Postmenopausal osteoporosis: bridging the treatment gap

Osteoporosis affects many women in Australia and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality. An evidence treatment gap still exists; therefore, efforts should be made to bridge this gap by identifying women at high risk of fracture and initiating suitable treatments without delay.

- Osteoporosis and osteopenia affect over half of all women aged over 50 years.

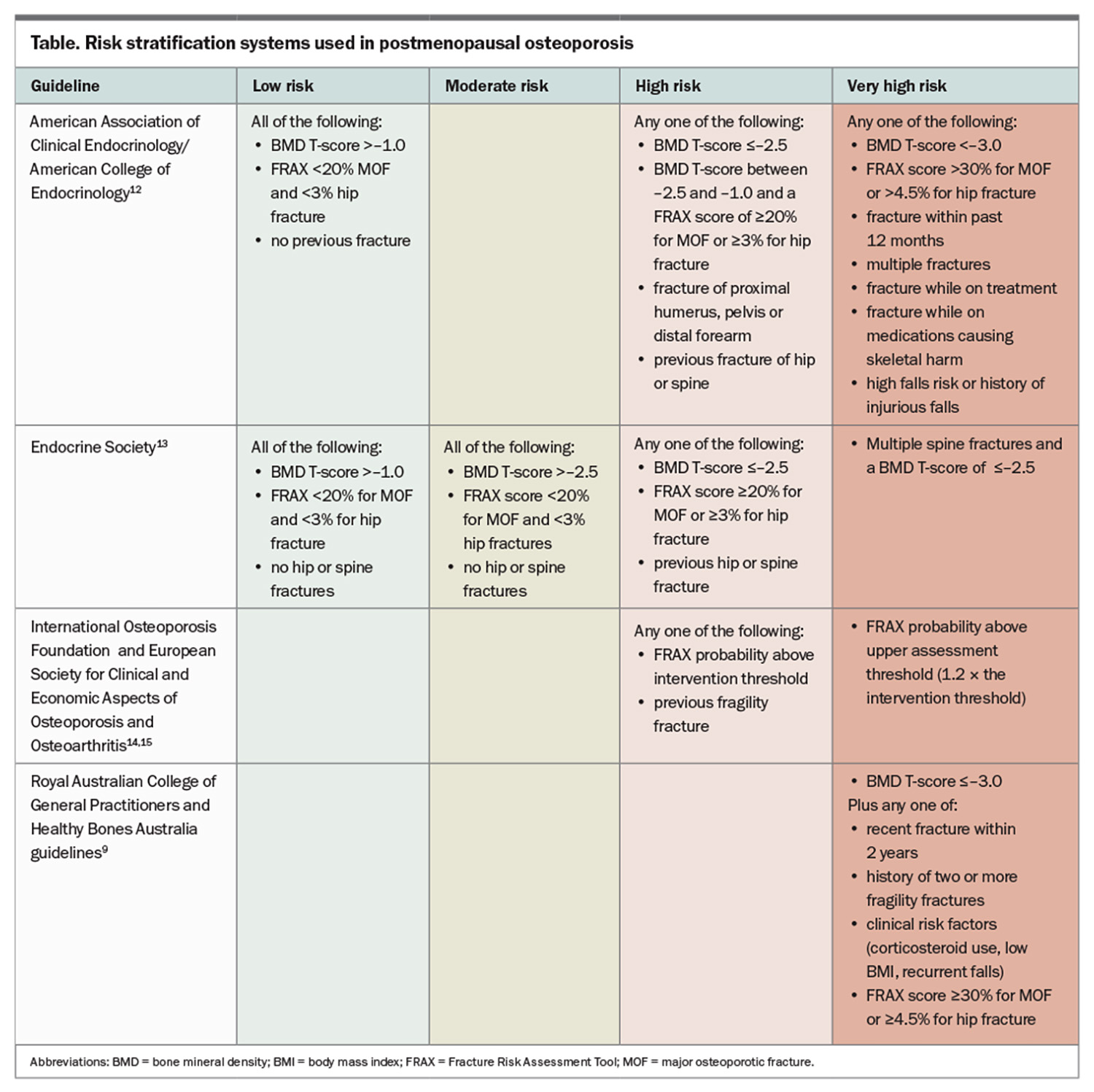

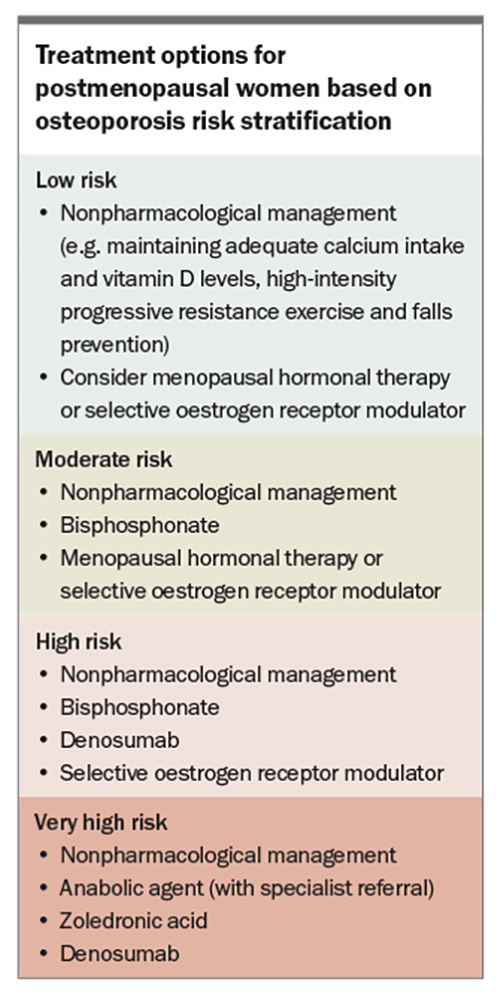

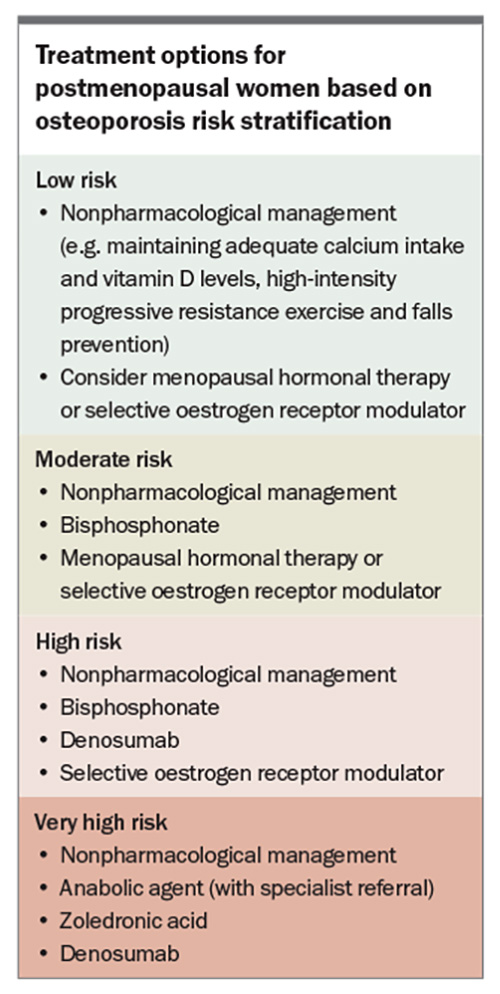

- Risk-stratification systems are recommended to identify patients who require treatment and to guide the type of therapy.

- The most common first-line therapies for osteoporosis are bisphosphonates and denosumab.

- In very high-risk patients, anabolic agents can be considered as first-line therapy, under specialist guidance.

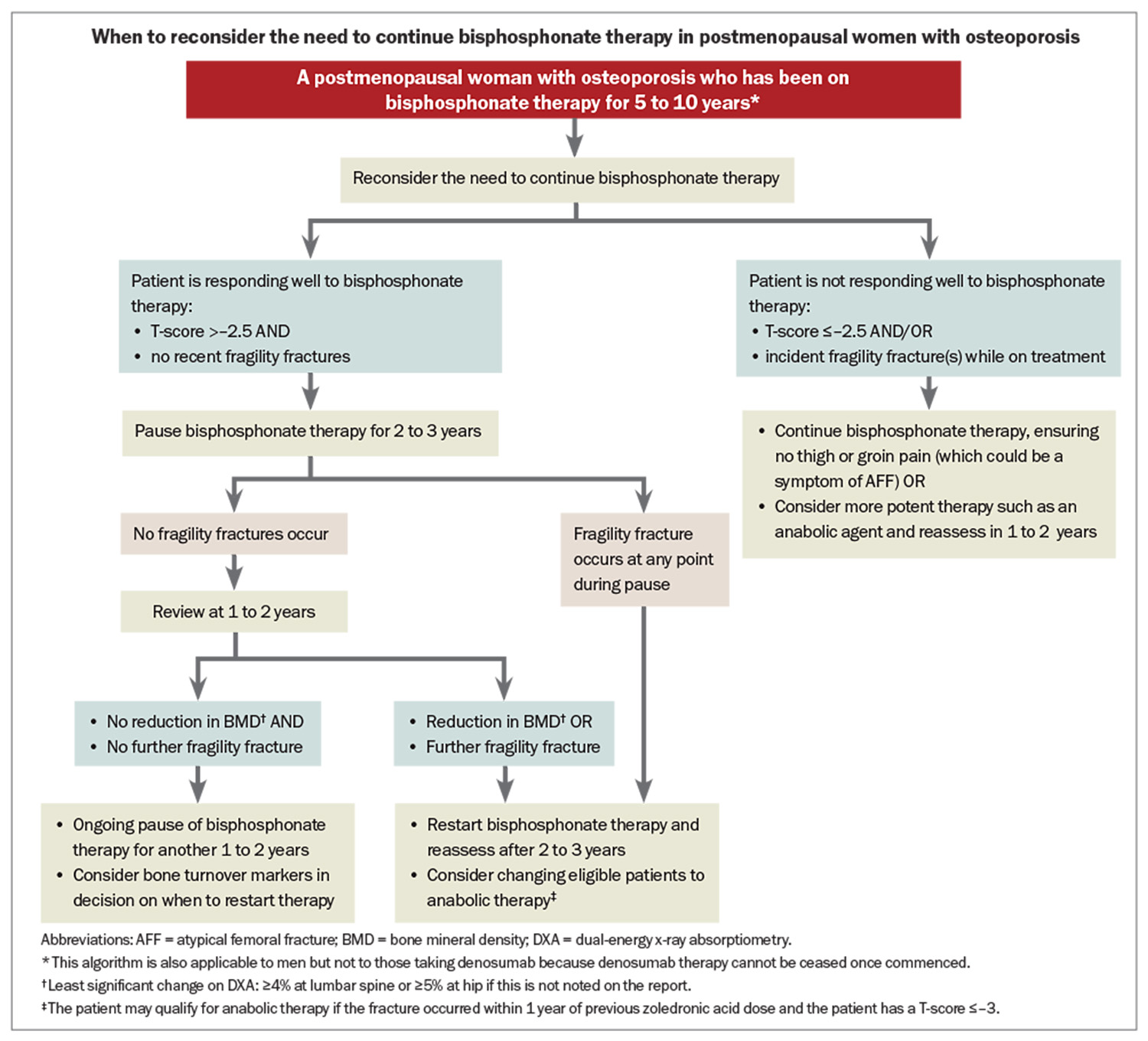

- In patients treated with bisphosphonates for 5 to 10 years, with bone mineral density (BMD) T-scores of more than –2.5 and with no recent fractures, a treatment pause should be considered, with ongoing evaluation every one to three years.

- Denosumab therapy should not be paused because it is associated with a rapid loss of BMD and sometimes multiple vertebral fractures. Specialist referral is recommended in patients in whom denosumab needs to be stopped.

About 50% of women aged 50 to 54 years have osteoporosis or osteopenia and this increases to over 90% in women aged 80 years or older.1 The lifetime risk of fracture for a woman aged 60 years is as high as 44%, and in the 12 months following an initial fracture, one in 10 will sustain another fracture.2-4 Despite global awareness of osteoporosis and the wide availability of treatments, there are significant gaps in care, with failure to screen women for osteoporosis, failure to identify a first fracture as osteoporosis and low treatment rates.5-7 Recent data suggest only about one-third of women in Australia with osteoporosis or fractures receive treatment, and adherence is low.8

Osteoporotic fractures are fragility fractures, meaning they occur with minimal or no trauma (usually defined as falling from standing height or less); thus, when fractures are mentioned in this article, it is implied that we are referring to fragility fractures. In addition, although this article is about managing postmenopausal women, many of the principles apply to men over 50 years of age who are also affected by the burden of osteoporosis, but it should be noted that minimal data are available for this group.

Definition of osteoporosis

A diagnosis of osteoporosis should be considered in women aged 50 years and older with any of the following: a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of –2.5 or less at the lumbar spine, hip or radius on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), a prior minimal trauma fracture or radiological evidence of a vertebral compression fracture (>20% loss of height) without known trauma.

Investigations

In most postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, diagnosis consists of medical history taking, examination and DXA. Basic laboratory assessment, including biochemistry and measurement of renal function, calcium levels and vitamin D levels, should be performed in most women, as the results of these assessments will guide treatment. A thoracolumbar x-ray may also be needed to diagnose vertebral fractures, the presence of which may change management.

A more thorough screen for secondary causes of osteoporosis should be performed if there is clinical suspicion based on history (e.g. early-onset fractures, premature ovarian insufficiency, symptoms of associated conditions such as malabsorption or fractures despite treatment), examination or BMD Z-scores of –2 or less (suggesting BMD is lower than expected for sex and age).9 Some studies have shown cost effectiveness of performing screening tests, such as measurement of parathyroid hormone levels and thyroid function at baseline, on all women.10,11 These tests, along with liver function tests, are recommended to be considered as part of a secondary screen, which may also include coeliac serology, myeloma screening, urinary calcium, tryptase and assessment for cortisol overproduction. Gonadal studies are not necessary as these women are, by definition, postmenopausal. When applying the principles of this article to men with osteoporosis, testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin and luteinising hormone level testing is indicated.

Selecting patients for treatment

Risk-stratification systems are recommended to identify high-risk patients who require treatment and to guide the type of therapy. Patients can be divided into low, moderate, high and very high subgroups (Table and Box).9,12-15 In the case of low-risk patients, conservative, nonpharmacological management can be considered, with BMD monitoring after 24 months. High-risk patients include those with previous fractures, particularly of the hip or spine, a high 10-year probability of fracture (using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool [FRAX]; high risk if FRAX score is ≥3% for hip fractures or ≥20% for major osteoporotic fractures) or a BMD T-score of –2.5 or less. There is a general consensus that these high-risk patients should be treated with pharmacotherapy. According to recently published Australian guidelines, very high-risk individuals are those with BMD T-scores of –3.0 or less plus any one of the following:9

- fragility fracture within the past two years

- history of two or more fragility fractures

- corticosteroid use, low body mass index or recurrent falls

- FRAX risk score of 30% or more for major osteoporotic fractures or 4.5% or more for hip fracture.

Anabolic therapies, under specialist guidance, should be considered in this very high-risk group.

Nonpharmacological management

Nonpharmacological management applies to all risk categories. It includes avoiding toxins to bones (e.g. smoking, three or more standard serves of alcohol daily), maintaining adequate calcium intake and vitamin D levels, high-intensity progressive resistance exercise and falls prevention.

The recommended calcium intake for postmenopausal women in Australia is 1300 mg daily, ideally via dietary means. If this is not possible, supplementation with up to 600 mg daily, typically with calcium carbonate or calcium citrate depending on patient tolerability, is recommended.9,16 Vitamin D3 levels should be maintained at 50 to 100 nmol/L (note that levels >125 nmol/L may be detrimental) with supplementation as needed.17 Repeat testing may be performed after three months to ensure sufficient levels and, once these are achieved, maintenance supplementation should continue, generally at a lower dose than that needed to raise the level into the therapeutic range.

Progressive resistance training can increase BMD, prevent fractures and reduce falls, which is the largest contributor to fractures.18,19 Women should therefore be encouraged to undertake progressive resistance training at least twice per week and weightbearing impact exercises most days per week, as well as balance training activities.9

Pharmacological management

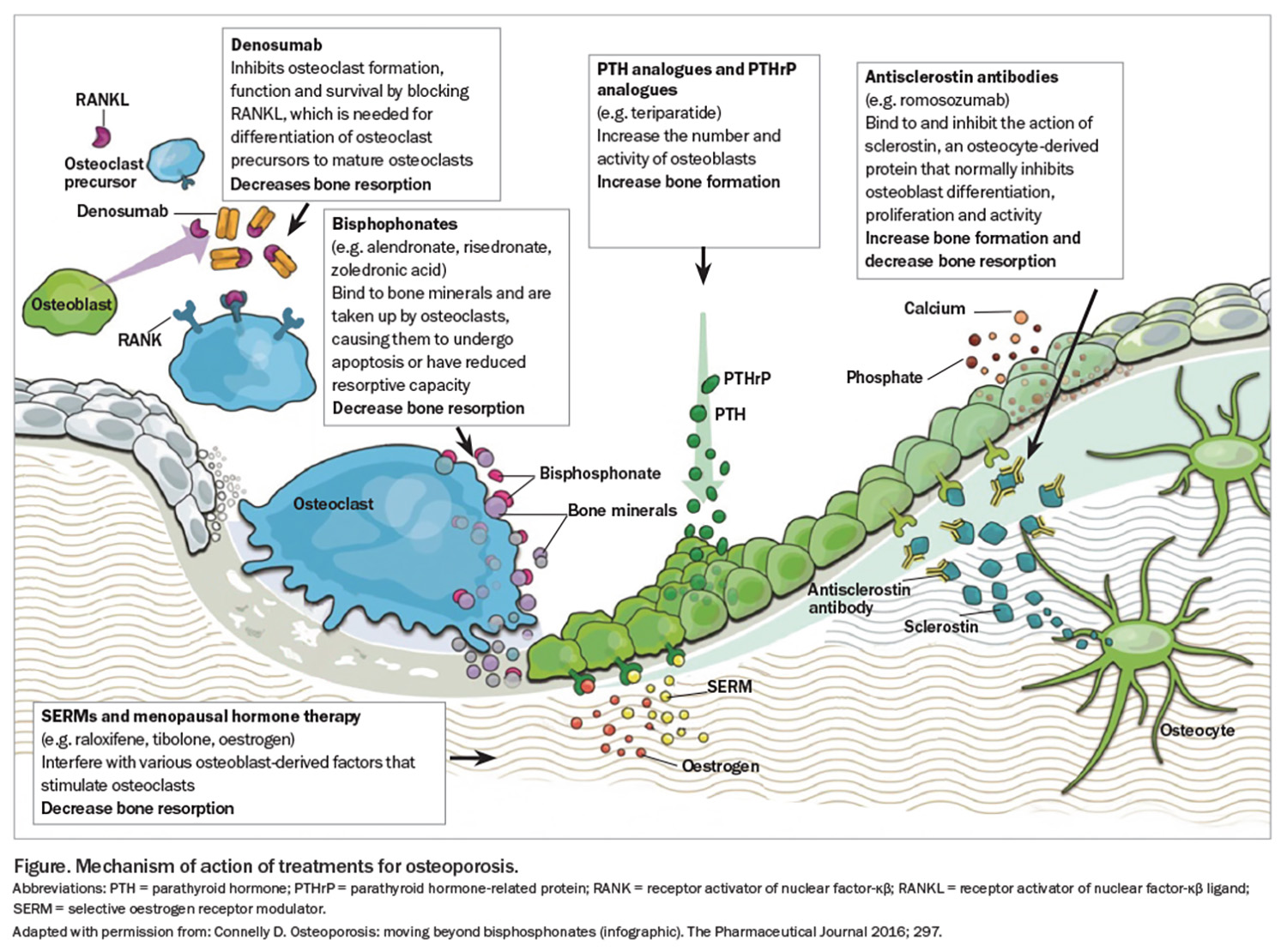

A summary of the available pharmacological therapies and how they work on the bone is shown in the Figure.

Antiresorptive agents

Bisphosphonates

Oral bisphosphonates are the most prescribed medications worldwide for osteoporosis; however, in Australia, their use has steadily declined over the past decade, being superseded by denosumab.20 Bisphosphonates attach to hydroxyapatite binding sites on the bone surface, inhibiting osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, and reducing osteoclast numbers. Oral bisphosphonates are usually taken once per week, while fasting (with the exception of Actonel-EC, which can be taken with or without food). Patients are advised to remain upright for 30 minutes to ensure delivery to the stomach and minimise gastrointestinal side effects. Oral bisphosphonates reduce nonvertebral fractures by 15 to 20% and vertebral fractures by 40%.21 Side effects are generally mild but include oesophagitis and oesophageal ulceration, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, constipation or diarrhoea, renal impairment, musculoskeletal pain and, rarely, osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and atypical femoral fractures (AFFs). Adherence can be problematic, with studies indicating adherence to oral bisphosphonate at 1 year as low as 17%.22 Oral bisphosphonates are generally not recommended in people with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance rate <30 to 35 mL/min), although they may be used in this population at a reduced dosing frequency under specialist guidance.

The main intravenous bisphosphonate used for treating osteoporosis in Australia is zoledronic acid, typically 5 mg annually, but this can be protracted to 18 monthly. Zoledronic acid reduces nonvertebral fractures by 20% and vertebral fractures by 60%.21 Side effects, such as an acute phase reaction, may occur in up to 40% of patients, typically appearing within 24 to 48 hours.23 Pretreatment with paracetamol or glucocorticoids (prednisolone 25 mg on the day before, the day of and the day after) may minimise this adverse effect, and the reaction usually decreases with subsequent doses.24,25 It is our practice to prescribe paracetamol routinely before the initial dose and ongoing for the next 48 hours as needed. Other less common side effects include injection site reactions, musculoskeletal pain, uveitis, elevated parathyroid hormone levels, renal impairment, gastrointestinal symptoms and, rarely, ONJ and AFFs. Zoledronic acid is generally not recommended for people with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance rate <30 to 35 mL/min).

Australian guidelines suggest using bisphosphonates for five to 10 years in patients who have responded positively to treatment (BMD T-score >–2.5 and no recent fractures), at which point a plateau can be seen in the BMD response, and a treatment pause should be considered.9 Treatment should be continued in patients with BMD T-scores of –2.5 or below or incident fractures during treatment. In both instances, whether treatment is continued or paused, the need for treatment and choice of therapy should be reconsidered every one to three years (see Flowchart).

Denosumab

Denosumab is a monocloncal antibody to receptor activator of nuclear factor-κβ ligand and leads to profound but reversible suppression of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Administered as a 60 mg subcutaneous injection every six months, denosumab reduces nonvertebral fractures by 20%, and vertebral fractures by almost 70%.21 The main side effects of denosumab are injection site reactions, musculoskeletal pain, hypocalcaemia (especially in people with reduced renal function or vitamin D deficiency), elevated parathyroid hormone level (especially in the first few months after injection), a small increase in the risk of cellulitis and, rarely, ONJ and AFFs. Denosumab is approved for use in patients with chronic kidney disease, although caution should be advised because of the risk of hypocalcaemia in patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease.26 We recommend ensuring the vitamin D level is adequate before each dose. If there is a risk of hypocalcaemia, calcium supplementation (about 1000 mg daily) for two days before until two weeks after each dose is recommended, with monitoring of calcium levels in the first two weeks of initiating therapy.9,27

The effects of denosumab are fully reversible; suppression of bone resorption wanes and ceases about seven months after the last dose, and this is associated with a dramatic rise in bone resorption, associated with loss of BMD and multiple vertebral fractures in people who delay doses or stop taking denosumab.28 For this reason, denosumab should be given every six months, without delay of more than one to two weeks and, in most patients, continued lifelong. The use of denosumab diaries or GP patient recall systems may avoid the accidental omission of therapy.

Although safety data from the Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis Every 6 Months (FREEDOM) trial demonstrated safety of denosumab for up to 10 years, there is no suggestion that long-term denosumab use beyond that time is associated with harm.29 Nevertheless, until longer follow-up studies are available, our approach is to commence denosumab in older adults in whom lifelong treatment will be of shorter duration. If denosumab is the most suitable agent in a younger patient, counselling that this therapy will be lifelong is needed. In people who have started taking denosumab but do not want to continue, referral to a specialist for management is recommended. Studies using alternative antiosteoporosis medications to mitigate the loss of bone density that occurs after denosumab cessation are ongoing, with mixed results.30

Selective oestrogen receptor modulator: raloxifene

Raloxifene is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator, which binds oestrogen receptors in bone to inhibit bone resorption. Administered as an oral 60 mg tablet daily, raloxifene reduces vertebral fractures by 40%, but does not reduce nonvertebral or hip fractures.21 It is therefore a reasonable option in women with isolated low spine BMD or who are unable to tolerate other antiosteoporosis medications.8 Side effects include hot flushes, muscle spasm, oedema, increased risk of venous thromboembolic events and increased stroke mortality, although the incidence of stroke is not increased.31 Raloxifene is contraindicated in women with a previous history of venous thromboembolic events, and caution should be exercised in women at risk of, or with a prior history of, stroke.

Menopausal hormone therapy

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), with either oestrogen alone (in hysterectomised women) or oestrogen and a progestogen (in women with an intact uterus) reduces bone resorption. Topical and oral MHT have similar effects on BMD in postmenopausal women, and although there appears to be a positive association between oestrogen dose and BMD increment, the optimal dose for bone preservation is unclear.32 Starting MHT early after the onset of menopause has a more positive effect on BMD compared with later use. MHT reduces nonvertebral, vertebral and hip fractures by about 20 to 35%.21,33 The major side effects of MHT include nausea, migraine, breast tenderness, oedema, vaginal bleeding and, for oral MHT, thromboembolic events and gallbladder disease. Combined MHT (including a progestogen) is associated with a small increase in the risk of breast cancer – about two additional cases per 50 to 70 women treated for 10 years, which is less than the increased risk associated with excessive alcohol use or obesity.34 Evidence among women treated with oestrogen-only MHT is more mixed, with studies showing a slight increase or decrease in risk.34 There is evidence that MHT started early post menopause (within 10 years of menopause) and under the age of 60 years is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular events; however, if started later, this risk is increased.35 Therefore, MHT should be considered for osteoporosis in younger postmenopausal women, ideally soon after menopause, and particularly if other bothersome symptoms of menopause are present.9,36

Tibolone can be considered as an alternative to conventional MHT. Tibolone is a synthetic steroid, with metabolites that have oestrogenic, progestogenic and androgenic actions. Administered as an oral dose of 1.25 to 2.5 mg daily, it reduces nonvertebral fractures by 25% and vertebral fractures by 45%.21 Tibolone relieves vasomotor symptoms, can improve libido, and has similar contraindications and side effects to conventional MHT, with the important caution of increased risk of stroke, especially in women over 70 years of age. If the principles in this article are being used to treat osteoporosis in men, it must be noted that the consideration of SERMs and MHT are not applicable in men.

Anabolic agents

Anabolic osteoporosis medications actively increase bone formation. In Australia, two anabolic medications are available: teriparatide and romosozumab. These are indicated as primary therapy in postmenopausal women at very high risk of fracture (see Box), but are PBS subsidised only as secondary treatment, in the setting of a fracture on first-line therapy and with a BMD T-score of –3.0 or below (see PBS website for full details). Romosozumab has been recommended for the treatment of severe osteoporosis in the first-line setting by the PBAC; however, at the time of writing, it has not been listed on the PBS for this indication. Both teriparatide and romosozumab need to be privately funded if used as primary therapy. In most cases, patients who take anabolic therapy should be managed by a specialist, and this is also needed for PBS-subsidised treatment.

Teriparatide

Teriparatide comprises the first 34 amino acids of parathyroid hormone. Parathyroid hormone increases both bone resorption and formation and, when given as intermittent daily injections, the bone-forming properties predominate.37 Teriparatide is a daily, usually self-administered, subcutaneous injection that is TGA approved for 24 months of use, but only PBS subsidised for 18 months’ duration. Teriparatide reduces nonvertebral fractures by 40% and vertebral fractures by 70%.20 Typical side effects include injection site reactions, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, headache, hypercalcaemia and dizziness. Nighttime administration is advised. Teriparatide is contraindicated in patients with a history of bone malignancy or metastases, past history of skeletal radiotherapy, unexplained elevated alkaline phosphatase levels or Paget’s disease because of a theoretical risk of osteosarcoma. Increased risk of osteosarcoma has been reported in rats using teriparatide, but in humans the incidence for people using teriparatide is at or lower than the population incidence.38

Romosozumab

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits sclerostin, which acts to increase bone formation while also suppressing bone resorption.39 It is administered as monthly injections, usually by a healthcare professional, for 12 months. Romosozumab reduces nonvertebral fractures by 30% and vertebral fractures by 70%.21 Side effects include injection site reactions, headache, musculoskeletal pain, flushing, oedema and upper respiratory tract symptoms and, rarely, ONJ and AFFs.39 An association with cardiovascular disease has also been reported. The Alendronate-controlled Study to Determine the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in the Treatment of Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis (ARCH) trial compared romosozumab with alendronate and showed an increased risk of myocardial infarction (0.8% in romosozumab group vs 0.3% in alendronate group) and stroke (0.8% in romosozumab group vs 0.3% in alendronate group).40 This signal was not seen in placebo-controlled trials, but postmarketing TGA surveillance reported nine cardiovascular events as of November 2023.41 For this reason, romosozumab should not be used in patients with a history of myocardial infarction or stroke, and cardiovascular risk factors should be assessed and managed before commencement.

At completion of a course of anabolic therapy (18 to 24 months for teriparatide or 12 months for romosozumab), an antiresorptive medication must be administered as consolidation because the anabolic effects are reversible and would be lost if not consolidated. Options for consolidation therapy include a single dose of zoledronic acid, one to two years of oral bisphosphonates or denosumab ongoing.

Rare adverse effects of all antiresorptive agents

Two adverse effects that have received much attention over the past two decades are ONJ and AFF. All antiresorptive agents (bisphosphonates, denosumab, romosozumab) are associated with an increased relative risk of ONJ; however, the absolute risk remains low at doses and frequencies used for osteoporosis, estimated at one in 10,000 to less than one in 100,000.42 This risk is much higher in the setting of cancer patients in whom the doses of zoledronic acid and denosumab are much higher and more frequent. The major risk factor for ONJ is invasive dentoalveolar procedures, such as teeth extractions or dental implants; however, even in patients undergoing these procedures, the risk is estimated at less than 1%.43 Underlying dental disease, poor dental hygiene, chronic use of proton pump inhibitors, chemotherapy and glucocorticoid medications also increase the risk. In practice, clinicians should discuss the risk of ONJ with patients initiating antiresorptive therapy and encourage good oral hygiene (brushing twice daily and flossing daily). If there is concern about dental hygiene (mouth pain, bleeding or loose or broken teeth) or an invasive procedure is planned, dental review should be completed before initiating therapy, but routine dental examination is not required for all people.42 For patients who are already taking antiresorptive agents, Australian guidelines do not recommend ceasing bisphosphonates before invasive dental procedures because of their long half-life. Patients taking denosumab should have invasive dental procedures performed just before their next six-monthly dose is due (between four and six months after the preceding dose), if this is feasible.9

All bisphosphonates (and rarely denosumab) are associated with a small but definite risk of AFF. AFF is a non-comminuted transverse or oblique fracture of the subtrochanteric or femoral shaft region, typically with minimal or no trauma, and is defined by specific clinical and radiological criteria.44 Patients may present with a prodrome of groin, thigh, knee or hip pain, and the AFF may be unilateral or bilateral. AFFs are associated with continuous, prolonged use of antiresorptives, and are more prevalent in women of Asian ethnicity. After three to five years of bisphosphonate therapy, the risk of AFF is about 2.5 fractures per 10,000 person-years, increasing to 13.1 after eight or more years.45 The risk of AFF relates to continuous cumulative use of bisphosphonates, and the risk drops rapidly by about 70% per year of treatment discontinuation. In practice, women should be counselled about the risk of AFFs, and if thigh pain occurs during treatment, a bilateral plain x-ray of the entire femora, followed by MRI or bone scan if needed, can be used to diagnose AFF.44

Monitoring on treatment

Monitoring of patients on treatment is primarily clinical – assessment of interim fractures, side effects of medication and adherence. Pathology may include measurement of vitamin D levels, renal function and calcium levels, particularly in patients with, or at risk of, impaired renal function, which may necessitate a change in management. We suggest measuring vitamin D levels before each dose of denosumab or zoledronic acid because of the risk of hypocalcaemia with use of these agents. Bone turnover markers widely available in Australia include C-telopeptide, a marker of bone resorption, and procollagen type 1 N-propeptide (P1NP), a marker of bone formation. Antiresorptive medications (bisphosphonates and denosumab) typically lead to optimal bone turnover suppression as reflected by low C-telopeptide (ideally to values less than 200 mcg/L) and P1NP markers. Most women do not require routine testing of bone turnover markers. Circumstances where testing may be appropriate include if poor compliance to, or absorption of, oral bisphosphonates is suspected, in which case they will not be suppressed, or during a bisphosphonate treatment pause, whereby rising markers may be included, along with BMD and other clinical factors, especially fracture occurrence, in the decision to restart treatment.

Serial DXA can be performed one to two years after commencing therapy and depending on the indication. Serial DXA should be performed on the same machine to allow comparison to earlier scans. If performed on a different machine, limited comparisons can be made as to whether significant changes have occurred. The spine is the preferred site for assessing change, with the total hip recommended if the spine is inaccurate (for example, due to vertebral fractures or degenerative disease).46 Stable or increasing BMD is considered treatment success, whereas a reduction in BMD while on treatment should prompt consideration of compliance issues or secondary causes of osteoporosis.12 In women not treated, or during a treatment pause, serial DXA is important to assess for loss of BMD, which may prompt treatment (re)initiation.47

Conclusion

Osteoporosis affects many women in Australia and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality as women age. Appropriate management can improve BMD and reduce fractures. An evidence treatment gap still exists and, therefore, efforts should be made to bridge this with earlier treatment if indicated. With multiple treatments available in Australia, it is important to identify patients at high risk of fracture and initiate suitable treatment option(s) without delay. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Henry MJ, Pasco JA, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA. Prevalence of osteoporosis in Australian men and women: Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Med J Aust 2011; 195: 321-322.

2. Balasubramanian A, Zhang J, Chen L, et al. Risk of subsequent fracture after prior fracture among older women. Osteoporos Int 2019; 30: 79-92.

3. Hansen D, Pelizzari P, Pyenson B. Medicare cost of osteoporotic fractures - 2021 updated report. The clinical and cost burden of fractures associated with osteoporosis. Milliman Research Report For the National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2021.

4. Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22: 781-788.

5. Gillespie CW, Morin PE. Trends and disparities in osteoporosis screening among women in the United States, 2008-2014. Am J Med 2017; 130: 306-316.

6. Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, et al. SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos 2021; 16: 82.

7. Eisman J, Clapham S, Kehoe L, Australian BoneCare S. Osteoporosis prevalence and levels of treatment in primary care: the Australian BoneCare Study. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19: 1969-1975.

8. Alicia R Jones, Joanne E Enticott, Peter R Ebeling, et al. Geographic Variation in osteoporosis treatment in postmenopausal women: a 15-year longitudinal analysis, J Endoc Society 2024; 8(8). doi: https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvae127.

9. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Healthy Bones Australia. Osteoporosis management and fracture prevention in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age. 3nd edn.: RACGP; 2024.

10. Tannenbaum C, Clark J, Schwartzman K, et al. Yield of laboratory testing to identify secondary contributors to osteoporosis in otherwise healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 4431-4437.

11. Johnson K, Suriyaarachchi P, Kakkat M, et al. Yield and cost-effectiveness of laboratory testing to identify metabolic contributors to falls and fractures in older persons. Arch Osteoporos 2015; 10: 226.

12. Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, at al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists /American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis - 2020 update. Endocr Pract 2020; 26(Suppl 1): 1-46.

13. Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Eastell R. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: An Endocrine Society Guideline Update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105(3): dgaa048.

14. Kanis JA, Harvey NC, McCloskey E, et al. Algorithm for the management of patients at low, high and very high risk of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporosis International 2020; 31: 1-12.

15. Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2019; 30: 3-44.

16. National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2013.

17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Biomedical Results for Nutrients Canberra: ABS; 2011. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-biomedical-results-nutrients/2011-12 (accessed August 2024).

18. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 15: (2): CD007146

19. El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Charles MA, Dargent-Molina P. The effect of fall prevention exercise programmes on fall induced injuries in community dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013; 347: f6234.

20. Smith L, Wilson S. Trends in osteoporosis diagnosis and management in Australia. Arch Osteoporos 2022; 17(1): 97.

21. Barrionuevo P, Kapoor E, Asi N, et al. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women: a network meta-Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: 1623-1630.

22. Fatoye F, Smith P, Gebrye T, Yeowell G. Real-world persistence and adherence with oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e027049.

23. Reid IR, Gamble GD, Mesenbrink P, Lakatos P, Black DM. Characterization of and risk factors for the acute-phase response after zoledronic acid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 95: 4380-4387.

24. Silverman SL, Kriegman A, Goncalves J, Kianifard F, Carlson T, Leary E. Effect of acetaminophen and fluvastatin on post-dose symptoms following infusion of zoledronic acid. Osteoporos Int 2011; 22: 2337-2345.

25. Murdoch R, Mellar A, Horne AM, et al. Effect of a three-day course of dexamethasone on acute phase response following treatment with zoledronate: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 2023; 38: 631-638.

26. Bird ST, Smith ER, Gelperin K, et al. Severe hypocalcemia with denosumab among older female dialysis-dependent patients. JAMA. 2024; 331: 491-499.

27. Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 756-765.

28. Cosman F, Huang S, McDermott M, Cummings SR. Multiple vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: FREEDOM and FREEDOM Extension Trials Additional Post Hoc Analyses. J Bone Miner Res 2022; 3: 2112-2120.

29. Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017; 5: 513-523.

30. Tsourdi E, Zillikens MC, Meier C, et al. Fracture risk and management of discontinuation of denosumab therapy: a systematic review and position statement by ECTS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106: 264-281.

31. Mosca L, Grady D, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Effect of raloxifene on stroke and venous thromboembolism according to subgroups in postmenopausal women at increased risk of coronary heart disease. Stroke 2009; 40: 147-155.

32. Wells G, Tugwell P, Shea B, et al.v Meta-Analysis of the efficacy of hormone replacement therapy in treating and preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Endocrine Rev 2002; 23: 529-539.

33. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321-333.

34. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet 2019; 394: 1159-1168.

35. Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA 2007; 297: 1465-1477.

36. Davis SR, Taylor S, Hemachandra C, et al. The 2023 Practitioner’s Toolkit for Managing Menopause. Climacteric 2023; 26: 517-536.

37. Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1434-1441.

38. Gilsenan A, Midkiff K, Harris D, Kellier-Steele N, McSorley D, Andrews EB. Teriparatide did not increase adult osteosarcoma incidence in a 15-year us postmarketing surveillance study. J Bone Miner Res 2021; 36: 244-251.

39. Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1532-1543.

40. Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, et al. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1417-1427.

41. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Therapeutic Goods Administration. New warnings of romosozumab (Evenity) cardiovascular risks 2023. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/news/safety-updates/new-warnings-romosozumab-evenity-cardiovascular-risks (accessed August 2024).

42. Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al. Bisphosphonate-Associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: Report of a Task Force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22: 1479-1491.

43. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Aghaloo T, Carlson ER, Ward BB, Kademani D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons' Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2022 Update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2022; 80: 920-943.

44. Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25: 2267-2294.

45. Black DM, Geiger EJ, Eastell R, et al. Atypical femur fracture risk versus fragility fracture prevention with bisphosphonates. N N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 743-753.

46. Lenchik L, Kiebzak GM, Blunt BA. What Is the role of serial bone mineral density measurements in patient management? J Clin Densitom. 2002; (5 Suppl): s29-s38.

47. The International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2019 ISCD official positions - adult 2019. Available online at: https://iscd.org/learn/official-positions/adult-positions/ (accessed August 2024).