Diagnosing and managing diabetic gastroparesis

Diabetic gastroparesis is a frequent and complex disorder with clinical consequences beyond upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Management may be demanding and is often refractory to first-line pharmacological therapies, dietary modification and optimisation of glycaemic control. A multidisciplinary approach with specialist input is often required.

- Delayed gastric emptying and upper gastrointestinal symptoms occur frequently but correlate poorly in people with longstanding type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- The efficacy of current prokinetic and antiemetic therapies in treating symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis is limited.

- In insulin-treated patients, delayed gastric emptying may lead to a mismatch between the timing of insulin action and carbohydrate absorption, predisposing them to hypoglycaemia.

- Measurement of gastric emptying using either a stable isotope breath test or scintigraphy is needed to establish the diagnosis.

- Management of diabetic gastroparesis is often complex and specialist input is recommended.

Gastroparesis refers to a delay in gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction and occurs frequently in people with longstanding type 1 or type 2 diabetes (prevalence 30 to 50%).1,2 Risk factors for gastroparesis include having diabetes for more than 10 years, chronic suboptimal glycaemic control, as assessed by measurement of glycated haemoglobin level, autonomic neuropathy and, possibly, cigarette smoking.3 Evaluation for potential gastroparesis should be considered in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who experience recurrent symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness, bloating or abdominal discomfort. Such symptoms are often not volunteered, but occur frequently in people who have diabetes and adversely affect quality of life. This article outlines the assessment and management of this important condition.

Clinical considerations

Gastroparesis may have important clinical consequences, even in the absence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms. For example, in people with insulin-treated diabetes, it may be associated with recurrent postprandial hypoglycaemia.4 Individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes are often instructed to administer short-acting insulin before or with a meal; however, a delay in gastric emptying increases the risk of insulin action occurring before the absorption of nutrients.4 Furthermore, patients with other comorbidities who require time-critical medications (e.g. levodopa for treatment of Parkinson’s disease) may have a suboptimal response to these medications due to a delay in intestinal absorption.5

A common and longstanding misconception is that a delay in gastric emptying, particularly when marked, is closely associated with upper gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting; however, symptoms and the rate of gastric emptying correlate only weakly.6 Accordingly, a marked delay in gastric emptying may occur in the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms while, conversely, bothersome upper gastrointestinal symptoms may not be associated with any delay in gastric emptying.6 Furthermore, gastric emptying is now recognised to often be accelerated, particularly in those with uncomplicated type 1 or type 2 diabetes.7 Abnormally slow gastric emptying cannot be discriminated from more rapid gastric emptying on the basis of symptoms. Therefore, it is essential to confirm the diagnosis of gastroparesis using a suitable method.

Recent data on full-thickness gastric biopsies from patients with severe refractory gastroparesis from the Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium showed that the pathophysiology of diabetic gastroparesis is complex and heterogeneous.8 As such, an empirical approach to treatment may not prove effective, which complicates the management of this condition.

Evaluation of suspected gastroparesis

In individuals with suspected gastroparesis and upper gastrointestinal symptoms, differential diagnoses to consider include gastric outlet obstruction, medication adverse effects (e.g. from opioids, glucagonlike peptide-1 agonists), cannabis hyperemesis syndrome and rumination syndrome. Gastroparesis should also be suspected in patients with diabetes experiencing frequent, unexplained postprandial hypoglycaemia, even without upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Physical examination is generally unremarkable. Individuals with gastroparesis are more frequently nutrient deficient than the general population, especially in iron (50%) and vitamins D (50%) and B12 (18%).9 Therefore, evaluation for nutritional deficiencies should be considered in those with suspected gastroparesis.

In patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms, an endoscopy is required to exclude gastric outlet and proximal small intestinal obstruction. However, the presence of retained gastric food at endoscopy is not a strong indicator of gastroparesis, with a positive predictive value of only 55%.10

The standard test to confirm the diagnosis of gastroparesis is scintigraphy; however, the stable isotope breath test is an acceptable alternative if the former is not readily available.11 The stable isotope breath test is also more simple to perform and is not associated with a radiation burden; however, it cannot discriminate changes in gastric emptying from those in small intestinal absorption or transit. Current US guidelines recommend a test meal of eggs, toast, jam and water with only a solid component (eggs) radiolabelled.12,13 Although other meals are used, standardising the test meal and establishing a normal range for gastric emptying of that meal are essential. Blood glucose levels should be below 15 mmol/L during measurement, as acute hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying.13

Management of gastroparesis

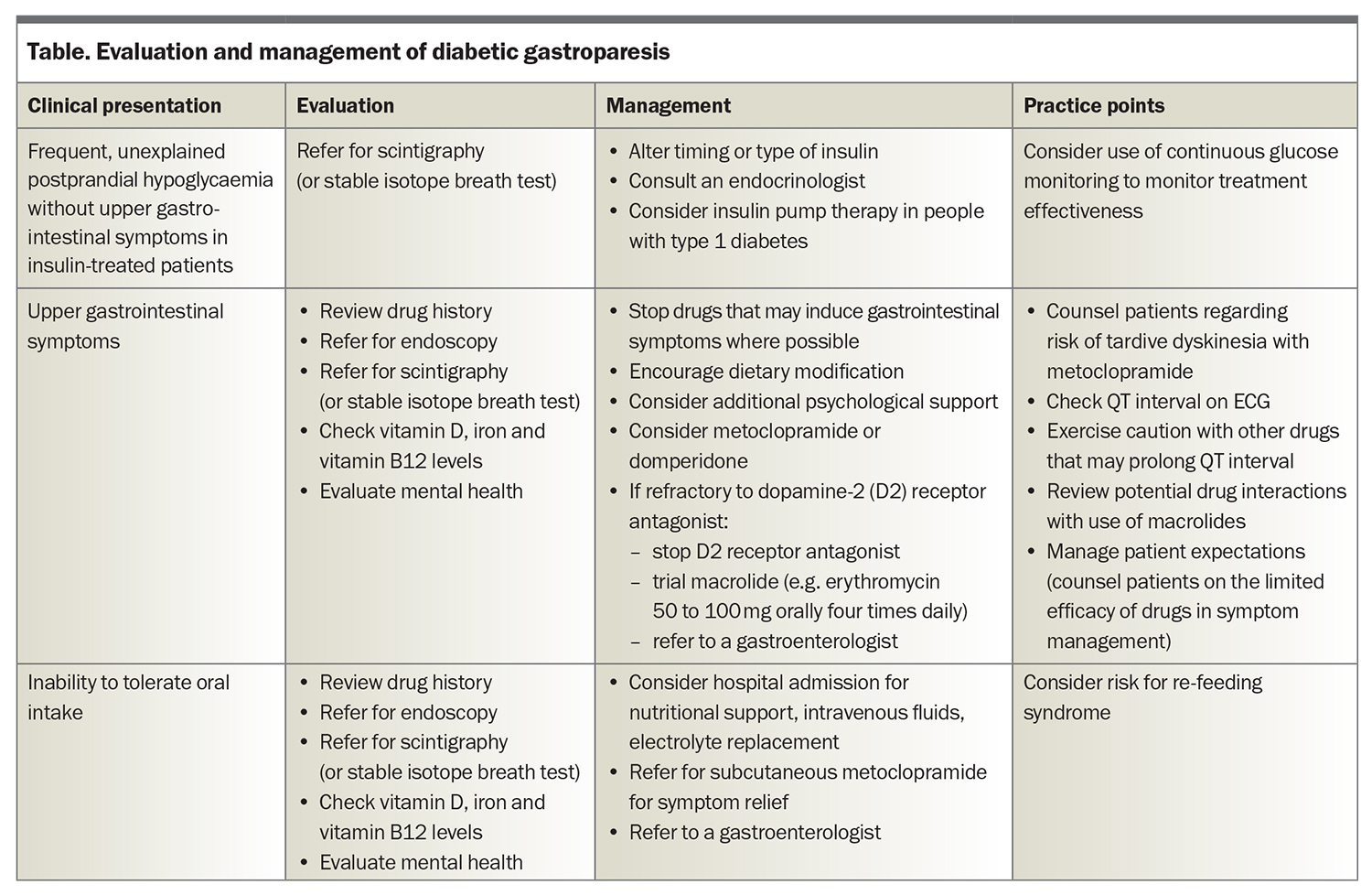

Management of diabetic gastroparesis often requires a multidisciplinary team, including an endocrinologist, a gastroenterologist, a dietitian and a psychologist, in addition to the GP. Evaluation and management of common clinical presentations are summarised in the Table.

Dietary management

Patients with diabetic gastroparesis may be advised to consume a small particle diet to help alleviate symptoms. This may require mashing food (e.g. potato) into a small particle size using a fork and excluding foods that have peels, husks (e.g. corn, peas, tomato, cabbage) or membranes (e.g. oranges), as well as fibrous food (e.g. asparagus, leek), seeds, grains, pasta, rice, meat, cheese slices and white fresh bread. A small particle diet is, accordingly, highly restrictive. Moreover, there is little evidence that it improves symptoms of gastroparesis.14 Not surprisingly, such a diet is also often not sustainable for long-term management and may be associated with nutritional deficiencies. Other interventions that can potentially improve symptoms include minimising the fat content of meals and having more starchy, bland foods.15 However, dietary management alone does not typically lead to adequate symptom relief.

Optimising glycaemic control

Optimisation of glycaemic control is likely helpful in both the short- and long-term management of symptoms, although sound prospective data are lacking. The timing or type of insulin to be administered may need to be modified in individuals with markedly delayed gastric emptying or in those with frequent postprandial hypoglycaemia. This is often done with the support of an endocrinologist and the use of continuous glucose monitoring, with low glucose alarms. Current hybrid closed-loop insulin pump systems do not account for delayed gastric emptying; however, in a recent small case series (n=7), use of this technology in individuals with gastroparesis was associated with an improvement in time in euglycaemic range (3.9 to 10 mmol/L) from 26 to 58% without increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia.16

Mental health management

Diabetic gastroparesis is strongly associated with psychological distress and impaired quality of life.17 A mental health evaluation should be considered and psychological support may prove beneficial. There is little information to support the choice of pharmacotherapy, if indicated. Mirtazapine has been reported to improve symptoms of gastroparesis in an open-labelled, uncontrolled trial, but was poorly tolerated by participants.18

Pharmacological management

Dopamine-2 (D2) receptor antagonists (metoclopramide and domperidone) remain the first-line treatment for gastroparesis with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Although these drugs accelerate gastric emptying, the relationship between improvement in symptoms and gastric emptying is weak at best. Individuals managed with metoclopramide should be counselled about the rare (0.1% per 1000 patient-years), but potentially irreversible, adverse effect of tardive dyskinesia.19 Domperidone improves symptoms of gastroparesis to a comparable extent to metoclopramide and is associated with a lower risk of tardive dyskinesia due to reduced permeability across the blood brain barrier.20 Thus, domperidone may be a preferable option if available. As D2 receptor antagonists are associated with prolongation of the corrected QT interval on ECG, it is advisable to perform an ECG before and after initiating treatment.

Both metoclopramide and domperidone also have antiemetic properties. There is anecdotal evidence that self-administration of subcutaneous metoclopramide may be effective in the treatment of acute episodes of vomiting in patients with gastroparesis. Other antiemetic therapies (e.g. 5-HT3 antagonist, ondansetron) are used in the management of symptomatic gastroparesis, but evidence to support their efficacy is limited.

The macrolide antibiotics erythromycin, azithromycin and clarithromycin are also motilin-receptor agonists that accelerate gastric emptying and are used ‘off-label’ for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis.21 Although short-term use of these drugs accelerates gastric emptying, controlled trials are needed to determine their efficacy in improving upper gastrointestinal symptoms and accelerating gastric emptying in the longer term.22 Erythromycin is the best studied antibiotic for the management of gastroparesis; however, it has a high potential for drug interactions (e.g. with warfarin, atorvastatin, simvastatin) and should be used with caution in patients taking other medications.23,24

Complementary and alternative medicines

Herbal therapies such as rikkunshito, iberogast or traditional Chinese medicines cannot currently be recommended for treatment of diabetic gastroparesis.21,25 Acupuncture is often used to manage gastrointestinal disorders and showed potential in alleviating symptoms of gastroparesis in initial trials. However, a subsequent meta-analysis was indicative of low-certainty evidence for acupuncture in improving symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis.26

Invasive therapies

For individuals with gastroparesis refractory to pharmacological and nonpharmacological management, referral to a gastroenterologist is indicated. In a recent sham-controlled, randomised clinical trial of individuals with refractory gastroparesis, gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy (G-POEM) was associated with symptomatic improvement in 71% of participants compared with 22% who underwent the sham procedure.27 Gastric emptying is also accelerated following G-POEM.28 Intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin showed potential for improving symptoms associated with refractory gastroparesis in initial open-labelled clinical trials; however, two subsequent sham-controlled trials failed to demonstrate improvement in either symptoms or gastric emptying.29,30 The delivery of low-energy, high-frequency electrical pulses to the antrum (gastric electrical stimulation) can effectively treat vomiting in individuals with diabetes (irrespective of whether they have gastroparesis), but gastric emptying is not accelerated and overall quality of life may not be improved.31 Further studies are needed before gastric electrical stimulation is incorporated into routine clinical practice.

Conclusion

Management of diabetic gastroparesis is complex and usually necessitates a multidisciplinary team. It is now appreciated that the severity of delay in gastric emptying correlates poorly with symptoms. Delayed gastric emptying may impact glycaemic control and oral drug absorption adversely. Because of the heterogeneous nature of the underlying dysfunctions of diabetic gastroparesis, the efficacy of current empirical approaches to management is limited. Future therapy should ideally be more personalised and targeted at the relevant pathophysiology. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Jalleh: None. Professor Horowitz is on the scientific and clinical advisory board for, and has stock options in, Glyscend. Dr Jones has participated in the advisory board for Glyscend.

References

1. Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Wishart JM, et al. Relationships between oesophageal transit and solid and liquid gastric emptying in diabetes mellitus. Eur J Nucl Med 1991; 18: 229-234.

2. Horowitz M, Harding PE, Maddox AF, et al. Gastric and oesophageal emptying in patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1989; 32: 151-159.

3. Asghar S, Asghar S, Shahid S, et al. Gastroparesis-related symptoms in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: early detection, risk factors, and prevalence. Cureus 2023; 15: e35787.

4. Horowitz M, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Read NW. ‘Gastric’ hypoglycaemia-an important concept in diabetes management. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2006; 18: 405-407.

5. Pfeiffer RF, Isaacson SH, Pahwa R. Clinical implications of gastric complications on levodopa treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020; 76: 63-71.

6. Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Can symptoms discriminate among those with delayed or normal gastric emptying in dysmotility-like dyspepsia? Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 1422-1428.

7. Watson LE, Xie C, Wang X, et al. Gastric emptying in patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes compared with young and older control subjects without diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: 3311-3319.

8. Grover M, Farrugia G, Lurken MS, et al. Cellular changes in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2011; 140: 1575-1585.

9. Amjad W, Qureshi W, Singh RR, Richter S. Nutritional deficiencies and predictors

of mortality in diabetic and nondiabetic gastroparesis. Ann Gastroenterol 2021; 34: 788-795.

10. Bi D, Choi C, League J, et al. Food residue during esophagogastroduodenoscopy is commonly encountered and is not pathognomonic of delayed gastric emptying. Dig Dis Sci 2021; 66: 3951-3959.

11. Jalleh RJ, Jones KL, Rayner CK, et al. Normal and disordered gastric emptying

in diabetes: recent insights into (patho)physiology, management and impact on glycaemic control. Diabetologia 2022; 65: 1981-1993.

12. Schol J, Wauters L, Dickman R, et al. United European Gastroenterology (UEG) and European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM) consensus on gastroparesis. United European Gastroenterol J 2021; 9: 883-884.

13. Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med Technol 2008; 36: 44-54.

14. Olausson EA, Storsrud S, Grundin H, et al. A small particle size diet reduces upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 375-385.

15. Eseonu D, Su T, Lee K, et al. Dietary interventions for gastroparesis: a systematic review. Adv Nutr 2022; 13: 1715-1724.

16. Daly A, Hartnell S, Boughton CK, Evans M. Hybrid closed-loop to manage gastroparesis in people with type 1 diabetes: a case series. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2021; 15: 1216-1223.

17. Woodhouse S, Hebbard G, Knowles SR. Psychological controversies in gastroparesis: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 1298-1309.

18. Malamood M, Roberts A, Kataria R, et al. Mirtazapine for symptom control in refractory gastroparesis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017; 11: 1035-1041.

19. Al-Saffar A, Lennernas H, Hellstrom PM. Gastroparesis, metoclopramide, and tardive dyskinesia: risk revisited. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019; 31: e13617.

20. Tendulkar P, Kant R, Rana S, et al. Efficacy of pro-kinetic agents in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with gastroparesis using lactulose hydrogen breath testing: a randomized trial. Cureus 2022; 14: e20990.

21. Camilleri M, Kuo B, Nguyen L, et al. ACG clinical guideline: gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2022; 117: 1197-1220.

22. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 259-263.

23. Dhir R, Richter JE. Erythromycin in the short- and long-term control of dyspepsia symptoms in patients with gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 38: 237-242.

24. Camilleri M, Atieh J. New developments in prokinetic therapy for gastric motility disorders. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 711500.

25. Zhang YX, Zhang YJ, Miao RY, et al. Effectiveness and safety of traditional Chinese medicine decoction for diabetic gastroparesis: a network meta-analysis. World J Diabetes 2023; 14: 313-342.

26. Kim KH, Lee MS, Choi TY, Kim TH. Acupuncture for symptomatic gastroparesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 12: CD009676.

27. Martinek J, Hustak R, Mares J, et al. Endoscopic pyloromyotomy for the treatment of severe and refractory gastroparesis: a pilot, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Gut 2022; 71: 2170-2178.

28. Vosoughi K, Ichkhanian Y, Benias P, et al. Gastric per-oral endoscopic myotomy (G-POEM) for refractory gastroparesis: results from an international prospective trial. Gut 2022; 71: 25-33.

29. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 26: 1251-1258.

30. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 416-423.

31. Ducrotte P, Coffin B, Bonaz B, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation reduces refractory vomiting in a randomized crossover trial. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 506-514.