Endocrine causes of osteoporosis. Part 2: Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

Endocrine causes of osteoporosis, such as primary hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism, glucocorticoid excess, acromegaly, Cushing’s syndrome and hyperthyroidism, are well-recognised risk factors for decreased bone mineral density. Optimal management of bone health in people with these conditions involves treating the underlying hormonal disease and assessing the need for specific bone preservation therapy. This three-part series discusses the management of three different cases to highlight the detrimental impact of specific endocrine disease on bone health.

- Glucocorticoid-related bone loss can occur within three months of starting glucocorticoids.

- Maintaining the lowest dose of glucocorticoids reduces the long-term adverse effects on bone.

- Bisphosphonate therapy can be considered and is PBS-subsidised for patients receiving high-dose glucocorticoids (equivalent to prednisolone 7.5 mg daily) long term (for three months or more) who have a BMD T-score of –1.5 or less, even in the absence of minimal trauma fracture.

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

Case scenario

Mr Singh, a 65-year-old man who recently moved to Australia, was admitted under the general medical unit for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia following exclusion of COVID-19 infection. It was noted that he was taking prednisolone for more than four years for an undefined lung condition.

The prednisolone dose had changed over time, with doses up to 30 mg daily used during exacerbations of his airways disease and weaned down to 7 mg daily when stable. The endocrine unit was consulted to advise an appropriate steroid weaning protocol.

On examination, Mr Singh had Cushingoid features of facial plethora, a posterior fat pad, central adiposity and marked proximal muscle weakness that impaired his ability to climb up stairs. There was no obvious midline vertebral tenderness, but a thoracolumbar x-ray was requested to exclude fractures. A dual x-ray absorptiometry scan was also performed and Mr Singh was followed up in the endocrine outpatient clinic.

The thoracolumbar x-ray revealed a crush fracture at L4 with anterior wedging of more than 20%, consistent with a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Dual x-ray absorptiometry was performed to facilitate monitoring of bone mineral density (BMD) following treatment. This demonstrated low BMD with a T-score of –2.4 at the lumbar spine and –2.0 at the femoral neck. Screening for other secondary causes of osteoporosis was unremarkable. It was determined that the predominant cause of osteoporosis was long-term glucocorticoid use. He was treated with intravenous zoledronic acid 5 mg. Due to his severe reflux symptoms oral bisphosphonates were unsuitable. A respiratory consultation was requested to further investigate the underlying cause of the patient’s lung pathology. Mr Singh received ongoing review through the endocrine outpatient clinic to assist with his corticosteroid weaning and osteoporosis treatment.

Discussion

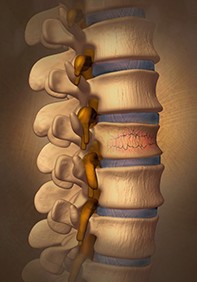

More than 10% of people who are taking glucocorticoids develop fractures and it is the most common cause of secondary osteoporosis.1 Glucocorticoids induce rapid bone loss, particularly at sites rich in trabecular bone. These changes are mediated by stimulation of the nuclear glucocorticoid receptor and subsequent osteoclast activation and osteoblast downregulation.2 They also influence calcium handling in the kidneys and the gastrointestinal tract and reduce sex hormone production (Figure).3

At the lumbar spine, a daily dose of prednisolone (or its equivalent) of more than 7.5 mg can lead to a reduction in BMD of up to 8% after 20 weeks, with the most severe bone loss occurring in the first 12 months.4 The risk of fracture is increased after three months of starting glucocorticoids and is dose-dependent, with a meta-analysis demonstrating increased risk of fracture even with low-dose glucocorticoids.4 The risk of vertebral fractures can increase fivefold and the risk of hip fractures can double.5 Patients taking glucocorticoids can also sustain fractures at a higher BMD compared with women who have postmenopausal osteoporosis.5

Glucocorticoids are widely used in a range of rheumatological, respiratory, neoplastic and inflammatory bowel disorders due to their anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. Some of these disorders manifest early in life, resulting in early and prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids and contributing to failure to achieve peak bone mass, bone loss and increased fracture risk in young adults. Although prescribing the lowest required dose of glucocorticoids and downtitration of dose will minimise bone loss, other measures are also recommended for people taking glucocorticoid therapy. In addition to maintaining a regular routine of weight-bearing exercise, adequate dietary calcium intake will also assist in maintaining bone health. A daily intake equivalent to 1200 mg of elemental calcium and 1000 IU of vitamin D is recommended.6

The PBS subsidises bisphosphonate therapy for patients receiving high-dose glucocorticoids (equivalent to prednisolone 7.5 mg daily) long term (for three months or more) who have a BMD T-score of –1.5 or less, even in the absence of minimal trauma fracture. For those who have sustained a minimal trauma fracture and thereby have established osteoporosis, antiresorptive medications can be prescribed regardless of BMD. Denosumab has demonstrated efficacy in treating glucocorticoid-induced bone disease, but is not currently subsidised on the PBS for this indication.8 Teriparatide has also been proven to be effective for patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis but it is not PBS listed for this indication (see Box).9

The risk of fracture declines almost back to baseline after 12 months of glucocorticoid cessation.10 It is also important to address the other systemic complications of steroid toxicity, such as diabetes, cataracts and muscle wasting. These can lead to peripheral neuropathy, visual impairment and proximal weakness resulting in an increased risk of falls and subsequent fractures. In patients with planned or ongoing chronic exposure to glucocorticoids, it is prudent to refer them to an endocrinologist for an individualised clinical assessment of risk and targeted management of their osteoporosis and fracture risk. ET