A 53-year-old woman with postmenopausal symptoms

This case study describes a 53-year-old woman who presents with hot flushes, night sweats, tiredness and reduced libido, which are affecting her self-esteem. Her options for menopausal hormone therapy are discussed, as well as the side effects, benefits and risks of therapy.

- Lifestyle recommendations are first-line management strategies for women experiencing postmenopausal symptoms,

- Within the first one to two years after the final menstrual period, sequential/cyclical menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is recommended.

- After one to two years of the final menstrual period, most women prefer continuous oestrogen–progestogen therapy to avoid further bleeding and give greater endometrial protection.

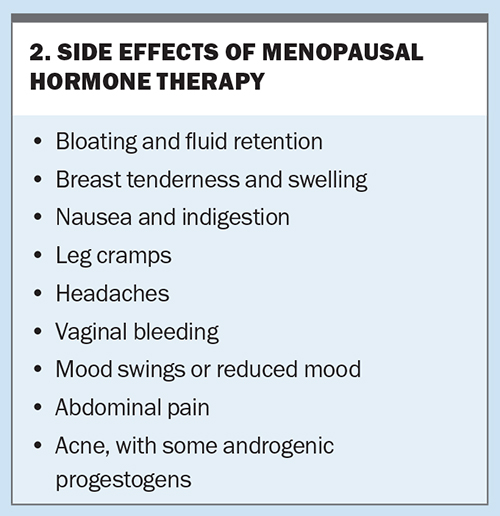

- Side effects from MHT are common but usually settle within the first few months of therapy.

- Informing a woman of the risks and benefits of MHT enables her to decide what MHT she wishes to trial.

Menopause refers to the final menstrual period; therefore, the diagnosis is always retrospectively made after 12 months of amenorrhoea. Once a woman is 12 months past her final menstrual period, she is postmenopausal for the rest of her life. Commonly reported symptoms include:

- vasomotor symptoms of hot flushes and sweats usually at night, with sleep disturbance

- muscle and joint aches and pains

- anxiety and irritability

- decreased concentration

- loss of libido

- vaginal dryness and other genitourinary symptoms related to lack of oestrogen, including painful intercourse (dyspareunia)

- fatigue and tiredness

- crawling sensations on the skin (formication)

- reduced wellbeing and diminished quality of life.

After the menopause, women are at increased risk of developing heart disease, osteoporosis, central adiposity, genitourinary disorders and mood disorders.

Case scenario

Ms B is a 53-year-old company director who presents with hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbance, tiredness, difficulty with word finding, reduced libido and some dyspareunia due to vaginal dryness. Her last menstrual period was at age 51 years and, since then, she has had no further spotting, staining or bleeding. Her last cervical screen was 12 months ago and her mammogram is due at the end of 2023. Her last blood test revealed her fasting cholesterol level was 6.3 mmol/L but her cholesterol/HDL ratio was normal.

Her exercise routine has suffered and her alcohol consumption increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and she has gained weight. She stopped smoking five years ago because of regular bronchitis. Her body mass index is 29 kg/m2 and her blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg. A history and examination reveal no other abnormalities. She lives alone and has no children, but has a partner who lives nearby. Her mother has osteoporosis and her father has had prostate cancer and hypertension, all controlled.

Her symptoms are embarrassing her, especially when she is presenting in important meetings, and her self-esteem, confidence and body image are diminished. She has tried a number of over-the-counter menopause products but none have been effective in relieving her symptoms. She wants to try menopausal hormone therapy (MHT, previously known as hormone replacement therapy [HRT]).

Investigations

Ms B should undergo general blood tests, including measurement of total cholesterol, glucose, calcium and vitamin D levels, as well as thyroid function tests and iron studies, if these have not been performed within the past 12 months. Cervical and breast screening tests should also be checked to ensure these are up to date.

Assessment

Menopausal hormone therapy

In a postmenopausal woman who has not had either a premature or early menopause, the lowest effective dose of MHT is prescribed. The usual advice is to start at a low dose and increase at a later consultation if there has been inadequate symptom relief.

Within the first one to two years after the final menstrual period, sequential/cyclical MHT is recommended, comprising continuous oestrogen plus progestogen for 12 to 14 days per cycle to ensure a regular bleed occurs. After that time, most women prefer continuous oestrogen–progestogen therapy to avoid further bleeding and give greater endometrial protection. If a woman has had a hysterectomy, then she requires oestrogen-only therapy, as the role of progestogen is primarily to protect the endometrium from the normal proliferation of oestrogen.

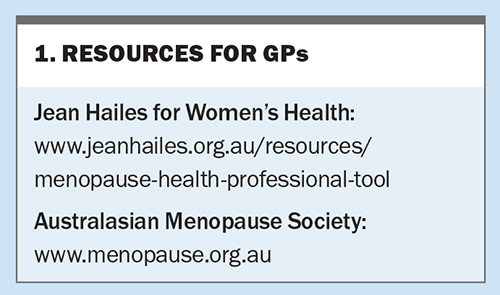

MHTs include various oestrogen–progestogen preparations, both oral and transdermal, the steroid tibolone, tissue-selective estrogen complex comprising a conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene combination, and individual oestrogen-only and progestogen-only products. An up-to-date list is available (www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/ams-guide-to-equivalent-mht-hrt-doses). Other resources on menopause are listed in Box 1.

Side effects from MHT are common (Box 2) but usually settle within the first few months of therapy. Breakthrough bleeding within the first six months of therapy is not considered abnormal unless it is prolonged. Any breakthrough bleeding after that time should be investigated for a cause such as an endometrial polyp.

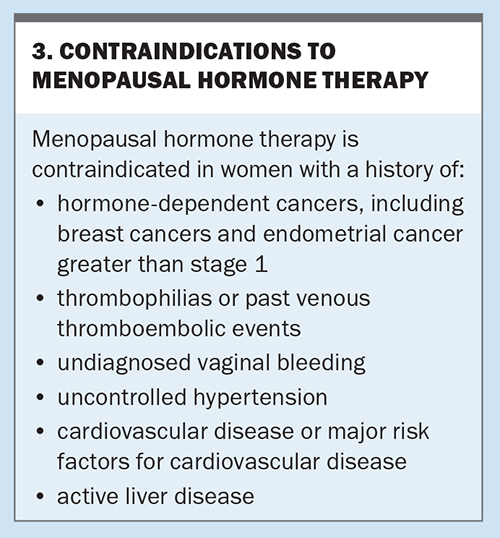

Nonhormonal prescription therapies or referral to a menopause specialist or clinic should be recommended to women in whom MHT is contraindicated. Contraindications for MHT are listed in Box 3. Nonhormonal prescription therapies include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, gabapentin or pregabalin (both used for chronic pain or as antiepileptic medications) and clonidine (an antihypertensive that has been used for many years). Oxybutynin (used for an overactive bladder) has also been used for vasomotor symptoms.1 These agents have shown a reduction of vasomotor symptoms in research studies and all are used off-label for this purpose. Other therapies that have shown some reduction in vasomotor symptoms include cognitive behavioural therapy and hypnotherapy.

Risks of MHT

MHT increases the risk of breast cancer, although the level of risk depends on the therapy prescribed, the dose and duration of therapy and the age of the woman. Oestrogen-only therapy is associated with a lower risk than combined therapy. The risks are lower in women aged 50 to 59 years, and increase with ongoing use. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study showed that the risk of breast cancer increased by eight additional breast cancer cases per 10,000 for women on oestrogen–progestin therapy for five years or more.2 Results from two nested case-control studies showed an additional three cases per 10,000 women years for oestrogen-only therapy and nine additional cases per 10,000 women years for oestrogen–progestogen therapy in women near the menopause and up to five years’ use. The risk decreased after stopping MHT.3 However, a long-term follow up of women in the WHI study showed a reduced incidence of breast cancer in the oestrogen-only group.4 Progestogens, progesterone and dydrogestrone have a lower risk of breast cancer compared with medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethisterone and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, which are associated with a higher risk.3

The risk of breast cancer in women with a positive family history is the same whether they are on MHT or a nonuser. The risk is increased in women with obesity but is not compounded if on MHT. Importantly, there is no increased breast cancer risk for women using vaginal oestrogen-only therapy.

In women taking oral MHT, the risk of thromboembolism increased by two to three per 1000 women years compared with one per 1000 woman years in those not taking MHT. There was no increase in thromboembolic risk with transdermal MHT use; however, the data only included up to medium doses. Women with obesity and those who smoke have higher rates of venous thromboembolism, which is increased further if they take oral MHT.5

Cardiovascular disease risk is not increased in women using MHT within 10 years of the menopause. It is associated with age at which MHT is commenced and increasing age. Overall, protection from heart disease and reduced mortality was seen in women prescribed MHT at 50 to 60 years of age or within 10 years of their final menstrual period.6

Management

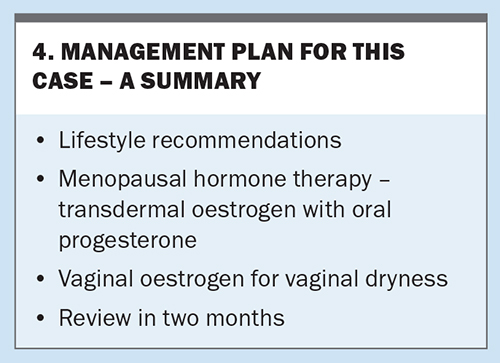

Lifestyle recommendations are first-line management strategies. For Ms B, these include:

- assessment of diet with recommendations for healthy eating

- referral to a dietitian to assess her diet if she wants to lose weight

- recommendation of an exercise program to suit her lifestyle and encouragement of daily exercise

- recommendation to reduce her alcohol consumption, which may also lead to weight loss

- check of her emotional health as she has a high-level position that requires good memory and concentration, is working from home and lives alone and was isolated during COVID-19 lockdowns.

As it has been two years since Ms B’s final menstrual period, a continuous regimen of oestrogen–progestogen therapy is suitable. The risks of thrombosis are lower with a transdermal oestrogen product and progesterone use.

Vaginal oestrogen, either a tablet, pessary or cream, is suitable to help Ms B’s vaginal dryness. Inserting the oestrogen into the lower-third of the vagina is recommended because of the pudendal and perineal vessels supplying the lower pelvis, with lower levels of oestrogen absorption in the lower-third compared with the upper two-thirds.7 A summary of Ms B’s management plan is presented in Box 4.

Conclusion

Menopause treatment options vary with the phase at which a woman presents – in the perimenopause, the immediate postmenopause or some years later. Her symptom complex, past and family history and her own preferences will guide her treatment. Informing the woman of the risks and benefits enables her to decide what MHT she wishes to trial. If MHT is contraindicated, nonhormonal therapies are effective and should be offered. Above all, it is important to tailor the therapy to meet each individual woman’s needs. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Farrell has received consultation fees from Vifor Pharma and Theramex; presented lectures for Vifor Pharma, Besins Healthcare and Theramex; is a Gynaecology Consultant to Medical Panels Victoria; and is Medical Director and Board Member for Jean Hailes for Women’s Health.

References

1. Leon-Ferre R, Novotny P, Wolfe E, et al. Oxybutynin vs placebo for hot flashes in women with or without breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial (ACCRU SC-1603). JNCI Cancer Spectr 2020; 4: pkz088.

2. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321-333.

3. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case control studies using the QResearch and CRPD databases. BMJ 2020; 371: m3873.

4. Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Aragaki AK, et al. Association of menopausal hormone therapy with breast cancer incidence and mortality during long-term follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2020; 324: 369-380.

5. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using QResearch and CRPD databases. BMJ 2019; 364: k4810.

6. Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (3): CD002229.

7. Eden J. Vaginal atrophy and sexual function. Health Ed Expert 2017; 15.