Capturing the fracture: nutrition to support bone health in older adults

Age-related bone changes in older adults may not be apparent until an event such as a fracture occurs. Adequate nutritional intake and other lifestyle factors contribute to good bone health. Intake of the recommended servings of dairy foods per day in older adults living in residential aged care was found to reduce fractures and falls.

- Individuals may not be aware of age-related bone changes until an event such as a fracture occurs.

- Calcium and vitamin D are essential for bone metabolism. Other nutrients that support bone health include vitamin K, magnesium and zinc.

- Increased calcium intake combined with adequate vitamin D is associated with reduced fractures in older adults living in care homes who have low calcium intakes and vitamin D deficiency.

- An intake of at least 3.5 servings of dairy foods per day was associated with a reduction in fractures and falls and the prevention of weight loss, muscle loss at the arms and legs, and decline in nutritional status in older adults living in residential aged care.

- Older adults in the community with calcium intakes below the recommended level and comorbidities may potentially benefit from consuming the recommended servings of dairy foods, although research has not been conducted in this area.

- Vitamin D supplementation can be considered in patients who are unable to obtain safe sunlight exposure.

Bone is a dynamic tissue with potentially detrimental age-related changes occurring over a long period of time. These changes are often silent, until, for example, a fracture occurs. Many lifestyle factors contribute to bone health, including positive factors such as weight bearing and resistance exercise and adequate nutritional intake, and negative factors such as cigarette smoking and caffeine and alcohol intakes. Calcium and vitamin D are essential for bone metabolism, and there are several other nutrients that also contribute to good bone health.

What does good bone health mean?

For older adults, good bone health represents a way to reduce or slow bone loss. Unless a patient has experienced an osteoporotic fracture or is at high fracture risk (e.g. low bone density or additional risk factors such as long-term glucocorticoid use), they are not eligible to receive PBS subsidised osteoporosis medications so may not be concerned about their bone health. This article discusses ways that older adults can support their bone health from a nutritional perspective.

Calcium and protein

Calcium is the major nutrient that optimises bone health and is necessary for bone maintenance as well as neuromuscular and cardiac functions. Low calcium intake is associated with osteoporosis, which increases fracture risk.1 Increased calcium intake, combined with adequate vitamin D, is associated with reduced fractures in older adults in care homes with low calcium intakes (~500 mg per day) and vitamin D deficiency (~35 nmol/L).2 The daily calcium requirement for older men (>70 years) and women (>50 years) is 1300 mg per day and the daily calcium requirement for men between 51 and 70 years of age is 1000 mg per day.1 In terms of food, this is equivalent to four servings per day of dairy foods for women aged 50 years and older and 3.5 servings per day for men aged 70 years and older . The number of servings is higher for women because of their greater fracture risk.1 One serving of dairy foods equals one glass of milk (250 mL), two slices of cheese (40 g) or 200 g of yoghurt (slightly more than a regular small tub). Nondairy sources of calcium include almonds with skin (100 g), pink salmon with bones (100 g), sardines (60 g) and tofu (100 g).3

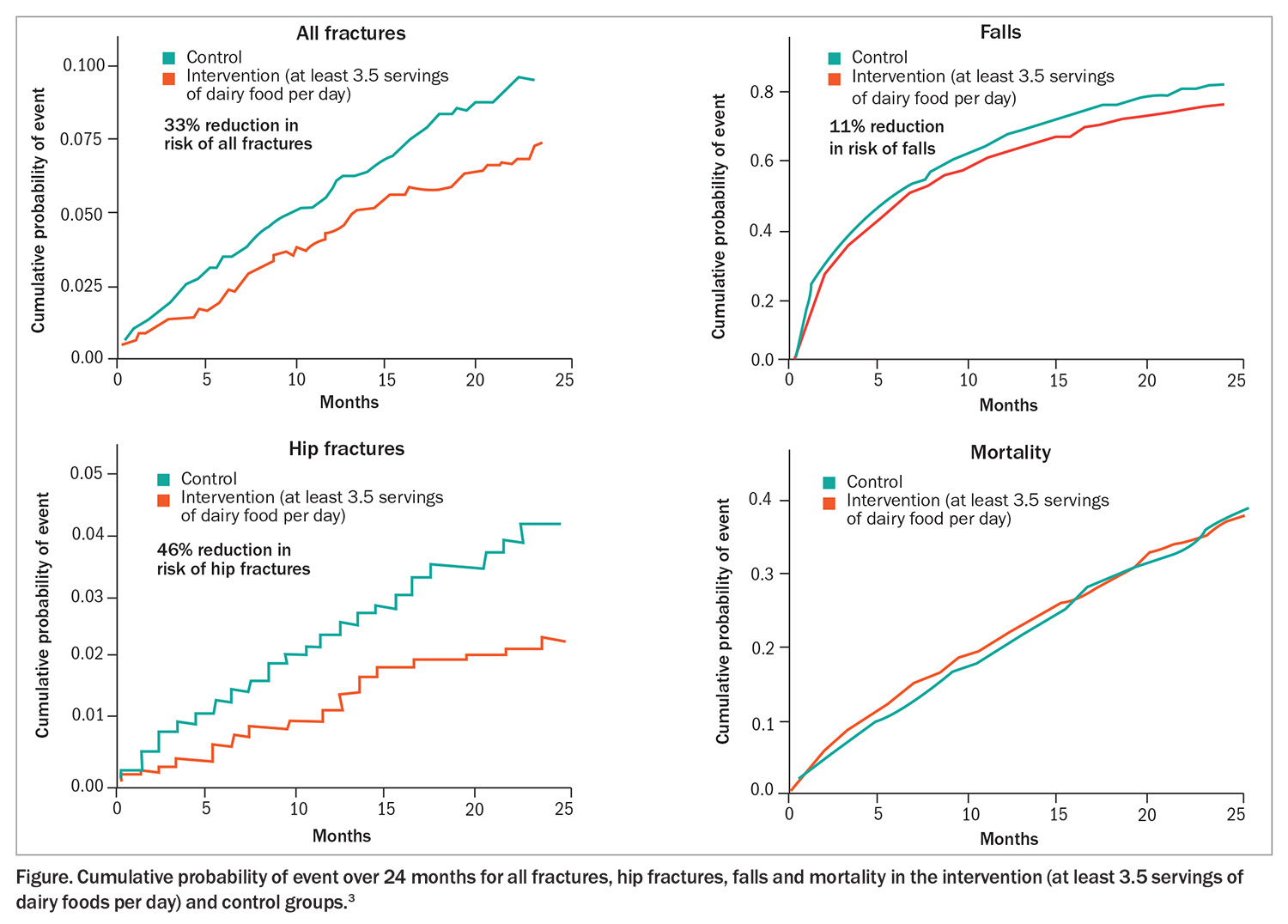

Research in older adults living in residential aged care in Australia demonstrates that an intake of at least 3.5 servings of dairy foods per day was associated with a 33% reduction in all fractures and a 46% reduction in hip fractures, an 11% reduction in falls (Figure), and prevention of weight loss, muscle loss at the arms and legs and decline in nutritional status.3,4 The enhanced dairy intake enabled residents to achieve the estimated average requirement for calcium (1100 mg per day) and an average protein intake (1.1 g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day) that was slightly higher than the Australian recommended levels of about 1 g of protein per kilogram of body weight.3

This study demonstrated that fracture reduction can be achieved in older adults with inadequate intakes of calcium (consuming about 600 mg per day) and protein (consuming about 0.8 g of protein per kilogram of body weight).3 The reduction of fractures may be related to the direct skeletal benefits of adequate calcium intake, such as maintenance of bone mineral density, and the indirect skeletal benefits, such as maintenance of bone resorption rates.3 Falls were reduced by 11% with the intervention, which may relate to the increased protein intake as appendicular muscle mass was maintained in those consuming the higher dairy intake, whereas loss of appendicular muscle mass was observed in the controls.3

Although there have been no similar research studies in the community, if calcium and protein intakes of older patients are below the recommended levels to the same degree as those in this study, and they have similar levels of comorbidities (about 10 medical conditions), they too may potentially benefit from achieving the recommended intake for foods from the dairy food group.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is needed to enhance the absorption of calcium by the small intestine for the maintenance of serum calcium concentrations. It can be produced from sunlight exposure and is found in a limited number of foods such as salmon and sardines.1

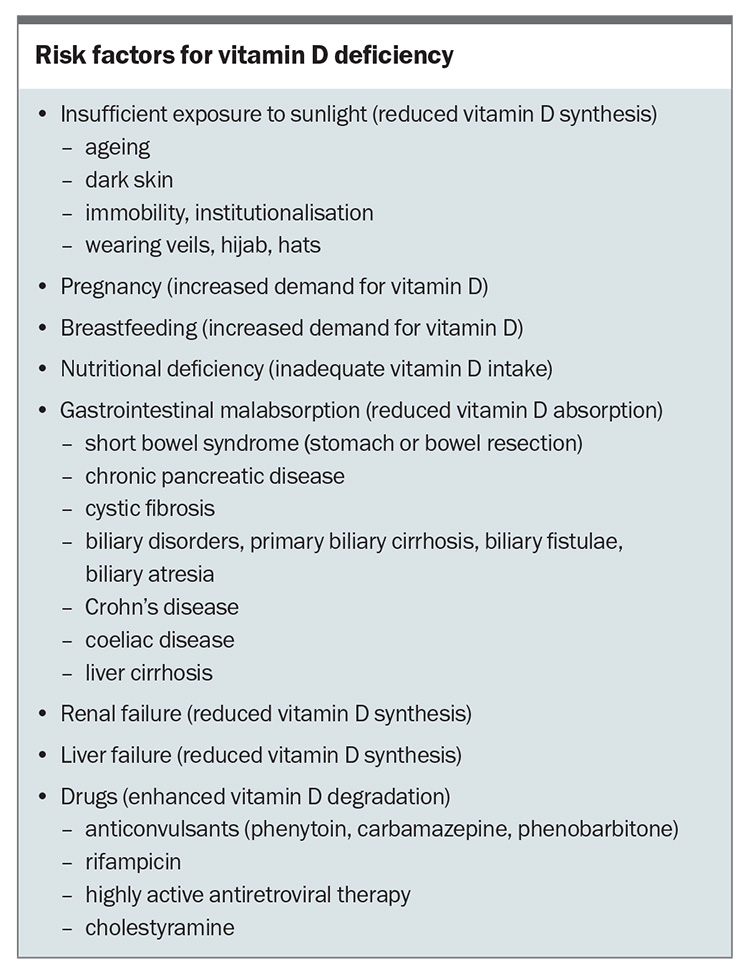

A key feature of this study in aged care was that these older adults were vitamin D replete (serum levels >50 nmol/L) with mean serum 25(OH)D levels of more than 70 nmol/L.3 The vitamin D status of patients can be assessed by a simple blood test, which is usually only indicated in high-risk individuals. If regular lifestyle habits (e.g. gardening and walking) are carried out, then patients may maintain vitamin D status through sunlight exposure. However, if there are confounding factors (e.g. reduced sunlight exposure because of chronic illness or if sunlight is considered unsafe due to skin cancers) then it may be worth suggesting supplementation (most commercially available vitamin D supplements contain 500 to 1000 IU of the vitamin, with some including calcium) if safe sunlight exposure is not possible. Dietary sources of vitamin D in Australia are not sufficient to maintain adequate serum vitamin D levels.5 Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency are shown in the Box.

Other nutrients that support bone health

Other nutrients that support bone health include vitamin K, magnesium and zinc; however, the antifracture efficacy associated with consumption of these nutrients has not been definitively demonstrated.6-8 The major food source for vitamin K is green leafy vegetables, the major food sources for magnesium are dairy, legumes and nuts, and the major food sources for zinc are meat, seafood and dairy. Therefore, encouraging food consumption in line with the Australian guidelines, while benefitting many aspects of health, also supports good bone health. For example, consuming one cup of green leafy vegetables (e.g. spinach, broccoli, lettuce, kale or cabbage), the recommended number of dairy servings (see above) and meeting the requirement of two servings daily (2.5 for men) from the meat food group (e.g. meat, poultry, seafood, eggs or legumes) would provide adequate nutrients to support optimal muscle and bone health.

Dietary patterns that include seafood, wholegrains, dairy, fruit and vegetables are associated with reduced risk of hip fracture in Swedish women who were followed up for 25 years.9 These dietary patterns also provide nutrients to support bone health.

Conclusion

The antifracture efficacy associated with a healthy diet is mainly derived from prospective and cross-sectional studies. In contrast, reduced risk of fractures in high-risk older adults has been demonstrated when high-calcium and high-protein dairy foods were consumed at recommended levels. The reduced fracture risk may be related to the skeletal and muscular benefits of adequate calcium and protein intakes. The described study showed a simple and cost-saving solution to reduce fracture risk in older adults at high risk of fractures and may potentially be of benefit to patients seen on a regular basis.3,10 ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Iuliano has received grants or contracts from the Bone Health Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Victorian Medical Research Acceleration Fund; lecture fees from Abbott, Dairy Australia, European Milk Forum, Global Dairy Platform, Maggie Beer Foundation, Nestle, Northern Ireland Dairy Council and South African Dairy; support for attending meetings from the European Milk Forum; and has a leadership or fiduciary role in the Australian Government National Aged Care Advisory Council.

References

1. Australian Government. Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand. Canberra: Australian Government; 1991. Available online at: https://www.nrv.gov.au (accessed May 2025).

2. Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1637-1642.

3. Iuliano S, Poon S, Robbins J, et al. Effect of dietary sources of calcium and protein on hip fractures and falls in older adults in residential care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021; 375: n2364.

4. Iuliano S, Poon S, Robbins J, Wang X, Bui M, Seeman E. Provision of high protein foods slows the age-related decline in nutritional status in aged care residents: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Nutr Health Aging 2023; 27: 166-171.

5. Iuliano-Burns S, Wang XF, Ayton J, Jones G, Seeman E. Skeletal and hormonal responses to sunlight deprivation in Antarctic expeditioners. Osteoporos Int 2009; 20: 1523-1528.

6. Mott A, Bradley T, Wright K, et al. Effect of vitamin K on bone mineral density and fractures in adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 2019; 30: 1543-1559.

7. Groenendijk I, van Delft M, Versloot P, van Loon LJC, de Groot L. Impact of magnesium on bone health in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone 2022; 154: 116233.

8. Ceylan MN, Akdas S, Yazihan N. The effects of zinc supplementation on C-reactive protein and inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis and systematical review. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2021; 41: 81-101.

9. Warensjo Lemming E, Byberg L, Melhus H, Wolk A, Michaelsson K. Long-term a posteriori dietary patterns and risk of hip fractures in a cohort of women. Eur J Epidemiol 2017; 32: 605-616.

10. Baek Y, Iuliano S, Robbins J, Poon S, Seeman E, Ademi Z. Reducing hip and non-vertebral fractures in institutionalised older adults by restoring inadequate intakes of protein and calcium is cost-saving. Age Ageing 2023; 52: afad114.