Treating vasomotor symptoms during menopause

Vasomotor symptoms significantly impact the quality of women’s lives. Menopausal hormonal therapy remains the first-line treatment of vasomotor symptoms and can be used for the duration of bothersome symptoms rather than arbitrarily ceased. Transdermal oestrogen and body identical hormones may represent lower risk options. If menopausal hormonal therapy is not appropriate, fezolinetant is an emerging effective treatment option.

- Vasomotor symptoms are the most common symptom of the menopause transition and usually start several years before the final menstrual period.

- Although the median duration of vasomotor symptoms is about 7.4 years, there are women who will experience persistent symptoms.

- Menopausal hormone therapy can be started before the final menstrual period if bothersome symptoms are present and initiated up to 10 years from the final menstrual period.

- The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms is menopausal hormone therapy and the use of transdermal oestrogen and body identical hormones may be preferred because of a better safety profile.

- If initiated, menopausal hormone therapy can be used for the duration of bothersome symptoms, rather than ceased arbitrarily at five years.

- A new nonhormonal medication, fezolinetant, is now available and is an effective option for women who do not wish to take hormone therapy or for whom hormone therapy is not appropriate.

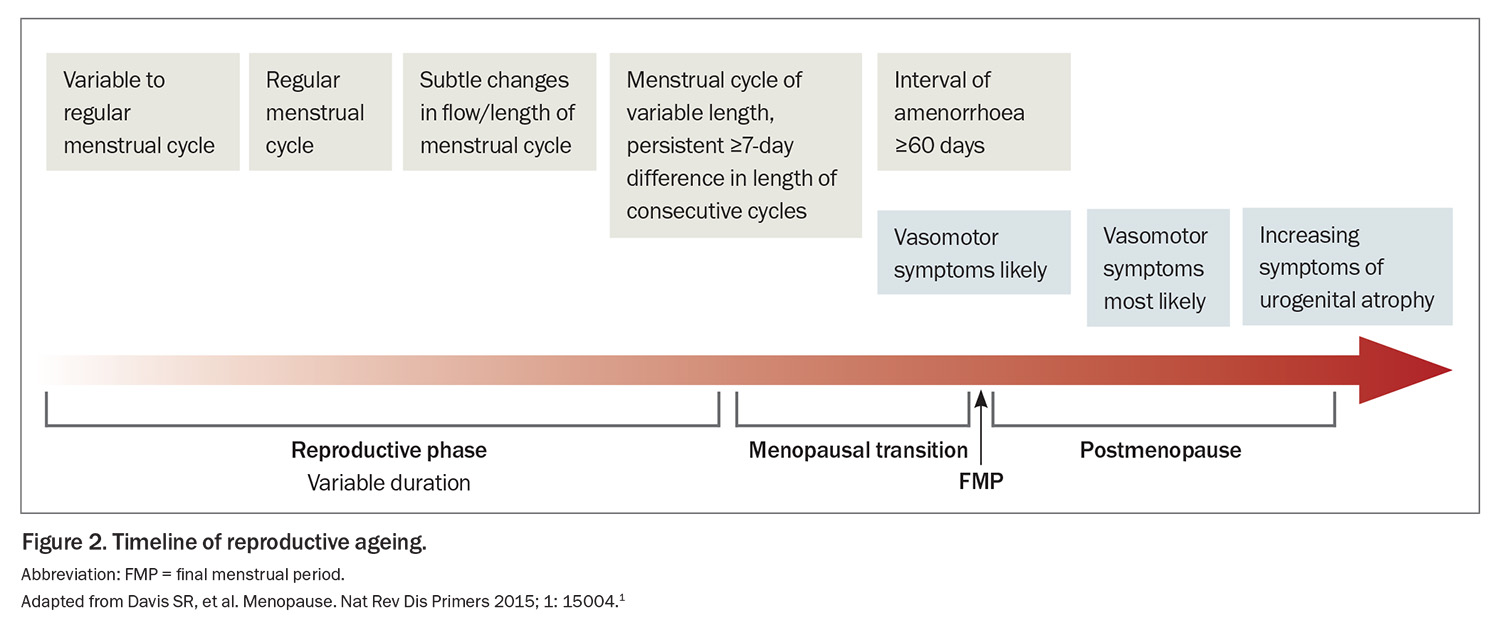

Vasomotor symptoms are the most well-recognised manifestation of menopause. Vasomotor symptoms range from the mild sensation of heat through to hot flushes and diffuse sweating, accompanied by anxiety and palpitations. The onset of vasomotor symptoms usually precedes the final menstrual period by several years.1

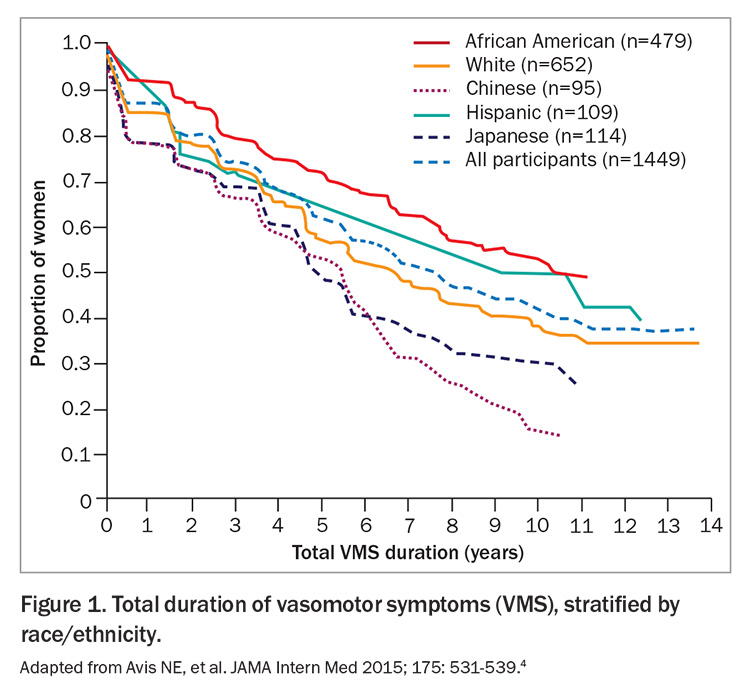

Vasomotor symptoms can have a significant impact on multiple facets of a woman’s life, including sleep disruption, mood changes, poorer concentration and reduced self-esteem.2 Vasomotor symptoms are the most common reason for women to seek help during menopause.3 When managing menopausal symptoms, it is important to be aware of their natural course. The median duration of vasomotor symptoms in a large observational study with a racially diverse population was 7.4 years (Figure 1).4 Importantly, a proportion of women experience persistent hot flushes for many years beyond their final menstrual period.

Menopausal hormone therapy

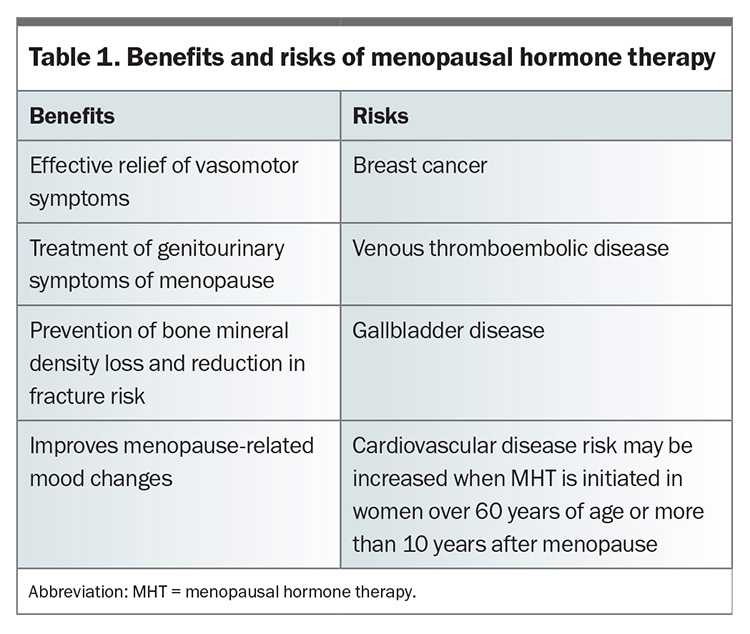

The most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms is menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). It remains the first-line treatment for most women globally.5,6 The benefits of MHT generally outweigh the risks in women under 60 years of age or who are within 10 years of their final menstrual period, although there are several important risks that are discussed below.5 The decision on whether to use MHT should be an exercise in shared decision-making between the clinician and patient, with discussion of both the benefits and risks (Table 1). There are several patient-centred resources on menopause available online from organisations such as the Australasian Menopause Society and Jean Hailes for Women’s Health, which can assist in the shared decision-making process.

Concerns and contraindications of MHT

A key concern among clinicians and women is the risk of breast cancer with use of MHT. The finding of an increased risk of breast cancer with MHT use in the Women’s Health Initiative drastically reduced the use of MHT around the world.7 It is important to discuss this risk with potential candidates for MHT by setting the context that this increased risk is still low, with three additional cases of breast cancer per 1000 women who received five years of conjugated equine estrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate. This is similar in magnitude to the increased risk of breast cancer conferred by obesity yet less risk than the consumption of two glasses of wine each day.8 Importantly, there was no significant difference in breast cancer-related mortality compared with women who did not receive MHT.9

The main contraindication to MHT is prior or current breast cancer and other hormone-sensitive tumours. There are other traditional contraindications including venous thromboembolic disease, coronary artery disease and stroke. However, recent data suggest that transdermal oestrogen, dydrogesterone and micronised progesterone have neutral effects on venous thromboembolic and vascular disease.10,11 In women with these conditions and who do not achieve adequate control of their menopausal symptoms with nonhormonal treatments, MHT with transdermal oestrogen, dydrogesterone and micronised progesterone may be considered. In such circumstances, referral to a specialist service may be prudent.

Timing of initiating MHT: why is this important?

The timing of initiating MHT is important for several reasons. Menopausal symptoms tend to escalate as a woman approaches her final menstrual period and peak around that final bleed (Figure 2). Therefore, this may be an opportune time to initiate treatment, when symptoms are at their worst. Starting MHT within 10 years of menopause is particularly important from a cardiovascular perspective because MHT use in early menopause appears to have a favourable effect on atherosclerosis, and this was demonstrated through surrogate markers such as coronary artery calcification.12 However, several systematic reviews of observational data and randomised controlled trials have not consistently found a clear benefit with cardiovascular outcomes.13 Therefore, MHT is not indicated for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. One of the initial findings of the Women’s Health Initiative was that reintroducing oestrogen and progesterone in older women who were more than 10 years from their final menstrual period increased their absolute risk of cardiovascular disease. However, more recent analysis from extended postintervention follow up of the Women’s Health Initiative suggests that MHT had a neutral effect or slight increase in risk of cardiovascular disease in older women.14 The adverse cardiometabolic changes that occur with the menopause transition as the beneficial effects of oestrogen naturally decline are shown in Table 2.15

Choice of MHT

Choice of MHT regimens will depend on several factors including the presence of a uterus, menstrual bleeding pattern and contraceptive requirements (Figure 3).

The route and type of MHT confer different risks of breast cancer, venous thromboembolic disease and vascular disease. In contrast to oral oestrogen, transdermal oestrogen does not undergo first pass metabolism in the liver and has been shown not to increase the risk of venous thromboembolic disease.16 This is particularly important to consider in patients with other risk factors for venous thromboembolic disease. Observational data from a large cohort study suggest micronised progesterone and dydrogesterone were associated with a much lower risk of invasive breast cancer compared with other progestins.17 There are also some emerging data to suggest that micronised progesterone does not increase cardiovascular disease.11 Tibolone is another MHT option that has been shown not to increase the risk of venous thromboembolic disease and cardiovascular events. Limited data of tibolone use in women with no prior history of breast cancer is also similarly reassuring in that no significant increase in breast cancer was observed.18 However, an increased recurrence of breast cancer was observed with tibolone use in women with previous history of breast cancer.19 An increased risk of stroke was also observed in older women aged over 60 years using tibolone.20

Body identical oestrogen and progestogen are chemically identical to the naturally produced hormones. This results in less side effects and potentially a more favourable safety profile.21 This is distinct from bioidentical hormones, which are compounded preparations that are not subject to external quality control or regulation. The Australasian Menopause Society has an online guide on the preparations of MHT currently available in Australia that are registered with the TGA (see: https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/ams-guide-to-mht-hrt-doses).

MHT that is initiated before the final menstrual period or the current use of some contraceptive methods may make determination of the exact timing of menopause difficult. In such circumstances, biochemical assessment with measurement of follicle-stimulating hormone level (>30 IU/L) in conjunction with age 50 to 55 years is consistent with menopause. The use of the combined contraceptive pill suppresses follicle-stimulating hormone levels, therefore, in such instances, transitioning to an alternative contraceptive method could be considered followed by biochemical evaluation. As most women will be menopausal by the age of 55 years, contraception can be ceased at that age without further assessment.22

When to cease MHT

Treatment with MHT does not necessarily need to be ceased at five years. This common practice arose from the observation that increased breast cancer risk emerges after about five years of combination MHT use.23 However, vasomotor symptoms often last more than five years and, as mentioned above, can be persistent for many more years in some women. The decision to continue MHT beyond five years should take into consideration an individual woman’s symptoms and risks. Studies on when and how to discontinue MHT are lacking. In my clinical practice, I will ask women who have been on MHT for five years to check intermittently on whether they still have ongoing bothersome symptoms by withholding MHT. If symptoms are still persistent, then restarting MHT is reasonable. Often a lower dose can be used at this stage.

Fezolinetant and other nonhormonal therapies

For women who do not wish to use MHT or in whom MHT is not appropriate, there is a new nonhormonal treatment for vasomotor symptoms. Fezolinetant is a neurokinin-3 receptor antagonist and targets the thermoregulatory centre in the hypothalamus. When activated, the thermoregulatory centre reduces body temperature by sweating and peripheral vasodilatation.24 Kisspeptin–neurokinin B–dynorphin (KNDy) neurons innervate this area. Neurokinin binds to neurokinin-3 receptors and stimulates the KNDy neurons whereas oestrogen exerts an inhibitory effect.25

Phase 3 studies of fezolinetant show a significant reduction in both the frequency and severity of hot flushes compared with placebo.26 Fezolinetant reduced hot flushes by about 63% at week 12 and this reduction was maintained for one year, which was the duration of the study.26 Fezolinentant represents an alternative to MHT for treating hot flushes and appears to be more effective than the off-label use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and gabapentin.27 The advantages of fezolinetant include its nonhormonal mechanism and daily oral formulation. However, when considering fezolinetant over MHT, it is important to remember that it does not act beneficially on bone mineral density or treat genitourinary symptoms of menopause. Monitoring of liver function is recommended because of the observation of a mild transaminase rise in some participants in the phase 3 studies. Cessation of fezolinetant leads to resolution of the liver enzyme derangements. The TGA recommend checking liver function at baseline and repeating this within the first three months of initiation. The FDA in the USA have recently recommended more scrutiny with monthly blood tests for the first three months and then every three months for the first year of initiation because of a postmarketing case of liver injury.

Other nonhormonal treatment options are available for hot flushes with varying efficacy. These are centrally acting medications and include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, gabapentin, clonidine and oxybutynin. These nonhormonal options are used off label for vasomotor symptoms. Notably, only paroxetine has an FDA indication in the USA for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. The Royal Women’s Hospital has an informative fact sheet to guide clinicians in the prescribing of nonhormonal treatments (see: https://the womens.r.worldssl.net/images/uploads/fact-sheets/Treating-hot-flushes-280518.pdf).

Summary

Vasomotor symptoms are one of the dominant features of the menopause transition and can significantly impact the quality of women’s lives. These symptoms are present for almost a decade in most women and are still under-reported and undertreated. MHT remains the first-line treatment of vasomotor symptoms, particularly for women aged under 60 years or who are within 10 years of their final menstrual period. Transdermal oestrogen and body identical hormones may represent lower risk options. Duration of MHT use should be tailored to the individual woman rather than arbitrarily ceased. If MHT is not appropriate, fezolinetant is an emerging effective treatment option. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Davis SR, Lambrinoudaki I, Lumsden M, et al. Menopause. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015; 1: 15004.

2. Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, Lewis J, Clark RV. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas 2009; 62: 153-159.

3. Genazzani AR, Schneider HP, Panay N, Nijland EA. The European Menopause Survey 2005: women’s perceptions on the menopause and postmenopausal hormone therapy. Gynecol Endocrinol 2006; 22: 369-375.

4. Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 531-539.

5. de Villiers TJ, Hall JE, Pinkerton JV, et al. Revised Global Consensus Statement on Menopausal Hormone Therapy. Climacteric 2016; 19: 313-315.

6."The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society" Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2022; 29: 767-794.

7. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321-333.

8. Singletary SE. Rating the risk factors for breast cancer. Ann Surg 2003; 237: 474-482.

9. Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Aragaki AK, et al. Association of menopausal hormone therapy with breast cancer incidence and mortality during long-term follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA 2020; 324: 369-380.

10. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases [published correction appears in BMJ 2019; 364: l162]. BMJ 2019; 364: k4810.

11. Kaemmle LM, Stadler A, Janka H, von Wolff M, Stute P. The impact of micronized progesterone on cardiovascular events–a systematic review. Climacteric 2022; 25: 327-336.

12. Manson JE, Allison MA, Rossouw JE, et al. Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2591-2602.

13. Kim JE, Chang JH, Jeong MJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular diseases. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 20631.

14. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310: 1353-1368.

15. Marlatt KL, Pitynski-Miller DR, Gavin KM, et al. Body composition and cardiometabolic health across the menopause transition. Obesity 2022; 30: 14-27.

16. Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: impact of the route of estrogen administration and progestogens: the ESTHER study. Circulation 2007; 115: 840-845.

17. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008; 107: 307-308].

18. Formoso G, Perrone E, Maltoni S, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of tibolone in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 10(10): CD008536.

19. Kenemans P, Bundred NJ, Foidart JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 135-146.

21. Cummings SR, Ettinger B, Delmas PD, et al. The effects of tibolone in older postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 697-708.

21. Gaudard AM, Silva de Souza S, Puga ME, Marjoribanks J, da Silva EM, Torloni MR. Bioidentical hormones for women with vasomotor symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (8): CD010407.

22. Grandi G, Di Vinci P, Sgandurra A, Feliciello L, Monari F, Facchinetti F. Contraception during perimenopause: practical guidance. Int J Womens Health 2022; 14: 913-929.

23. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310: 1353-1368.

24. Depypere H, Lademacher C, Siddiqui E, Fraser GL. Fezolinetant in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021; 30: 681-694.

25. Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, Romanovsky AA, Krajewski-Hall SJ. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neuroendocrinol 2013; 34: 211-227.

26. Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet 2023; 401: 1091-1102.

27. Sahni S, Lobo-Romero A, Smith T. Contemporary non-hormonal therapies for the management of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a literature review. touchREV Endocrinol 2021; 17: 133-137.