Travelling with diabetes: empowering patients for safe travel

People with diabetes often encounter challenges while travelling (such as changing time zones, unexpected delays and unreliable cold storage of medications). Healthcare professionals play an important role in preparing patients before travel and ensuring that they are well equipped for their journey in terms of physical equipment and with clear management plans in place, so that people with diabetes can travel safely.

- Patients with diabetes should ideally see their GP, diabetes educator or endocrinologist six weeks before travel to review sick-day management plans and ensure that they are well equipped and prepared for their journey.

- Common challenges encountered while travelling include changing time zones, unfamiliar environments, irregular access to food, unexpected delays and unreliable cold storage of medications. These challenges can be overcome with appropriate preparation and patient education.

- Certain activities (e.g. swimming, hiking, scuba diving) are more challenging when patients are on insulin and careful planning is required to ensure patients can undertake these activities successfully and safely.

- Advanced planning with clinicians plays an important role in empowering patients with diabetes to travel successfully.

Living with diabetes can be challenging and this is often amplified when travelling. Dealing with changing time zones, unfamiliar environments, irregular access to food, unexpected delays and unreliable cold storage of medications are some of the difficulties patients face while overseas. A safe and enjoyable trip requires advanced planning, and clinicians play an important role in empowering patients with diabetes to travel successfully.

Pre-travel advice

Patients with diabetes should ideally see their GP, diabetes educator or endocrinologist six weeks before travel. During this consultation, a review of sick-day management should occur, highlighting the potential increased risk of infection associated with travel and the effect this may have on blood glucose levels. Travelling with ketone strips is essential for people with type 1 diabetes.

It is advised that clinicians provide patients with a letter clearly stating the patient’s personal details, diagnosis, associated medical conditions, medications used and doses, and any devices that may be used to assist in managing their diabetes. The letter should also detail storage instructions of medications such as insulin, the importance of carrying all medications and diabetes-related equipment on their person (including hypoglycaemia treatment), and that medical devices such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices and insulin pumps should never be removed. Patients should carry multiple copies of this letter and, if possible, this information should be translated into the destination language to assist with communication. A digital version (e.g. stored in the virtual cloud or emailed) of this letter is also useful while abroad and a copy stored with travel companions. Consideration of a medical alert bracelet or wallet card indicating a diabetes diagnosis can be helpful, especially if travelling alone. Patients should be advised to have their medications clearly labelled in their original packaging – pharmacies can assist in the preparation of this. All immunisations should be up to date and will vary for specific destinations. Counselling should be given on lifestyle choices (such as maintaining a healthy diet, moderating alcohol intake, planning exercise) and the impact these can have on diabetes management while abroad. Consider creating a list of relevant helplines to call for technological support for patients using devices.

Travel insurance

It is important to advise patients of the need for travel insurance while abroad but highlight that most insurance providers consider diabetes to be a pre-existing diagnosis, which can incur extra expenses. Most providers will also require supporting documentation from a medical practitioner and, at times, an independent medical assessment before providing insurance. Costs vary significantly depending on the countries visited, activities undertaken, technology used, diabetes-related complications and the stability of diabetes over the 12 months prior to travel.

Navigating airports

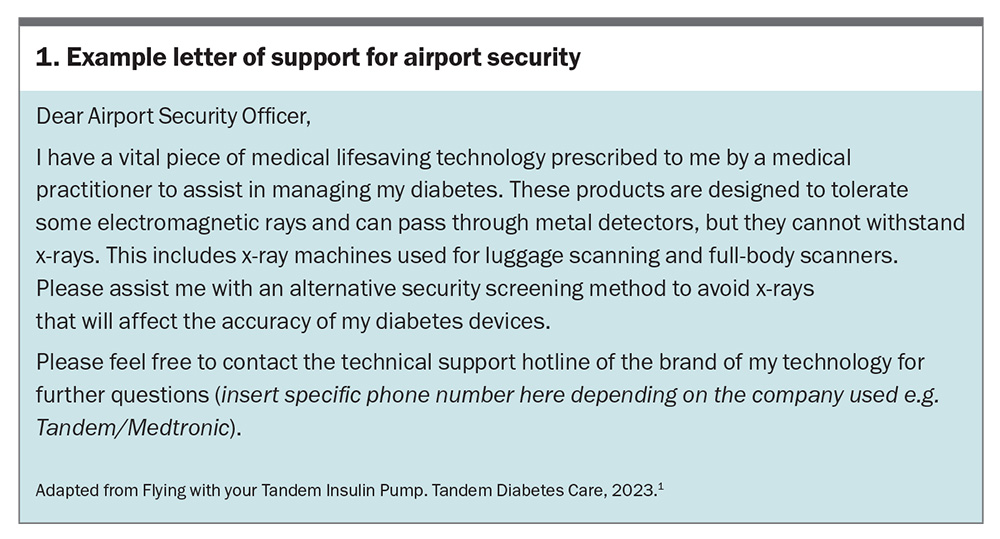

When travelling, it is crucial that people with diabetes arrive extra early for flights and plan for longer transit times when changing flights. Passing through airport security can be more difficult and a time-consuming process, especially if a person is carrying diabetes technology. Modern-day body scanners can interfere with the function of some devices. People using CGM devices are advised to avoid using full-body scanners that emit electromagnetic radiation and can cause sensor malfunction.

The easiest way to avoid removing any technology is to request a manual security assessment using a handheld metal detector wand. The functions of insulin pumps, infusion sets, reservoirs and CGM systems are not influenced by exposure to airport metal detectors. In contrast, insulin pump and CGM device functions can be influenced by x-rays, so when carrying spares in carry-on luggage, a manual inspection should be requested to avoid damage to these devices. Some companies that handle the distribution of insulin pumps and CGM devices can also provide a pre-written document that is device specific for people to show to airport security to assist in the request for a manual check (Box 1 and Figures 1a to d).1

Carry-on luggage checklist

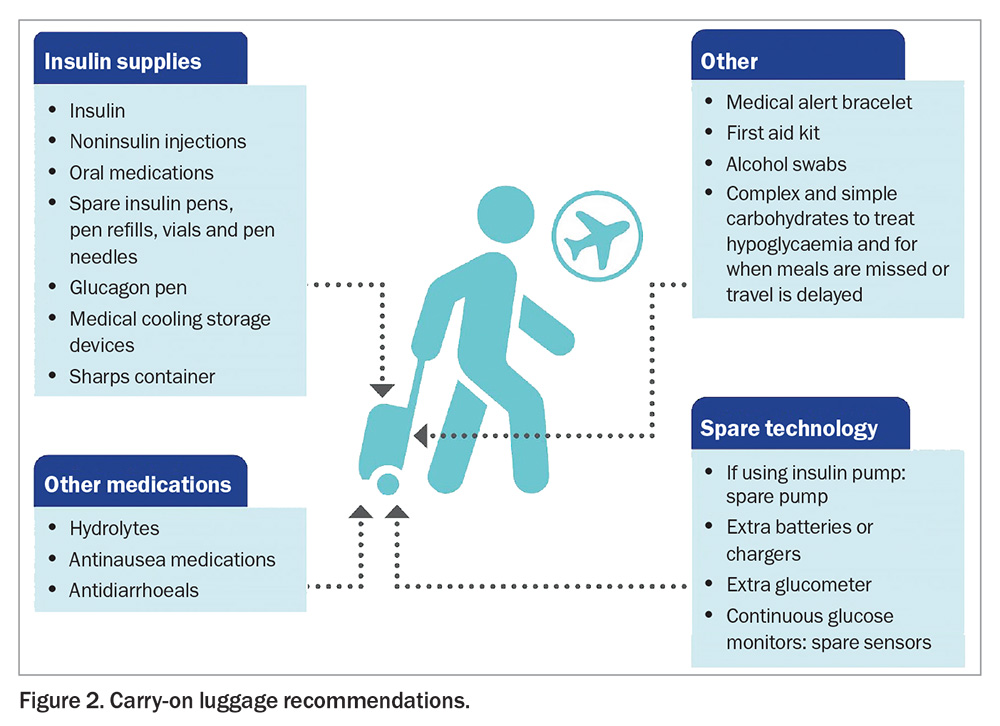

Ideally, all diabetes medications and accessories should be kept in carry-on luggage; however, to negate the possibility of lost or stolen carry-on luggage, spare supplies can be included in checked luggage. People with diabetes should be aware that extremes of temperature cannot be predicted in cargo holds and this may affect the potency of insulin. Most airlines allow additional weight for medical equipment that is not included in standard weight limits. Advise patients to contact their airline and investigate the added amount of medical equipment allowed, as this can vary between airlines. A packing guide for carry-on luggage is shown in Figure 2.

In-flight tips

CGM devices are safe to use on most commercial airlines. Smartphones can be used in airplane mode and it is important to advise patients that Bluetooth must be kept on to be able to receive sensor glucose information to their smartphone or smartwatch. If patients have set up the data sharing feature with family members, this will not be available in-flight unless there is onboard Wi-Fi. Insulin pumps are safe to use on commercial flights and also require Bluetooth to connect to devices. Diabetic meals provided by airlines often contain minimal carbohydrates and can contribute to hypoglycaemia when combined with low oxygen tension and alcohol consumption. Ensuring adequate hydration throughout the flight is important.

The changes in cabin pressure that occur with ascent and decent during a flight affect insulin delivery via insulin pumps and may therefore affect blood glucose levels.2 In a flight simulation study, 0.6 units of insulin was found to be over-delivered during a 20-minute ascent and 0.51 units was found to be under-delivered during descent via the use of an insulin pump.3 This occurs because of the formation of air bubbles in insulin as the ambient pressure decreases. When the aircraft ascends, air bubbles form and cause insulin to be displaced within the pump, and when the aircraft descends, the air bubbles redissolve.2 However, it should be noted that in a real-world evaluation, pilots using insulin pump therapy in-flight did not experience a fall in blood glucose levels or episodes of hypoglycaemia during atmospheric pressure changes.3 For an insulin-sensitive patient, these small changes in insulin delivery may cause hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia. Patients should be made aware of this phenomenon and act appropriately if required, such as having a small snack on ascent and disconnecting the pump after descent to reprime the line, thereby removing any insulin undersupply.

Insulin pump failure

Pump malfunctions can occur while travelling and it is important to have a backup plan. Some companies offer a spare travel pump that can be hired for an affordable fee. In the event of pump failure without a backup pump available, patients will need to revert back to multiple daily insulin injections. Therefore, it is important that patients are aware of their daily insulin requirements, including daily basal dose and meal bolus doses (either by dividing their total daily bolus dose across their meals or using their carbohydrate ratio and insulin sensitivity factor to manually calculate their meal boluses).

Travelling across time zones

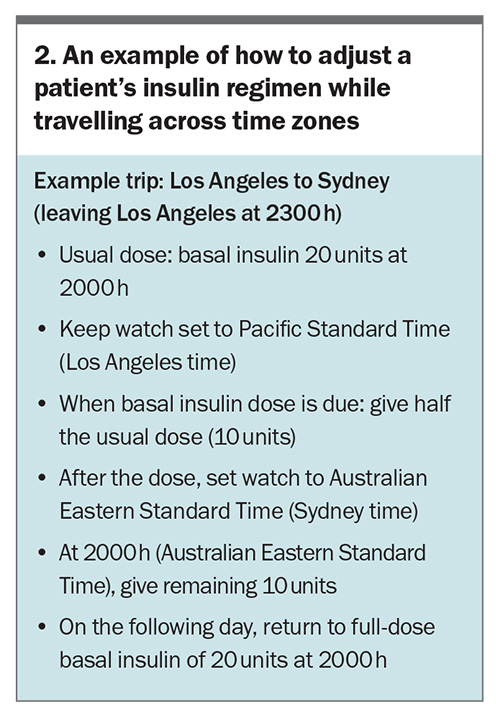

Diabetes management is based on a 24-hour medication schedule. There is very little standardised information available regarding manual insulin adjustment strategies across time zones. The use of insulin pumps somewhat simplifies the process – patients can adjust the time on the pump and then continue as usual. Patients using multiple daily injections should be advised to wear a watch and set it to the time zone of embarkation to assist with the timing of insulin and plane meals. Travelling east will shorten a person’s day and travelling west will lengthen it.

For shorter trips, if travelling across fewer than five time zones or for less than three days, there is no need to change the insulin regimen. The aim is to keep things simple and avoid hypoglycaemia, especially in flight, even if it means a short period of suboptimal glucose control. For longer trips, if travelling east, which will shorten the day, consider a 4% dose reduction for each time zone that is crossed, where one hour is 4% of the 24-hour day.4 For westward travel, consider split dosing of basal insulin to account for the lengthening of the day.

A written plan can be developed between the patient and medical practitioner to assist with insulin adjustments and avoid any errors when patients are travelling across time zones (see the example in Box 2). As travel is unpredictable with flight delays, flexibility with this plan is important and patients should be encouraged to increase regular glucose monitoring.

Insulin storage

It is important that insulin is stored correctly to maintain efficacy. Manufacturer guidelines recommend that an unopened cartridge of insulin should be refrigerated at 4 to 6°C and not allowed to freeze. Ideally, once the cartridge has been inserted into the injection pen, it should not be placed back in the refrigerator and should be stored below 30°C (ideally between 20 and 25°C). When not in use, it should be stored in a cool, dry place away from moisture, heat or direct sunlight. The same principles apply to single-use prefilled pens. Before first use, insulin should be allowed to reach room temperature for one to two hours before administration. After 28 days from first use, it should be discarded, which includes spare pens kept out of the refrigerator. Transporting the sheer volume of insulin required for a lengthy overseas trip can be problematic, but there are medical cooling storage devices that can be useful. Switching patients from prefilled pens to reuseable pens and pen refills will save on storage. Portable sharps containers are also available in most airports, providing a needle disposal program.

Challenges of travel on insulin therapy

Certain activities are more challenging when patients are on insulin and careful planning is required to ensure patients can undertake these activities successfully and safely. Food and physical activity may vary significantly while on holiday and for a person using insulin, education needs to be provided for potential adjustments to dosing. If using an insulin pump that is to be removed for an extended period of time, a plan for changing to manual insulin injections should be in place.

Hiking at altitude

The level of altitude reached will have a different effect on blood glucose levels. At high altitudes, blood glucose levels decrease in response to exercise, whereas very high altitudes cause hyperglycaemia in response to exercise. It is crucial that patients are aware of these considerations and seek specialist advice on how this might affect their insulin regimen. Acute mountain sickness (AMS), including symptoms of headache, nausea, dizziness and fatigue, can often be confused with symptoms of hypoglycaemia. AMS can vary from self-limiting to potentially lethal pulmonary oedema. Although there does not seem to be an increased incidence of AMS in people with diabetes, treatment for AMS may pose a risk for metabolic disturbances in people with diabetes. Acetazolamide, a treatment for AMS, causes diuresis and acidosis, which can increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). In severe AMS, dexamethasone may be indicated, and this could lead to hyperglycaemia, DKA or hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome. Additionally, there is already an increased risk of DKA caused by dehydration secondary to fluid loss and tendency towards hyperglycaemia at high altitudes.

Handheld glucose monitors are affected by environmental conditions such as extreme cold. Insulin, test strips, ketone strips, batteries and blood glucose monitors must be kept above freezing point. Therefore, it is best that this equipment is carried close to bare skin and under layered clothing while hiking.

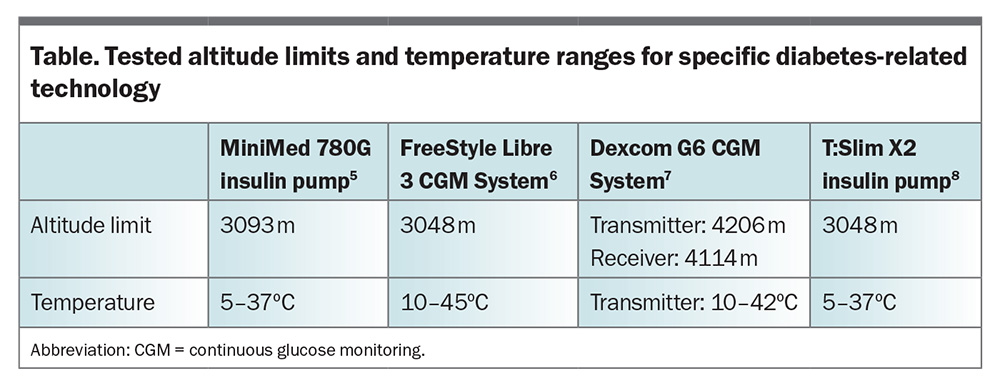

The limits of reliable performances of various diabetes-related technology devices vary according to altitude and temperature. Most manufacturer guidelines advise that their equipment has only been tested at certain altitude and temperature ranges (Table).5-8

Swimming

All insulin pumps are water resistant at the time of purchase; however, if the outer shell becomes damaged, then this might compromise the function of a pump when exposed to water. It is recommended that insulin pumps be removed while swimming. Patients should not leave insulin pumps detached for more than one hour; therefore, the duration of water-based activity will need to be limited. Guidelines recommend to aim for a blood glucose level of above 7 mmol/L before swimming and to eat 15 g of carbohydrates for every 30 to 60 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise.9 CGM devices rely on Bluetooth to communicate with devices such as smartphones and smartwatches and they generally have a maximal range of 6 metres, so when swimming further, the signal between devices could be lost.

Scuba diving

Recreational diving in people with diabetes is achievable with care, and a protocol has been developed by the Australian Diabetes Society that provides clear blood glucose targets before immersion.10 It is advised to remove all diabetes-related technology when preparing to dive.

Summary

Travel in people with diabetes requires significant planning but with appropriate resources this can be achieved safely. Healthcare professionals play an important role in preparing patients before travel and ensuring that they are well equipped for their journey in terms of physical equipment and with clear management plans in place. Clinicians should encourage patients to pack double the equipment and insulin supplies that they might need so they are prepared for the ever-changing scenarios that occur while travelling. Revisiting the symptoms and signs of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemic emergencies with patients before they travel is also advisable. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Seaton, Dr Cox, Mr Uren and Dr Hong: None. Professor MacIsaac has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer and Servier; speaker fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly; support for attending meetings from Novo Nordisk; and grants from St Vincent’s Hospital, The Australian Government, Medtronic, Glysens and Pacific Diabetes Technologies. Professor O’Neal has received lecture fees from, and is on the Advisory Boards of, Abbott, Insulet and Medtronic; and received grants from Abbott, Insulet, Medtronic and Sanofi-Aventis.

References

1. Flying with your Tandem Insulin Pump. Tandem Diabetes Care; 2023. Available online at: https://amsldiabetes.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/PR-100-267-Flying-with-your-tslim-X2-Insulin-Pump.pdf (accessed November 2024).

2. King BR, Goss PW, Paterson MA, Crock PA, Anderson DG. Changes in altitude cause unintended insulin delivery from insulin pumps: mechanisms and implications. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1932-1923.

3. Garden GL, Fan KS, Paterson M, et al. Effects of atmospheric pressure change during flight on insulin pump delivery and glycaemic control of pilots with insulin-treated diabetes: an in vitro simulation and a retrospective observational real-world study. Diabetologia 2024; doi: 10.1007/s00125-024-06295-1. Online ahead of print.

4. Pinsker JE, Becker E, Mahnke CB, Ching M, Larson NS, Roy D. Extensive clinical experience: a simple guide to basal insulin adjustments for long-distance travel. J Diabetes Metab Disorder 2013; 12: 59.

5. MiniMedTM 780G System User Guide. Medtronic; 2024. Available online at: https://www.medtronicdiabetes.com/sites/default/files/library/download-library/user-guides/MiniMed-780G-system-user-guide-with-Guardian-4-sensor.pdf (accessed November 2024).

6. FreeStyle Libre 3 Continuous Glucose Monitoring System. User’s Manual. Abbott Diabetes Care Inc; 2022-2023. Available online at: https://freestyleserver.com/payloads/ifu/2023/q3/ART41641-001_rev-A-web.pdf (accessed November 2024).

7. DexcomG6. Using your G6. Dexcom, Inc; 2020. Available online at: https://amsldiabetes.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/MT26356-Dexcom-G6-User-Guide.pdf (accessed November 2024).

8. t:slim X2. User Guide. Tandem Diabetes Care; 2018. Available online at: https://amsldiabetes.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/tslim-X2-Insulin-Pump-User-Guide.pdf (accessed November 2024).

9. Riddell MC, Gallen IW, Smart CE, et al. Exercise management in type 1 diabetes: a consensus statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017; 5: 377-390.

10. Kyi M, Paldus B, Nanayakkara N, et al. Insulin-requiring diabetes and recreational diving: Australian Diabetes Society (ADS) position statement. Diving and diabetes–ADS position statement, 2016. Available online at: https://media.anzsped.org/2017/10/17125342/ADS_Diving_Diabetes_2016_Final.pdf (accessed November 2024).