Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: reducing the risk of fracture

Use of oral glucocorticoids is associated with substantial increases in fracture risk, particularly at the spine. Management involves estimating an individual’s fracture risk and, if high, offering bone protective therapies.

- Doses of 7.5 mg/day or greater of prednisone or prednisolone over a three-month period increase the risk of spine facture about fivefold and hip fracture twofold.

- Postmenopausal women who take glucocorticoids can be at high fracture risk regardless of their bone mineral density.

- If the patient has lost contact with their specialist, a priority is to determine if glucocorticoids are still required or if the dose can be reduced.

- In people taking long-term glucocorticoids therapy, general measures to support bone health include ensuring vitamin D levels are adequate and considering oral calcium supplementation.

- The recently produced Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ guideline for the management of osteoporosis contain a fracture risk-based approach that can also be used in patients taking glucocorticoids.

- In terms of treatment choice, most guidelines recommend a bisphosphonate (oral or intravenous) as the initial treatment for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, with denosumab as an alternative.

Despite the introduction of highly specific biological anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids are still widely used in many situations. Although clinicians exercise great caution in prescribing glucocorticoids, epidemiological studies suggest that their use is not diminishing. Oral glucocorticoids are used chronically in 3 to 4% of the population, with maximum use in people aged 60 to 70 years.1 Although general practitioners are the main prescribers, it is likely that the first treatment is initiated in a hospital setting or through a specialist. This can create tension regarding which clinician has ultimate responsibility for monitoring and managing any glucocorticoid side effects.

Risks associated with glucocorticoid use – bone and beyond

Although glucocorticoids are highly effective for many inflammatory conditions, they have a wide range of adverse effects. Many of these adverse effects are well known textbook features, such as central obesity, moon facies, osteoporosis and an increased risk of diabetes. There are, however, other less recognised consequences, such as severe sepsis and pulmonary embolism.2 Although many of these risks are dose and duration dependent, the risk of fracture, severe infection and pulmonary embolism are increased even with short courses of glucocorticoids. Although effective therapies are available to protect bones against the effects of glucocorticoids, attempts to reduce or cease glucocorticoid treatment should always be the first thought.

Glucocorticoids have complex and incompletely understood effects on bone health. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis might be considered a separate metabolic bone disease because it is different in its pathophysiology from other causes of bone loss, such as postmenopausal osteoporosis or treatment with aromatase inhibitors. The risk of fracture during glucocorticoid treatment increases substantially within weeks of treatment. Likewise, the increased risk decreases very quickly when glucocorticoids are ceased, with fracture risk decreasing back to baseline within six to 12 months.3 These changes in risk occur well before changes in bone mineral density (BMD) are observed.

Glucocorticoid use increases fracture risk in a dose- and duration-dependent manner. Doses of 7.5 mg/day or greater of prednisone or prednisolone increase the risk of spine facture fivefold and hip fracture twofold.3 Although glucocorticoid use can reduce BMD, what is more important is that they increase the risk of fracture. This increase in risk is much more than implied by BMD changes alone. When considering the risks to bone from glucocorticoid treatment, a clinician will typically have to consider a patient’s baseline risk of fracture and how this will be influenced by the increased risk caused by glucocorticoids. As such, groups with baseline low fracture risk (e.g. premenopausal women and younger men) are often still at a relatively low absolute risk of fracture even during exposure to high doses of glucocorticoids. By contrast, postmenopausal women, even in the absence of osteoporosis using BMD criteria, will have clinically significant increases in fracture risk with use of glucocorticoids that will often warrant bone protective treatment. Clinical trials have highlighted that fractures are rare during glucocorticoid treatment in premenopausal women and younger men with a BMD T-score of greater than –1.5.4 Conversely, many people with a T-score between –1.5 and –2.5 are at a higher risk of fracture than might be expected. This threshold of –1.5 has been incorporated into many treatment algorithms and criteria for reimbursement, such as in the PBS. A low-trauma fracture occurring while taking glucocorticoid treatment is also considered to be a very strong risk factor for further fractures. The development of a spine fracture while taking glucocorticoids is particularly concerning. A vertebral fracture alters the way forces are transmitted through the rest of the spine and this can lead to a ‘domino’ effect whereby one fracture leads to multiple fractures with consequent deformity and long-term health consequences. On a positive note, although randomised controlled trials examining the effectiveness of treatments for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis were relatively small, they did show a significant reduction in risk of spine fractures.4

Identifying and treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

Various approaches can be taken to minimise the risk of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and glucocorticoid-associated fractures. The ideal approach is to find ways of reducing the dose of glucocorticoids. In many situations, glucocorticoids have been initiated by a specialist and it would be inappropriate for a primary care physician to stop these without advice. However, if the patient has lost contact with their specialist, a priority would be to re-establish contact and ask the question whether the glucocorticoids are still required or if the dose can be reduced. If the glucocorticoid dose can be reduced or stopped, one barrier to stopping them is the fear of adrenal suppression and an Addisonian crisis. A practical guide to safely reducing and stopping long-term glucocorticoids has recently been published.5

Investigations

Initial tests for determining fracture risk include measurement of serum vitamin D levels and renal function. Measuring BMD using dual-energy absorptiometry (DXA) is usually helpful to determine an individual’s initial fracture risk and can be used as a baseline for longer term bone-health management. This test should be carried out early if glucocorticoids are likely to be used for longer than three to four months, as bone protective therapies can be started in anticipation of long-term glucocorticoid therapy.

General measures to support bone health

In people taking long-term glucocorticoid therapy general measures to support bone health include ensuring vitamin D levels are adequate (25-hydroxy vitamin D levels 50 nmol/L or higher) and, unless contraindicated, considering oral calcium supplementation. The blanket use of calcium supplementation in people with postmenopausal osteoporosis has been questioned recently on the basis of relative lack of effectiveness, poor tolerability and possible long-term adverse effects. However, glucocorticoid treatment can reduce calcium absorption and encourage urinary calcium loss, making calcium use in the setting of glucocorticoid use appropriate. Trials examining treatments for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis typically used calcium supplementation (1000 mg/day) in both the active treatment and placebo arms.

Resistance exercise is now recognised as an important approach to improving bone health. However, evidence for exercise in the context of glucocorticoid treatment is lacking.

Pharmacotherapy for bone protection

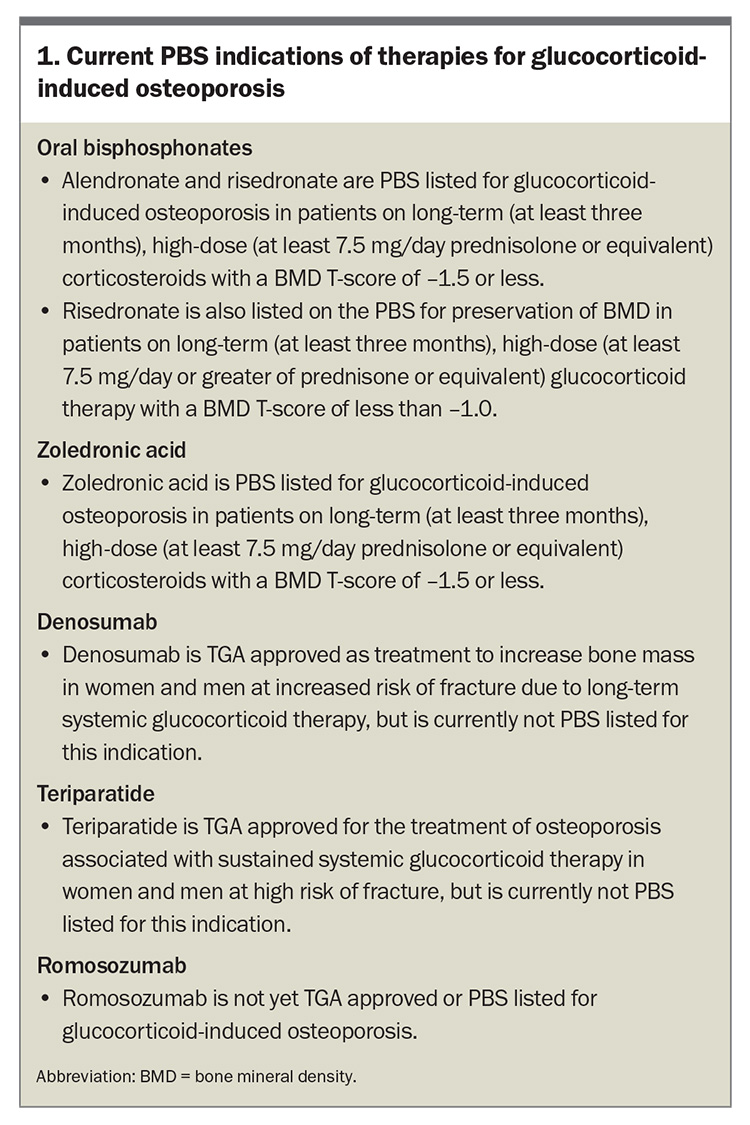

If pharmacotherapy is required for bone protection there are various options available. Current therapies for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and their PBS indications are summarised in Box 1.

Oral bisphosphonates

The medications with the greatest evidence base for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis are the oral bisphosphonates. Alendronate and risedronate are both highly effective in reducing the risk of fracture in people treated with glucocorticoids.4 Daily, weekly or monthly treatment are all options, but most patients prefer weekly or monthly treatment. Some of the underlying conditions that require glucocorticoid treatment can complicate the use of oral bisphosphonates. These conditions include inflammatory disease affecting the upper gastrointestinal tract and conditions associated with chronic kidney diseases. Oral bisphosphates are contraindicated in patients who have chronic kidney disease with an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 30 to 35 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Zoledronic acid

In patients at risk of upper gastrointestinal complications associated with the use of oral bisphosphonates or those who develop gastrointestinal symptoms with use of these medications, intravenous zoledronic acid is an excellent, evidence-based option.6 Intravenous zoledronic acid is given in a hospital or an infusion centre, which might be a barrier to its use or might delay its initiation. Treatment is typically once per year and for some diseases that require use of glucocorticoids, such as polymyalgia rheumatica, a single dose of zoledronic acid might be all that is required. A list of infusion sites administering zoledronic acid is provided on the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society website (www.anzbms.org.au/infusion-centres-for-zoledronic-acid.asp).

Denosumab

Denosumab treatment has also been examined in clinical trials of patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and it appears to be at least as effective as bisphosphonates.7 Its safety and convenience make this drug appealing, particularly in people who might have issues with bisphosphonate therapy. It can be used in patients with poor renal function, although there is an increased risk of developing hypocalcaemia in this setting. Specialist advice is important in this situation because people with chronic kidney disease can have a variety of bone conditions that might complicate management.

One of the main issues with denosumab is that any bone gained while using the drug is rapidly lost when the drug is stopped. This means that for many patients the drug has to be used lifelong unless an ‘exit strategy’ is employed, such as short-term treatment with a bisphosphonate. In the context of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, there is less concern about this, particularly when the duration of use is expected to be relatively short (e.g. one to two years). However, short-term treatment with a bisphosphonate (if not contraindicated) is still recommended in most people who are treated with denosumab. Denosumab is not listed on the PBS for the indication of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Many patients who are good candidates for this medication would be required to pay the full cost.

Teriparatide

Perhaps the most potent medication for the treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis is teriparatide, which is given as a daily injection for a duration of 18 to 24 months. This medication has shown superiority to oral bisphosphonates in reducing the risk of spine fracture.8 Teriparatide does not have a PBS indication for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. It is, however, PBS listed for severe established osteoporosis in which patients must have had two or more fractures with one of these symptomatic and occurring despite taking an antiresorptive agent for at least 12 months. The BMD T-score also needs to be –3 or below on a DXA scan. In general, referral to a specialist is appropriate in patients who experience fractures during treatment with a bisphosphonate or denosumab, and teriparatide therapy is likely to be a consideration in this situation.

Romosozumab

Another anabolic (bone building) drug, romosozumab, has recently been introduced in Australia. This is administered as a monthly injection and is TGA approved for women with postmenopausal osteoporosis at high risk of fracture and men with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture. Although this drug might become useful for treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, it is much less studied in this situation than the other medications described above. Discussion with a specialist is required if this drug is being considered.

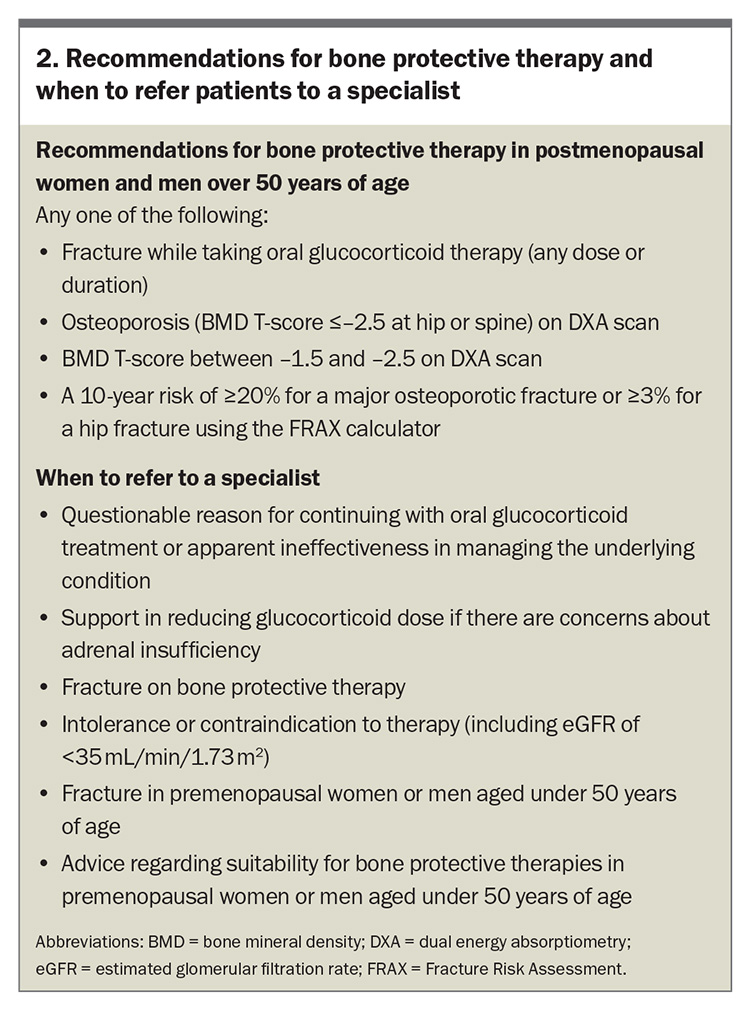

Management guidelines for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

There is no nationally agreed management approach for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Some international organisations, most notably in the USA and UK, have developed guidelines. These are typically based on estimates of absolute risk, incorporating the patient’s age and the presence of previous fractures using the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) Tool. The recently produced guideline from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners does not directly address the issue of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.9 However, this Australian guideline emphasises the use of the FRAX calculator, which gives a 10-year estimate of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) and hip fracture. Treatment with prednisone (or equivalent) at a dose of 7.5 mg/day or greater for more than four months is an indication for assessment and the FRAX algorithm incorporates a question about glucocorticoid use. Following this guideline, a patient with a BMD T-score of –2.5 or less, or a patient with a T-score of between –1.5 and –2.5 and a FRAX score of 20% or more for a MOF, or 3% or more for hip fracture, would be a candidate for treatment. The development of a fracture while taking glucocorticoids is also a strong indication for treatment regardless of BMD or FRAX score.

A limitation of the FRAX calculator is that the dose of glucocorticoid is typically set at about 5 mg/day. In patients taking doses greater that 7.5 mg/day, it is suggested that the risks of MOF and hip fracture be increased by 15% and 20%, respectively. These adjustments can be made using the FRAXplus calculator but there are additional costs to using this calculator.

A further limitation of the FRAX tool is that the BMD used is that of the femoral neck, whereas patients treated with glucocorticoids have their highest risk of fracture at the spine. As such, we recommend that postmenopausal women and men aged over 50 years who are taking prednisone (or equivalent) at a dose of 7.5 mg/day with a BMD T-score of between –1.5 and –2.5 at the spine also be offered bone-protective treatment, even if their fracture risks based on the hip are modest. These people are typically covered by the PBS for reimbursement.

In terms of treatment choice, most guidelines recommend a bisphosphonate (oral or intravenous) as the initial treatment, with denosumab as an alternative, particularly in the special situations described above where bisphosphonates might be contraindicated. Treatment should be continued for about six to 12 months after stopping glucocorticoids and then a reassessment of fracture risk using bone densitometry and the FRAX calculator is needed to determine if longer term treatment is suitable for postmenopausal osteoporosis. General recommendations for bone protective treatment and when to consider referral to a specialist are outlined in Box 2.

The evaluation and management of bone health in younger people treated with long-term glucocorticoid therapy (e.g. men younger than 50 years and premenopausal women) is complicated with risks of under- and overtreatment. Referral of patients to a specialist is generally recommended in this setting.

Inhaled or topical glucocorticoid treatment

Glucocorticoids given by other routes can also increase fracture risk and lower BMD. These risks are, however, generally much lower than with oral glucocorticoids. The most common clinical situation is inhaled glucocorticoid use for asthma. Standard doses of inhaled glucocorticoids do not appear to increase fracture risks. However, daily doses equivalent to 1000 mcg fluticasone or more can adversely impact bone.10 As a practice point, patients who have clinically significant effects of inhaled or topical glucocorticoids on bone would likely have suppressed adrenal function. A low morning cortisol level (e.g. less than 200 nmol/L) or a poor response to a 250 mcg Synacthen test (peak level <450 nmol/L) indicates systemic glucocorticoid exposure and the patient should be treated as if they are taking oral glucocorticoids. In clinical practice, this type of testing might be reserved for a patient on higher doses of inhaled glucocorticoids who has experienced a fracture or develops other clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome, such as easy bruising.

Conclusion

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis continues to be a clinically significant problem. It should always be borne in mind that drugs to protect the bones will not address the other harms associated with glucocorticoid use. However, there are several drugs that can substantially reduce fracture risk and use of simple algorithms can guide their use. One of the most important management issues is ensuring that the responsibility for assessing patients for this risk is clarified between the primary care physician and the specialist. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Bjornsdottir HH, Einarsson OB, Grondal G, Gudbjornsson B. Nationwide prevalence of glucocorticoid prescriptions over 17 years and osteoporosis prevention among long-term users. SAGE Open Med 2024; 12: 20503121241235056.

2. Waljee AK, Rogers MAM, Lin P, et al. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: population based cohort study. BMJ 2017; 357: j1415.

3. van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L, Zhang B, Cooper C. Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2000; 15: 993-1000.

4. Sambrook PN. Corticosteroid osteoporosis: practical implications of recent trials. J Bone Miner Res 2000; 15: 1645-1649.

5. Torpy DJ, Lim WT. Glucocorticoid-induced adrenal suppression: physiological basis and strategies for glucocorticoid weaning. Med J Aust 2024; 220: 539.

6. Reid DM, Devogelaer JP, Saag K, et al. Zoledronic acid and risedronate in the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (HORIZON): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 1253-1263.

7. Saag KG, Wagman RB, Geusens P, et al. Denosumab versus risedronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, double-dummy, non-inferiority study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 445-454.

8. Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S, et al. Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2028-2039.

9. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and Healthy Bones Australia. Osteoporosis management and fracture prevention in post-menopausal women and men > 50 years of age. Melbourne: RACGP; 2024. Available online at: https://healthybonesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/hba-racgp-guidelines-2024.pdf (accessed November 2024).

10. van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Use of inhaled corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2001; 16: 581-588.