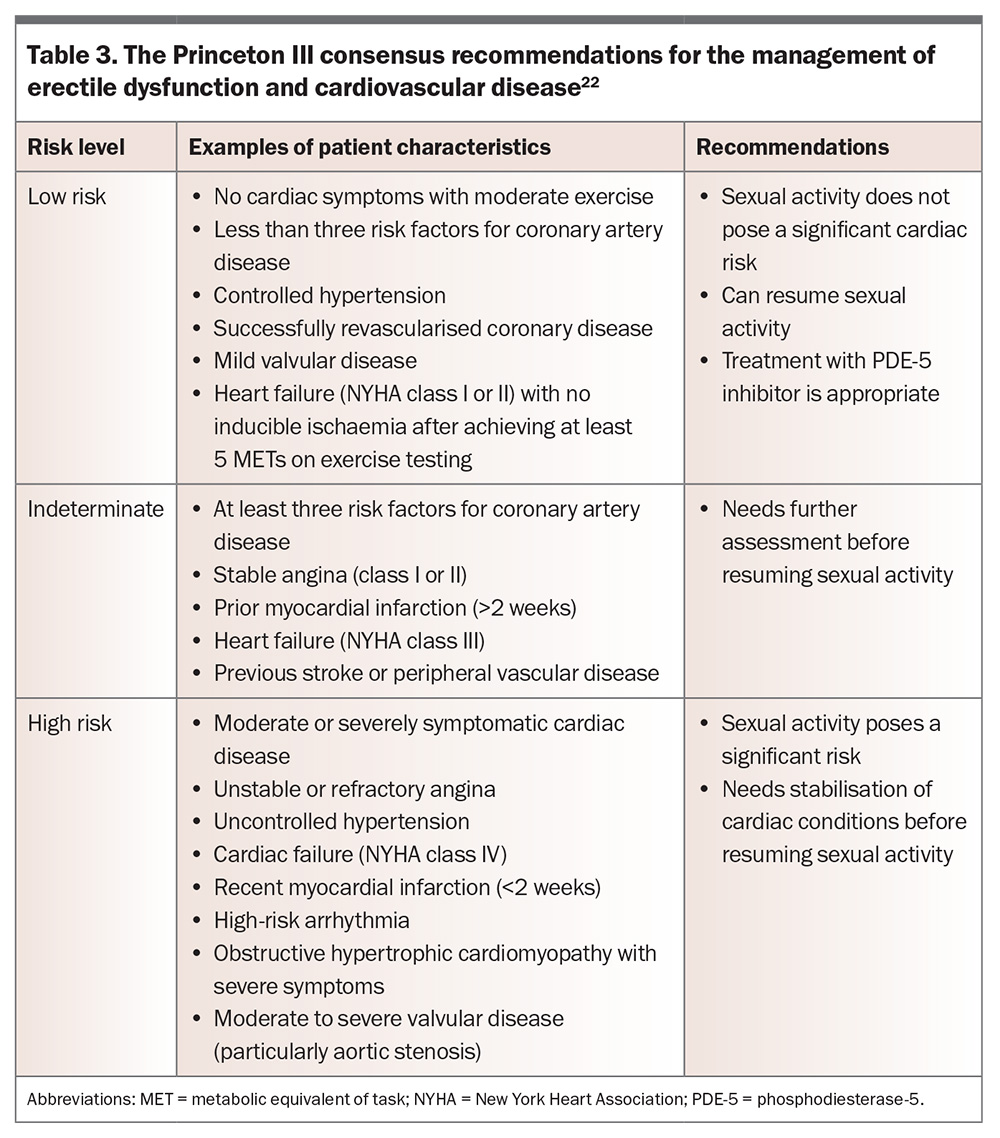

Cardiovascular safety

The cardiovascular safety of sexual activity must be considered for men with erectile dysfunction and known cardiovascular disease (Table 3). Both a man’s exercise tolerance and the severity of his cardiovascular disease must be assessed. Those deemed at low risk can resume sexual activity and appropriately receive treatment with a PDE-5 inhibitor and other therapies. Those deemed at high risk will need stabilisation of their cardiac conditions before resuming sexual activity. Those at indeterminate risk require further assessment.22 Sexual activity by couples with longstanding relationships has been estimated as equivalent to about 3 METs (metabolic equivalents of task), which is similar to sweeping, playing golf with an electronic cart or slow dancing.34 Men of indeterminate risk who are able to complete 5 to 6 METs (4 minutes) on standard Bruce protocol treadmill stress testing without symptoms, fall in blood pressure or arrhythmia are classified as low risk and deemed safe for sexual activity.22 Chemical stress testing should be considered for those not able to perform standard stress testing because of limitations such as poor mobility.

Medical therapy

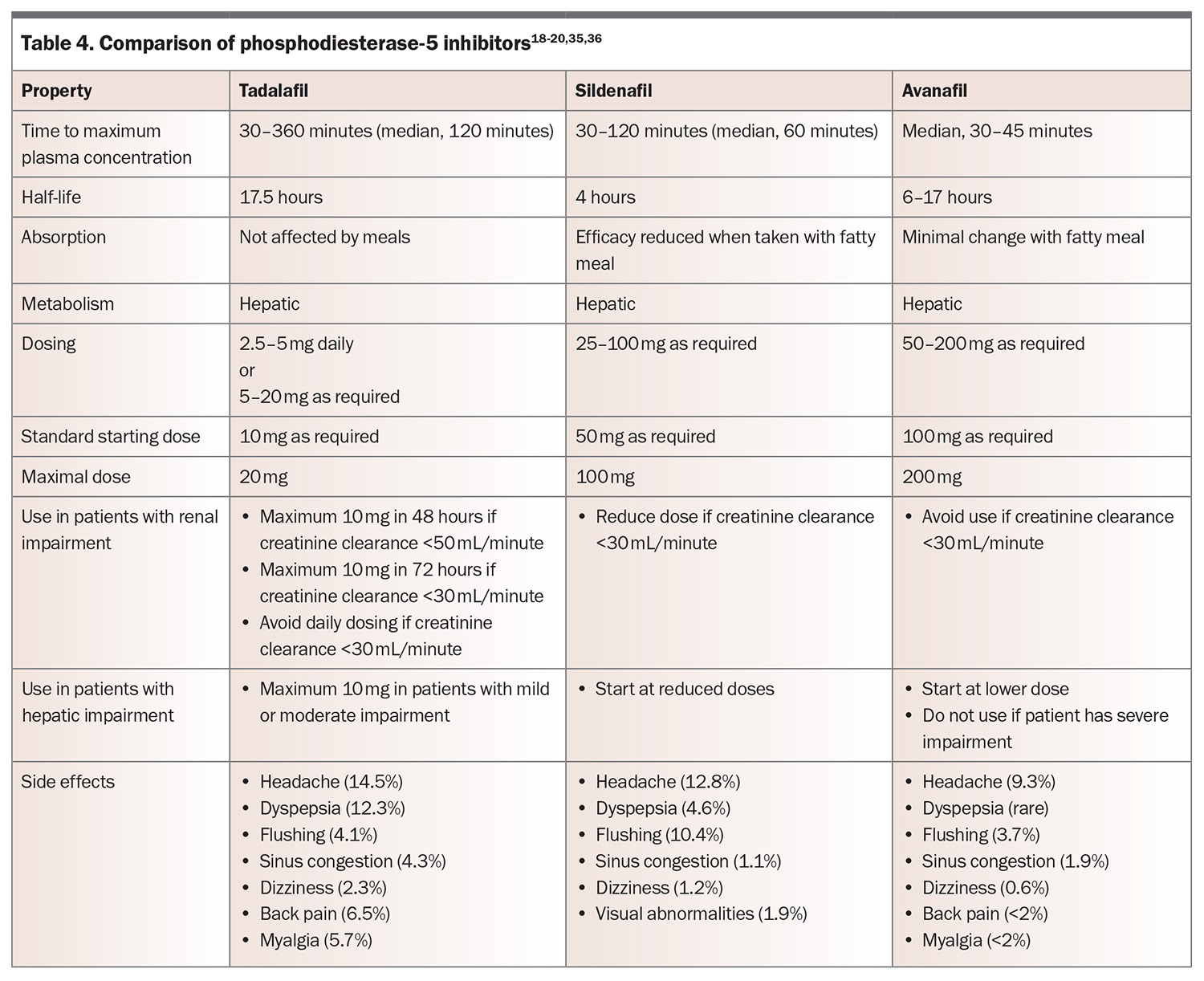

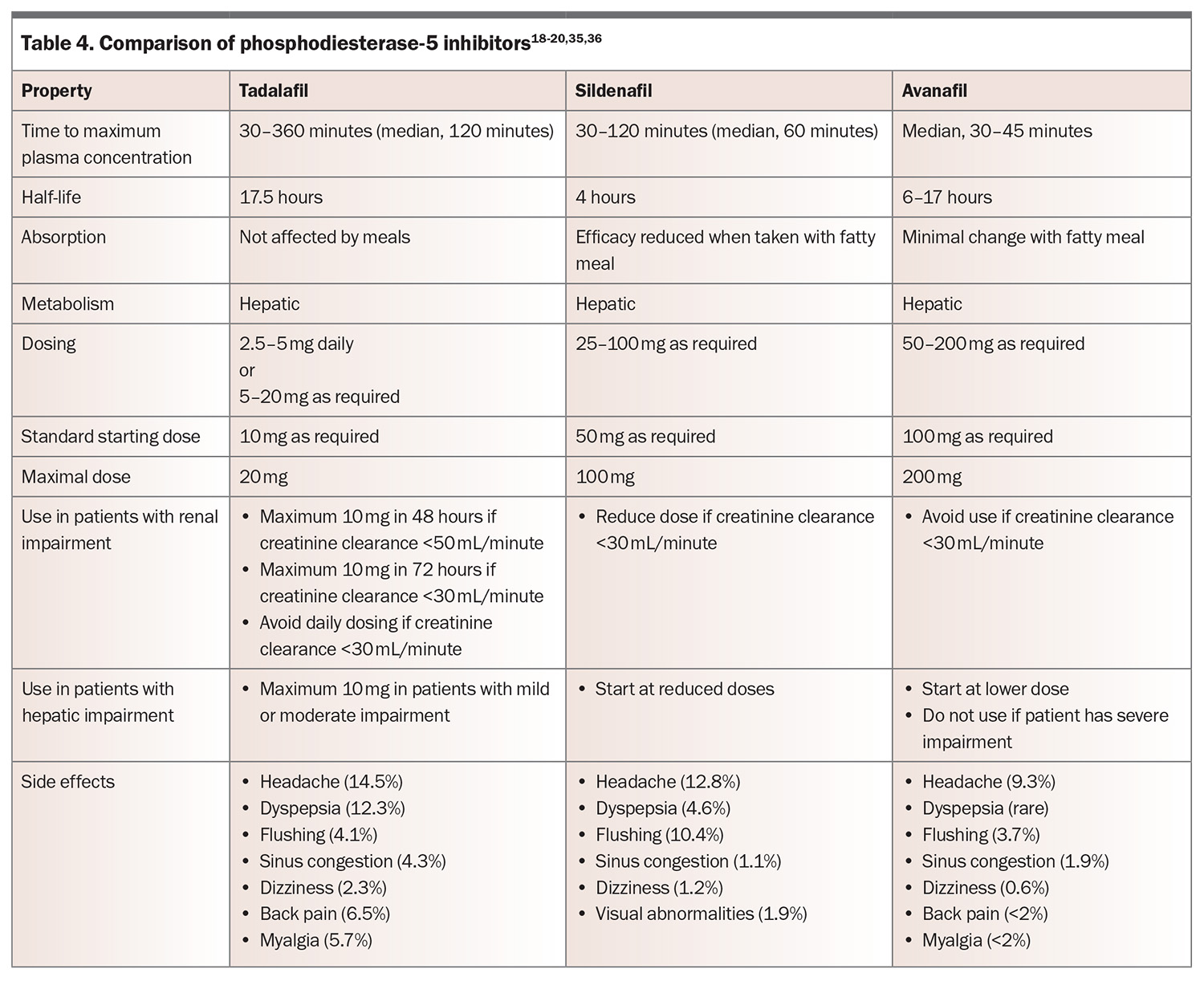

First-line medical therapy for erectile dysfunction is a PDE-5 inhibitor.18 PDE-5 is found predominantly in the vascular smooth muscle of the corpus cavernosum and lungs, and functions by degrading cGMP. Inhibition of PDE-5 results in increased action of vasodilators, such as nitric oxide, which in turn leads to dilation of penile and pulmonary arteries. In Australia, the commercially available PDE-5 inhibitors are tadalafil, sildenafil and avanafil (Table 4).18-20,35,36 These medications are only available on the PBS for men with a Department of Veterans’ Affairs entitlement. There have been no head-to-head comparisons of PDE-5 inhibitors, but they are thought to be similarly effective, resulting in improvement in erections in 67 to 89% of men, compared with 27 to 35% of those taking placebo.37 They are effective across all aetiologies. Choice of medication is therefore based on side effect profile, cost, duration of action and patient preference.

Consider starting PDE-5 inhibitors at lower doses in men aged over 65 years and adjusting doses in those with renal or hepatic impairment. Common side effects include headaches, flushing, sinusitis and dyspepsia. These side effects are dose-dependent but generally only mild to moderate and transient, and they may abate or disappear after four to six weeks of regular use. Rare side effects include priapism or optic changes. PDE-5 inhibitor use is contraindicated in men taking nitrates, as it may precipitate life-threatening hypotension. Sexual stimulation is still required for erection when using PDE-5 inhibitors, and several doses may be needed to establish effectiveness. If patients report drug failure, ensure that the medication was prescribed at an adequate dose, was taken on an empty stomach (for sildenafil) and that adequate time was allowed before sexual stimulation.20 Onset of therapeutic effect often takes 30 minutes or more. If one PDE-5 inhibitor is ineffective, a different one should be trialled.

For men who find the delay from ingestion to onset of effect cumbersome or who engage in frequent sexual activity, tadalafil taken once daily may be used as an alternative. Daily dosing with tadalafil has a comparable efficacy and side effect profile when compared with on-demand dosing of other PDE-5 inhibitors. More detail on dosing for PDE-5 inhibitors is shown in Table 4.

Many supplements are marketed as improving erectile dysfunction, often without evidence of their effectiveness.38 However, a recent meta-analysis concluded that L-arginine (an amino acid), ginseng and Tribulus terrestris could be useful in the treatment of erectile dysfunction, albeit with the trials pertaining to T. terrestris having higher risk of bias and being more heterogeneous.38 None of these supplements form part of major urological guidelines.18-20

Testosterone therapy

The aim of testosterone therapy is to restore physiological androgen status and relieve associated signs and symptoms. Justification for treatment with testosterone is well established for men with a pathological cause of hypogonadism, such as pituitary, hypothalamic or testicular disease. However, there are limited data justifying treatment of older men with low circulating testosterone levels and none of these conditions.39 In men with both testosterone deficiency and erectile dysfunction, therapy with a PDE-5 inhibitor may be more effective if used in combination with testosterone replacement. However, testosterone therapy is not an effective monotherapy for erectile dysfunction.18 Testosterone therapy is contraindicated for men with untreated prostate cancer or unstable cardiac disease. Men should also have baseline measurement of liver function and levels of prostate specific antigen, haematocrit and lipids before starting testosterone treatment.20

Vacuum devices

Vacuum devices increase blood flow into the corpora and use an occlusive ring around the base of the penis to prevent venous return, maintaining an erection.40 These devices may take time to master but are successful in 60 to 70% of men.41 Often used in conjunction with penile rings, they are less invasive than other treatments, so are often trialled as second-line therapy and can be used concurrently with PDE-5 inhibitors.

Combining a PDE-5 inhibitor with a vacuum device can be considered for men with diabetes in whom first-line therapy has failed. Perhaps not surprisingly, the combination has been shown to significantly improve International Index of Erectile Function scores.42 Satisfaction with these devices can be as low as 27% early in treatment, although this improves to as high as 69% after two years.40 Side effects include pain, bruising, paraesthesia, difficulty ejaculating and instability at the base of the penis. The device should not be used for more than 30 minutes because of the risk of developing ischaemia.43

Vasodilating agents

Another option when PDE-5 inhibitors are unsuccessful is intracavernosal injection of vasodilating agents, such as alprostadil. Alprostadil is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue that increases intracellular concentrations of cyclic adenosine monophosphate and therefore leads to vascular smooth muscle relaxation. It must be injected directly into one corporal body at the base of the penis about 15 minutes before intercourse and is effective in more than 70% of men.44 In one trial of 683 men using alprostadil over a six-month period, satisfaction was reported by 87% of men and 86% of their partners.45 In Australia, alprostadil is the only commercially available intracavernosal-injected medication, but in some cases individual medications or combination therapies may be compounded by pharmacies.19 Combination therapy of alprostadil with papaverine and/or phentolamine is effective in 92% of men and can be used for those with severe vasculogenic erectile dysfunction that is unresponsive to other pharmacotherapy.44

Pain is a common side effect of intracavernosal injection, occurring in up to 50% of men, and scarring resulting in curvature or nodules occurs in 9 to 23%.45 Priapism is a potentially devastating side effect that can result in ischaemia and permanent erectile dysfunction, so it should be treated as a medical emergency. All men should be advised of this possible side effect and given advice on the steps to take if it occurs. If an erection lasts for more than two hours, treatment strategies include cold showers, gentle exercise, applying an ice pack to the penis and administration of pseudoephedrine. If a painful erection persists despite these strategies, or for more than four hours, men should present to the nearest emergency department for assessment and drainage.18,19

Intraurethral alprostadil is not commercially available in Australia but is a less invasive alternative, with a lower risk of side effects, and is effective in about two-thirds of men.46 However, poor tolerance because of discomfort is common.

Guidelines recommend in-office trials for all these medications to titrate the dose and educate men on their safe use. Anticoagulation or Peyronie disease are relative contraindications.18

Although most studies of intracavernosal vasodilators include men with diabetes, there are few that focus solely on those with diabetes. It may be that men with diabetes show poorer responses to this treatment. A 2012 retrospective review of 1412 men, of whom 46% had diabetes, showed that intracavernosal injection was nearly three times more likely to fail in those with diabetes.47 In contrast, a retrospective review of 105 men with diabetes using intracavernosal injection showed no obvious difference in efficacy or satisfaction, compared with those without diabetes.48

Surgery

Surgical treatments are generally reserved for patients with disease that does not respond to first-line and second-line therapies. Penile prosthesis implantation has the advantage of on-demand erections as often as required and has been reported to have a satisfaction rate of 86%.18 Implants may be manual multipart pump devices that can be inflated or malleable implants that can be adjusted as required.

There is inherent risk with surgery and use of anaesthesia, but device failure and infections are relatively uncommon.18 Infection rates among all men with penile implants remain low, at about 0.3 to 2.7%. Importantly, men with diabetes seem to harbour an increased risk of infection (odds ratio, 1.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.15–2.04).49 The relation between HbA1c level and penile implant infection remains controversial, with some evidence suggesting an association, whereas other studies find no correlation.50-52 An HbA1c cut-off of 69 mmol/L (8.5%) for penile prosthesis surgery has been suggested.53 However, there is no consensus on this, with a recent systematic review suggesting that the data regarding HbA1c level as a predictor of penile implant infection remain inconclusive.54

In a 15-year database of penile implant procedures performed in California between 1995 and 2010, 11% of men required reoperation within 10 years after surgery (depending on the device used).55,56 The device may be removed in certain settings, such as infection, but treatment should be considered permanent, and erectile function is unlikely to recover without reimplantation of the device. To help prevent complications and reoperations, several authors recommend that penile implantation surgery is carried out only by high-volume implant surgeons.57,58

Although many men with diabetes have peripheral vascular disease, penile arterial revascularisation is rarely performed. However, it may be considered for young men with focal penile arterial occlusion (as opposed to microvascular disease), in the absence of generalised vascular or veno-occlusive disease.19

Other treatments

There is weak evidence for low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy, but it can be employed for mild cases of arteriogenic erectile dysfunction.59 The proposed mechanism of action is induction of neovascularisation. Side effects are minimal, if any.20

Novel therapies, such as intracavernosal stem cell therapy, platelet-rich plasma therapy and radiofrequency treatment, have been investigated, including in men with diabetes.60-62 However, at this stage these are all considered experimental.18,19

Treatment considerations for men with diabetes

For men with diabetes, overall management of erectile dysfunction is similar to that for those without diabetes. However, men with diabetes may be less responsive to PDE-5 inhibitors.63 In a retrospective study of men in the United States, men with diabetes were 60% more likely to seek second-line therapies within five years of diagnosis.64 The use of penile prostheses was also twice as common.27 This may be explained by the more pronounced reduction of cGMP levels and nitrous oxide signalling in men with diabetes, resulting in more severely impaired vasodilation and poorer responses to PDE-5 inhibitors.63 Trialling a daily PDE-5 inhibitor was shown to be effective in one population of men with erectile dysfunction of various aetiologies.65 Daily PDE-5 inhibitor use has also been associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes and lower all-cause mortality.66

Higher HbA1c level is associated with erectile dysfunction, and lowering glucose levels using various agents, including insulin, has been shown to improve erectile function.67,68 Therefore, ensuring adequate glycaemic control is important. Evidence relating to sexual function with use of different antihyperglycaemic agents is limited, but improved endothelial function has been seen with the use of both sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists.69 Given the implications of endothelial function in the pathogenesis of erectile dysfunction, these agents are thought to likely benefit erectile function.69 Animal models have suggested improvement in erectile function with use of both SGLT-2 inhibitors and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.70,71 In addition, among men with obesity who were treated with the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide, testosterone levels improved, and participants reported improved erectile function.72 SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are now considered second-line agents in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, in view of their beneficial cardiovascular and renal effects.73,74 Given the close association of these comorbidities with erectile dysfunction, their use may be indicated in many men, but their direct effect on erectile dysfunction needs further clarification.

Conclusion

Erectile dysfunction is an under-recognised but prevalent problem, especially in men with diabetes, and is associated with significant reductions in quality of life. It is also strongly associated with endovascular dysfunction and predicts cardiovascular disease. Therefore, screening and recognition of men at risk of erectile dysfunction remain important, along with a comprehensive and holistic approach to their assessment and management. Several effective treatments are available. However, further research into novel treatments, especially for men in whom first-line therapy fails, and data regarding the impact of novel diabetes treatments are needed. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Lizza ER, Rosen RC. Definition and classification of erectile dysfunction: report of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Impotence Research. Int J Impot Res 1999; 11: 141-143.

2. Holden CA, McLachlan RI, Pitts M, et al. Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet 2005; 366: 218-224.

3. A Gatti, E Mandosi, M Fallarino, et al. Metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction among obese non-diabetic subjects. J Endocrinol Invest 2009; 32: 542-545.

4. Demir O, Akgul K, Akar Z, et al. Association between severity of lower urinary tract symptoms, erectile dysfunction and metabolic syndrome. Aging Male 2009; 12: 29-34.

5. Bellinghieri G, Santoro D, Mallamace A, Savica V. Sexual dysfunction in chronic renal failure. J Nephrol 2008; 21 Suppl 13: S113-S117.

6. E Huyghe, N Kamar, F Wagner, et al. Erectile dysfunction in end-stage liver disease men. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 1395-1401.

7. Köseoğlu N, Köseoğlu H, Ceylan E, Cimrin HA, Ozalevli S, Esen A. Erectile dysfunction prevalence and sexual function status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Urol 2005; 174: 249-252.

8. Hirshkowitz M, Karacan I, Arcasoy MO, Acik G, Narter EM, Williams RL. Prevalence of sleep apnea in men with erectile dysfunction. Urology 1990; 36: 232-234.

9. Kouidrat Y, Pizzol D, Cosco T, et al. High prevalence of erectile dysfunction in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 studies. Diabet Med 2017; 34: 1185-1192.

10. Weber MF, Smith DP, O’Connell DL, et al. Risk factors for erectile dysfunction in a cohort of 108 477 Australian men. Med J Aust 2013; 199: 107-111.

11. Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1802-1813.

12. Defeudis G, Gianfrilli D, Di Emidio C, et al. Erectile dysfunction and its management in patients with diabetes mellitus. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2015; 16: 213-231.

13. Ding EL, Song Y, Malik VS, Liu S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2006; 295: 1288-1299.

14. Watanobe H, Hayakawa Y. Hypothalamic interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha but not interleukin-6 mediate the endotoxin-induced suppression of the reproductive axis in rats. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 4868-4875.

15. Phé V, Rouprêt M. Erectile dysfunction and diabetes: a review of the current evidence-based medicine and a synthesis of the main available therapies. Diabetes Metab 2012; 38: 1-13.

16. Grossmann M. Low testosterone in men with type 2 diabetes: significance and treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 2341-2353.

17. Baumhäkel M, Schlimmer N, Kratz M, Hackett G, Jackson G, Böhm M. Cardiovascular risk, drugs and erectile function—a systematic analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2011; 65: 289-298.

18. Burnett AL, Nehra A, Breau RH, et al. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline. J Urol 2018; 200: 633-641.

19. Chung E, Lowy M, Gillman M, Love C, Katz D, Neilsen G. Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (USANZ) and Australasian Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine (AChSHM) for the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) clinical guidelines on the management of erectile dysfunction. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 318-324.

20. Hatzimouratidis K, Giuliano F, Moncada I, Muneer A, Salonia A, Verze P. EAU guidelines on erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, penile curvature and priapism. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Barcelona 2019. Arnhem, Netherlands: European Association of Urology; 2019.

21. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2017; 357: j2099.

22. Nehra A, Jackson G, Miner M, et al. The Princeton III consensus recommendations for the management of erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87: 766-779.

23. McKinlay JB. The worldwide prevalence and epidemiology of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 2000; 12 Suppl: S6-S11.

24. Zitzmann M, Faber S, Nieschlag E. Association of specific symptoms and metabolic risks with serum testosterone in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91: 4335-4343.

25. Dean JD, McMahon CG, Guay AT, et al. The International Society for Sexual Medicine’s process of care for the assessment and management of testosterone deficiency in adult men. J Sex Med 2015; 12: 1660-1686.

26. Hatzichristou DG, Hatzimouratidis K, Apostolidis A, Ioannidis E, Yannakoyorgos K, Kalinderis A. Hemodynamic characterization of a functional erection. Arterial and corporeal veno-occlusive function in patients with a positive intracavernosal injection test. Eur Urol 1999; 36: 60-67.

27. Sikka SC, Hellstrom WJ, Brock G, Morales AM. Standardization of vascular assessment of erectile dysfunction: standard operating procedures for duplex ultrasound. J Sex Med 2013; 10: 120-129.

28. Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Feldman HA, Derby CA, Kleinman KP, McKinlay JB. Incidence of erectile dysfunction in men 40 to 69 years old: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol 2000; 163: 460-463.

29. Esposito K, Giugliano F, Di Palo C, et al. Effect of lifestyle changes on erectile dysfunction in obese men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 291: 2978-2984.

30. Saltzman EA, Guay AT, Jacobson J. Improvement in erectile function in men with organic erectile dysfunction by correction of elevated cholesterol levels: a clinical observation. J Urol 2004; 172: 255-258.

31. Banner LL, Anderson RU. Integrated sildenafil and cognitive-behavior sex therapy for psychogenic erectile dysfunction: a pilot study. J Sex Med 2007; 4: 1117-1125.

32. Titta M, Tavolini IM, Dal Moro F, Cisternino A, Bassi P. Sexual counseling improved erectile rehabilitation after non-nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy or cystectomy—results of a randomized prospective study. J Sex Med 2006; 3: 267-273.

33. Melnik T, Abdo CH, de Moraes JF, Riera R. Satisfaction with the treatment, confidence and ‘naturalness’ in engaging in sexual activity in men with psychogenic erectile dysfunction: preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial of three therapeutic approaches. BJU Int 2012; 109: 1213-1219.

34. DeBusk R, Drory Y, Goldstein I. Management of sexual dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease: recommendations of The Princeton Consensus Panel. Am J Cardiol 2000; 86: 175-181.

35. Bella AJ, Lee JC, Carrier S, Bénard F, Brock GB. 2015 CUA Practice guidelines for erectile dysfunction. Can Urol Assoc J 2015; 9: 23-29.

36. Hatzimouratidis K, Salonia A, Adaikan G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for erectile dysfunction: recommendations from the Fourth International Consultation for Sexual Medicine (ICSM 2015). J Sex Med 2016; 13: 465-488.

37. Tsertsvadze A, Fink HA, Yazdi F, et al. Oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors and hormonal treatments for erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 650-661.

38. Petre GC, Francini-Pesenti F, Vitagliano A, Grande G, Ferlin A, Garolla A. Dietary supplements for erectile dysfunction: analysis of marketed products, systematic review, meta-analysis and rational use. Nutrients 2023; 15: 3677.

39. Yeap B, Grossmann M, McLachlan R, et al. Endocrine Society of Australia position statement on male hypogonadism (part 1): assessment and indications for testosterone therapy. Med J Aust 2016; 205: 173-178.

40. Trost LW, Munarriz R, Wang R, Morey A, Levine L. External mechanical devices and vascular surgery for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 1579-1617.

41. Vrijhof HJ, Delaere KP. Vacuum constriction devices in erectile dysfunction: acceptance and effectiveness in patients with impotence of organic or mixed aetiology. Br J Urol 1994; 74: 102-105.

42. Sun L, Peng FL, Yu ZL, Liu C-L, Chen J. Combined sildenafil with vacuum erection device therapy in the management of diabetic men with erectile dysfunction after failure of first-line sildenafil monotherapy. Int J Urol 2014; 21: 1263-1267.

43. Yuan J, Hoang AN, Romero CA, Lin H, Dai Y, Wang R. Vacuum therapy in erectile dysfunction-science and clinical evidence. Int J Impot Res 2010; 22: 211-219.

44. Porst H. The rationale for prostaglandin E1 in erectile failure: a survey of worldwide experience. J Urol 1996; 55: 802-815.

45. Linet OI, Ogrinc FG. Efficacy and safety of intracavernosal alprostadil in men with erectile dysfunction. The Alprostadil Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 873-877.

46. Urciuoli R, Cantisani TA, Carlini M, Giuglietti M, Botti FM. Prostaglandin E1 for treatment of erectile dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (2): CD001784.

47. Coombs PG, Heck M, Guhring P, Narus J, Mulhall JP. A review of outcomes of an intracavernosal injection therapy programme. BJU Int 2012; 110: 1787-1791.

48. Bearelly P, Phillips EA, Pan S, et al. Long-term intracavernosal injection therapy: treatment efficacy and patient satisfaction. Int J Impot Res 2020; 32: 345-351.

49. Gon L, de Campos C, Voris B, Passeri LA, Fregonesi A, Riccetto CLZ. A systematic review of penile prosthesis infection and meta-analysis of diabetes mellitus role. BMC Urol 2021; 21: 35.

50. Bishop J, Moul J, Sihelnik S, Peppas DS, Gormley TS, McLeod DG. Use of glycosylated hemoglobin to identify diabetics at high risk for penile periprosthetic infections. J Urol 1992; 147: 386-388.

51. Wilson S, Delk J 2nd. Inflatable penile implant infection: predisposing factors and treatment suggestions. J Urol 1995; 153 (3 Pt 1): 659-661.

52. Canguven O, Talib R, El Ansari W, Khalafalla K, Al Ansari A. Is Hba1c level of diabetic patients associated with penile prosthesis implantation infections? Aging Male 2019; 22: 28-33.

53. Habous M, Tal R, Tealab A, et al. Defining a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level that predicts increased risk of penile implant infection. BJU Int 2018; 121: 293-300.

54. Dick B, Yousif A, Raheem O, Hellstrom W. Does lowering hemoglobin A1c reduce penile prosthesis infection: a systematic review. Sex Med Rev 2021; 9: 628-635.

55. Mirheydar H, Zhou T, Chang DC, Hsieh T-C. Reoperation rates for penile prosthetic surgery. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 129-133.

56. Enemchukwu EA, Kaufman MR, Whittam BM, Milam DF. Comparative revision rates of inflatable penile prostheses using woven Dacron® fabric cylinders. J Urol 2013; 190: 2189-2193.

57. Onyeji IC, Sui W, Pagano MJ, et al. Impact of surgeon case volume on reoperation rates after inflatable penile prosthesis surgery. J Urol 2017; 197: 223-229.

58. Henry GD, Kansal NS, Callaway M, et al. Centers of excellence concept and penile prostheses: an outcome analysis. J Urol 2009; 181: 1264-1268.

59. Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Capogrosso P, et al. EAU Guidelines on sexual and reproductive health. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress, Paris 2024. Arnhem, Netherlands: European Association of Urology; 2024.

60. Gruenwald I, Appel B, Shechter A, Greenstein A. Radiofrequency energy in the treatment of erectile dysfunction-a novel cohort pilot study on safety, applicability, and short-term efficacy. Int J Impot Res 2023; Aug 17 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1038/s41443-023-00733-1.

61. Iskakov Y, Omarbayev R, Nugumanov R, Turgunbayev T, Yermaganbetov Y. Treatment of erectile dysfunction by intracavernosal administration of mesenchymal stem cells in patients with diabetes mellitus. Int Braz J Urol 2024; 50: 386-397.

62. Mirzaei M, Bagherinasabsarab M, Pakmanesh H, et al. The effect of intracavernosal injection of stem cell in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in diabetic patients: a randomized single-blinded clinical trial. Urol J 2021; 18: 675-681.

63. Angulo J, Gonzalez-Corrochano R, Cuevas P, et al. Diabetes exacerbates the functional deficiency of NO/cGMP pathway associated with erectile dysfunction in human corpus cavernosum and penile arteries. J Sex Med 2010; 7(2 Pt 1): 758-768.

64. Walsh TJ, Hotaling JM, Smith A, Saigal C, Wessells H. Men with diabetes may require more aggressive treatment for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 2014; 26: 112-115.

65. McMahon C. Efficacy and safety of daily tadalafil in men with erectile dysfunction previously unresponsive to on-demand tadalafil. J Sex Med 2004; 1: 292-300.

66. Anderson SG, Hutchings DC, Woodward M, et al. Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor use in type 2 diabetes is associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality. Heart 2016; 102: 1750-1756.

67. Kalter-Leibovici O, Wainstein J, Ziv A, Harman-Bohem I, Murad H, Raz I; Israel Diabetes Research Group (IDRG) Investigators. Clinical, socioeconomic, and lifestyle parameters associated with erectile dysfunction among diabetic men. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1739-1744.

68. Kesavadev J, Sadasivan Pillai P, Shankar A, et al. Exploratory CSII randomized controlled trial on erectile dysfunction in T2DM Patients (ECSIITED). J Diabetes Sci Technol 2018; 12: 1252-1253.

69. Cignarelli A, Genchi VA, D’Oria R, et al. Role of glucose-lowering medications in erectile dysfunction. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 2501.

70. Assaly R, Gorny D, Compagnie S, et al. The favorable effect of empagliflozin on erectile function in an experimental model of type 2 diabetes. J Sex Med 2012; 15: 1224-1234.

71. Harmar AJ, Fahrenkrug J, Gozes I, et al. Pharmacology and functions of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide: IUPHAR review 1. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 166: 4-17.

72. Giagulli VA, CarboneMD, Ramunni MI, et al. Adding liraglutide to lifestyle changes, metformin and testosterone therapy boosts erectile function in diabetic obese men with overt hypogonadism. Andrology 2015; 3: 1094-1103.

73. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2117-2128.

74. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1834-1844.