Premature ovarian insufficiency: recommendations from the new guidelines

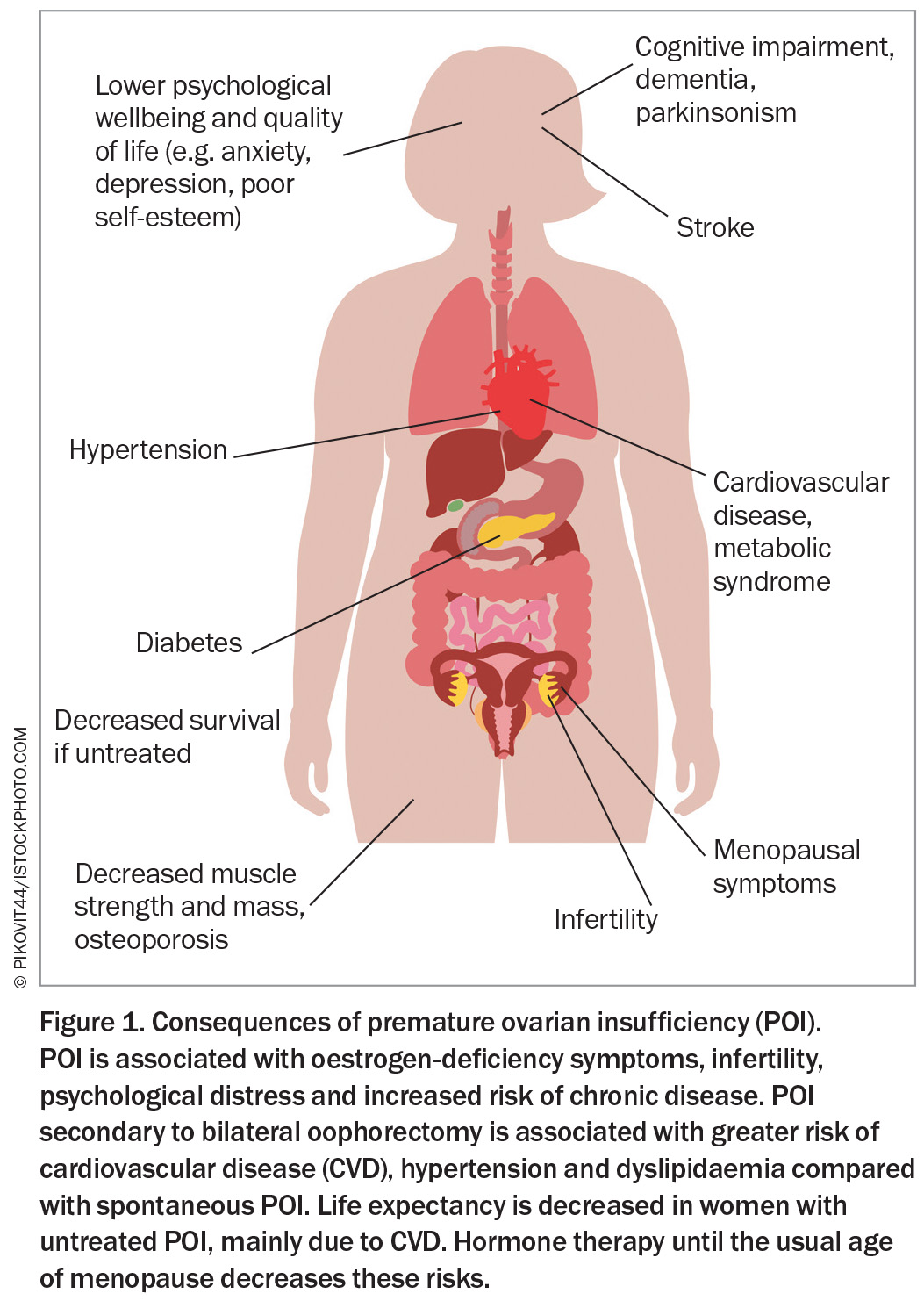

Premature ovarian insufficiency, defined as loss of ovarian function before the age of 40 years, is associated with significant adverse psychological and physical impacts. It presents a diagnostic and management challenge requiring comprehensive evaluation, personalised hormone therapy, psychological support and ongoing follow up for affected women.

- The diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) should be considered in any women aged younger than 40 years presenting with oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea, infertility or oestrogen-deficiency symptoms.

- Diagnostic criteria for POI are oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea for at least four months in a woman aged younger than 40 years plus one elevated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) level of more than 25 IU/L. A repeat FSH level or measurement of anti-Müllerian hormone level is not required unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

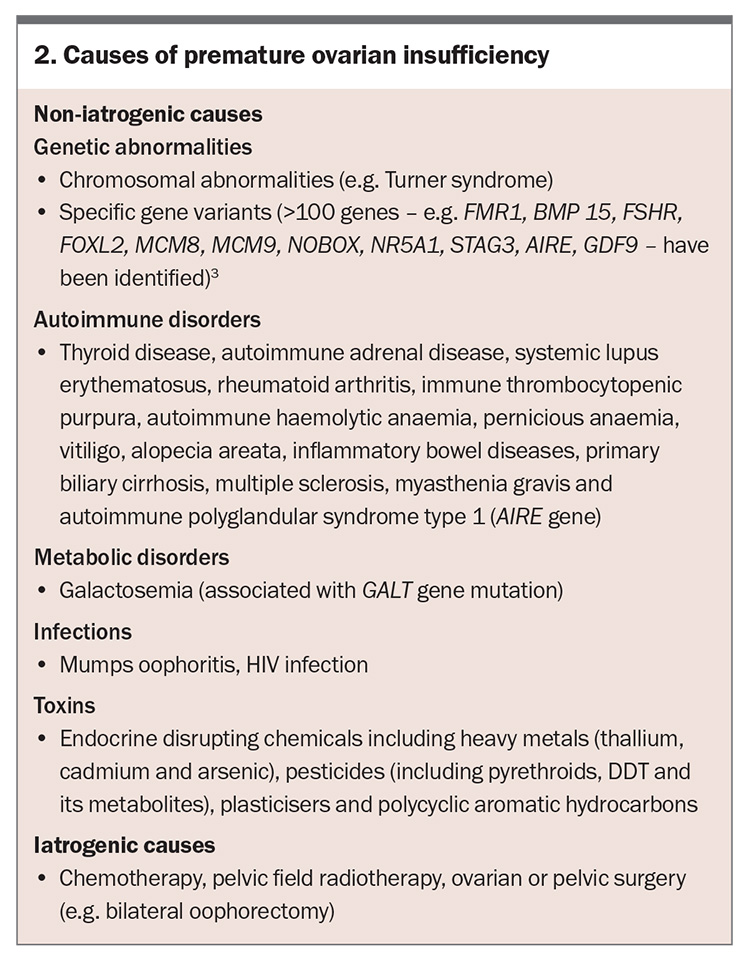

- POI may be secondary to medical treatments or may occur spontaneously. Evaluation for a genetic or autoimmune cause of spontaneous POI is important but most cases are idiopathic.

- POI is associated with an increased risk of multimorbidity, such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease, infertility and decreased survival. Comorbidity screening and appropriate management are needed at diagnosis and throughout life.

- Personalised hormone therapy is the mainstay of treatment and should be initiated promptly and continued until at least the usual age of menopause to minimise risk of long-term sequelae.

- Oocyte or embryo donation is the most reliable method of achieving pregnancy. There are currently no interventions that can reliably restore fertility.

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is defined as the loss of ovarian function before the age of 40 years and is characterised by menstrual disturbance (amenorrhoea or oligomenorrhoea), elevated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) level and low oestrogen level.1 POI is more common than previously thought, with a global overall prevalence of 3.5%.1 It is associated with significant physical and psychological impacts as well as decreased survival if untreated, mainly due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Figure 1).1 Early menopause refers to menopause occurring between the ages of 40 and 45 years, and has a reported prevalence of 12.2%.1 It is also associated with an increased risk of multimorbidity, although the risk ratios are higher the younger the women at menopause. Women with early menopause or POI require hormone therapy until the usual age of menopause as the mainstay of treatment.

POI is associated with a delayed diagnosis, dissatisfaction with the diagnostic process, variation in care received and suboptimal care. The 2024 POI guideline was developed to provide guidance on the diagnosis and management of POI, involving a partnership between the European Society for Human Embryology and Reproduction, American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), Monash University Centre for Research Excellence-Women’s Health in Reproductive Life (CRE-WHiRL) and the International Menopause Society (IMS), with an international expert guideline development group. The guideline contains 40 key questions with 145 recommendations based on the best available evidence from research or clinical consensus and forms the basis for this article.1

Diagnosis

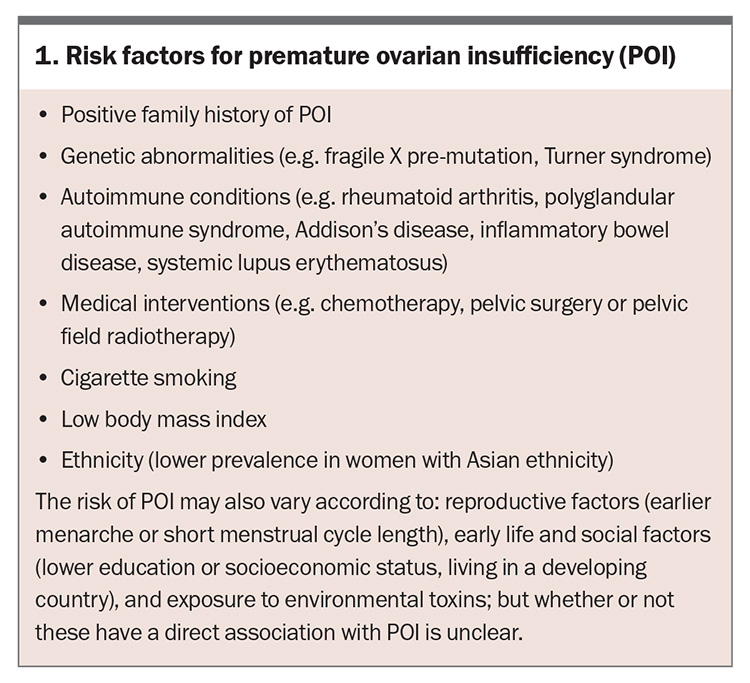

The clinical presentation of POI varies; however, POI should be considered in women younger than 40 years of age with a presentation of four months or more of menstrual disturbance. Secondary amenorrhoea is most common, although primary amenorrhoea may occur. Symptoms of oestrogen deficiency may or may not be present and are usually absent in women with primary amenorrhoea. Women may also present with primary or secondary infertility. Risk factors for POI include a positive family history, having a known genetic cause of POI or an autoimmune condition, cigarette smoking and medical interventions, such as chemotherapy, pelvic surgery or radiotherapy (Box 1). Symptoms and signs associated with an underlying cause of POI (e.g. Turner syndrome, autoimmune disease or cancer) may also be present. Diagnosis is often delayed because the patient or clinician may not consider POI as a potential cause.

Guideline recommendation: Healthcare professionals should consider and exclude the diagnosis of POI in women aged less than 40 years who have amenorrhoea/irregular menstrual cycles or oestrogen- deficiency symptoms.1

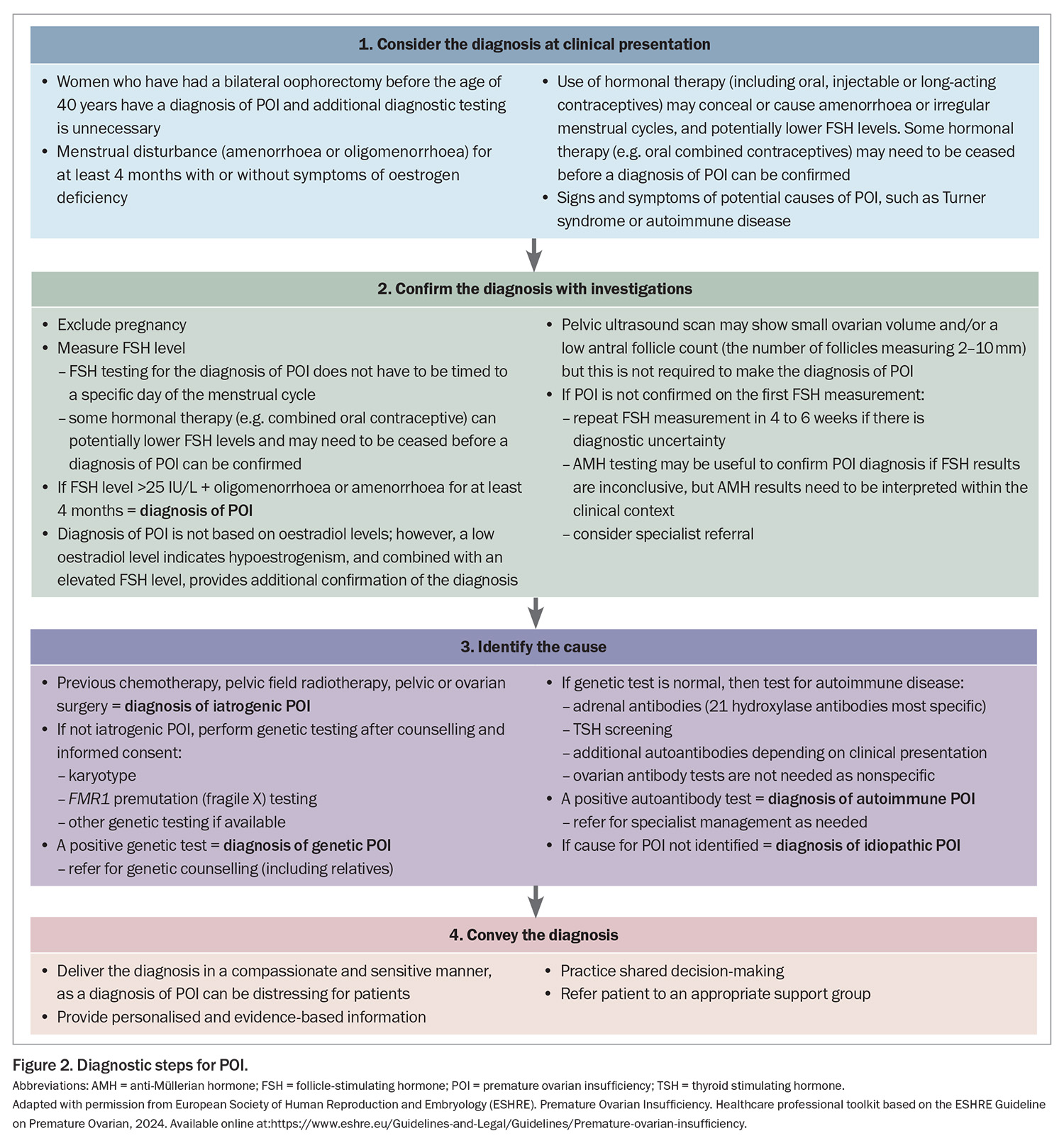

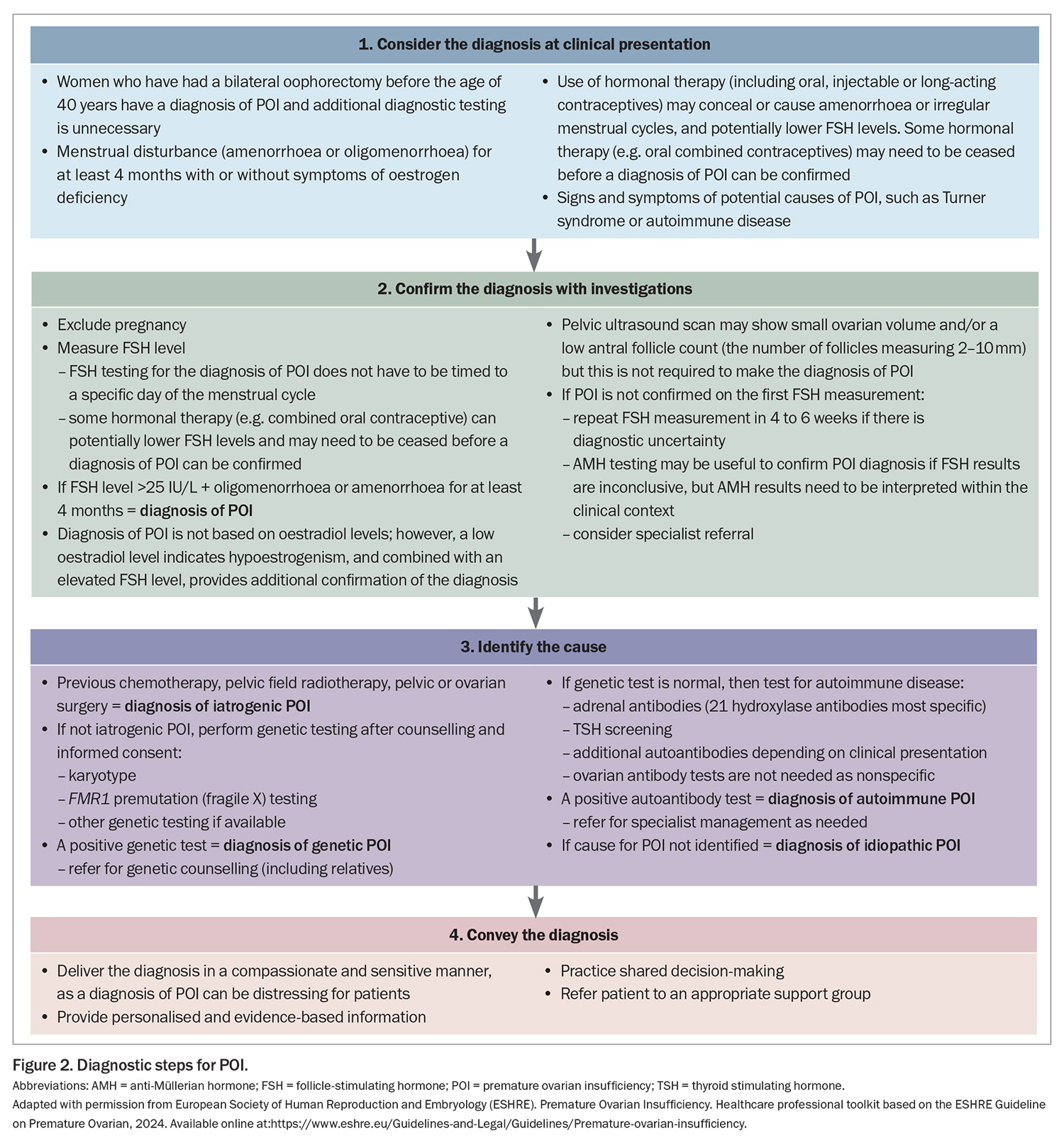

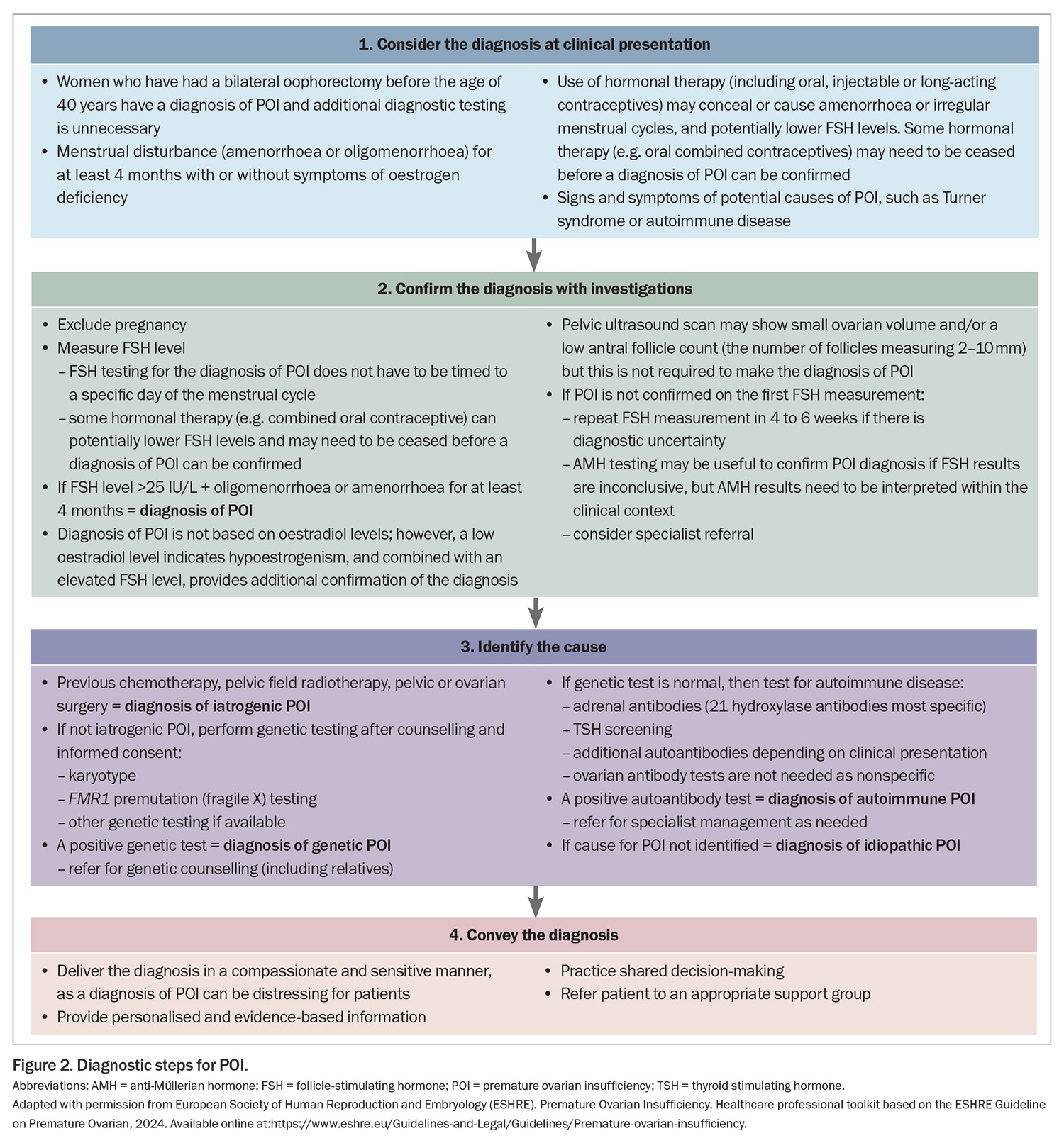

If a woman presents with at least four months of oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea and POI is suspected, it can be diagnosed if the FSH level is elevated (>25 IU/L) (Figure 2). A second elevated FSH level is no longer needed to confirm the diagnosis, as recommended in previous guidelines, as this may contribute to a delayed diagnosis. If a POI diagnosis remains unclear after the initial FSH measurement, the FSH measurement should be repeated after four to six weeks or anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) testing can be considered; however, AMH testing is not recommended as the primary diagnostic test for POI. Specialist referral may be helpful in this scenario. FSH or AMH testing is not required in women who have bilateral oophorectomy before the age of 40 years because they automatically have a diagnosis of POI.

Guideline recommendation: Healthcare professionals should diagnose POI based on the presence of spontaneous amenorrhoea or irregular menstrual cycles and biochemical confirmation.1

Once a diagnosis of POI is confirmed, the next step is to identify the cause of POI (Figure 2); specialist referral may be needed. The cause of POI may be iatrogenic or non-iatrogenic (Box 2).

The risk of iatrogenic POI depends on several factors, including the patient’s age, type and dose of chemotherapy, and dose and field of radiotherapy. In cases of non-iatrogenic POI, a genetic cause is identified in 7 to 35% of patients and includes chromosomal anomalies and specific gene variants. More than 100 genes have been implicated in causing sporadic or syndromic POI.2,3 These genes are involved in: DNA and meiosis repair; metabolism and mitochondrial functions; ovarian and follicle growth and development; coding for hormone receptors; oocyte growth factors; immune function; and RNA metabolism and translation such as FMR1. However, only karyotype and FMR1 (fragile X) premutation testing are currently routinely available in Australia. Autoimmune disorders, such as Addison’s disease, autoimmune thyroid disease and rheumatoid arthritis, are more frequent in women with POI than in the general population, and non-iatrogenic POI is more frequent in women with certain autoimmune disorders. However, most women with non-iatrogenic POI do not have an identified cause for POI and the term idiopathic POI is applied. This may change over time with increasing availability of specific genetic testing.

A diagnosis of POI can be distressing and women may experience a range of emotions. Factors that can lessen the negative impact of POI on quality of life include social support (family, friends and peer to peer) and counselling. Compassionate clinicians, prompt and sensitive revelation of the diagnosis, individualised care, timely provision of information, sufficient time to answer questions and continuity of care are also necessary.4 The implications for relatives should also be considered including referral for fertility preservation. Codesigned consumer information sheets and the app ASK Early Menopause based on the POI guideline are available to inform women and support self-management (Figure 3 and Box 3).

Management

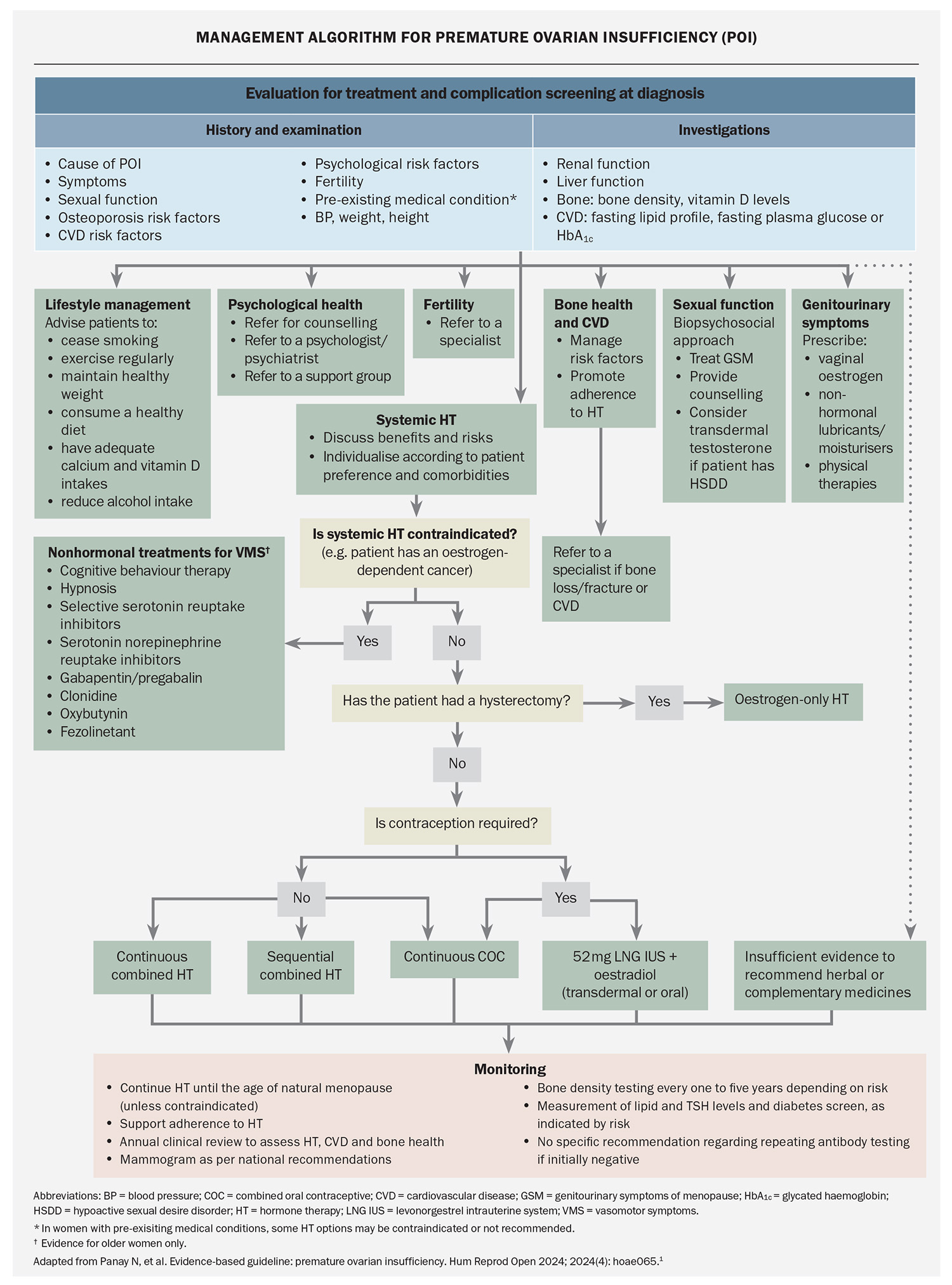

Once a diagnosis of POI is made, comprehensive evaluation is required to screen for and address:

- oestrogen-deficiency symptoms

- psychological health

- sexual function

- risks of long-term consequences of POI, such as osteoporosis and CVD

- appropriate hormone therapy options

- fertility concerns

- underlying causes of POI, such as Turner syndrome, autoimmune disease or cancer.

Because of the complexity of the issues associated with POI and the need for lifelong monitoring and holistic care, shared care between the GP, multidisciplinary specialists and allied health is usually required.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for women with POI and is recommended for all women with POI to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality, even if no oestrogen-deficiency symptoms (e.g. hot flushes) are present (Flowchart). Hormone therapy preserves bone and cardiovascular health and cognitive function, and increases life expectancy.1 It also improves sexual function, treats symptoms of oestrogen deficiency and can induce puberty. Delayed initiation and nonadherence are associated with bone loss and increased risk of CVD. Shared decision-making is recommended when prescribing each component of hormone therapy with consideration of patient preference, contraceptive needs and presence of comorbidities.

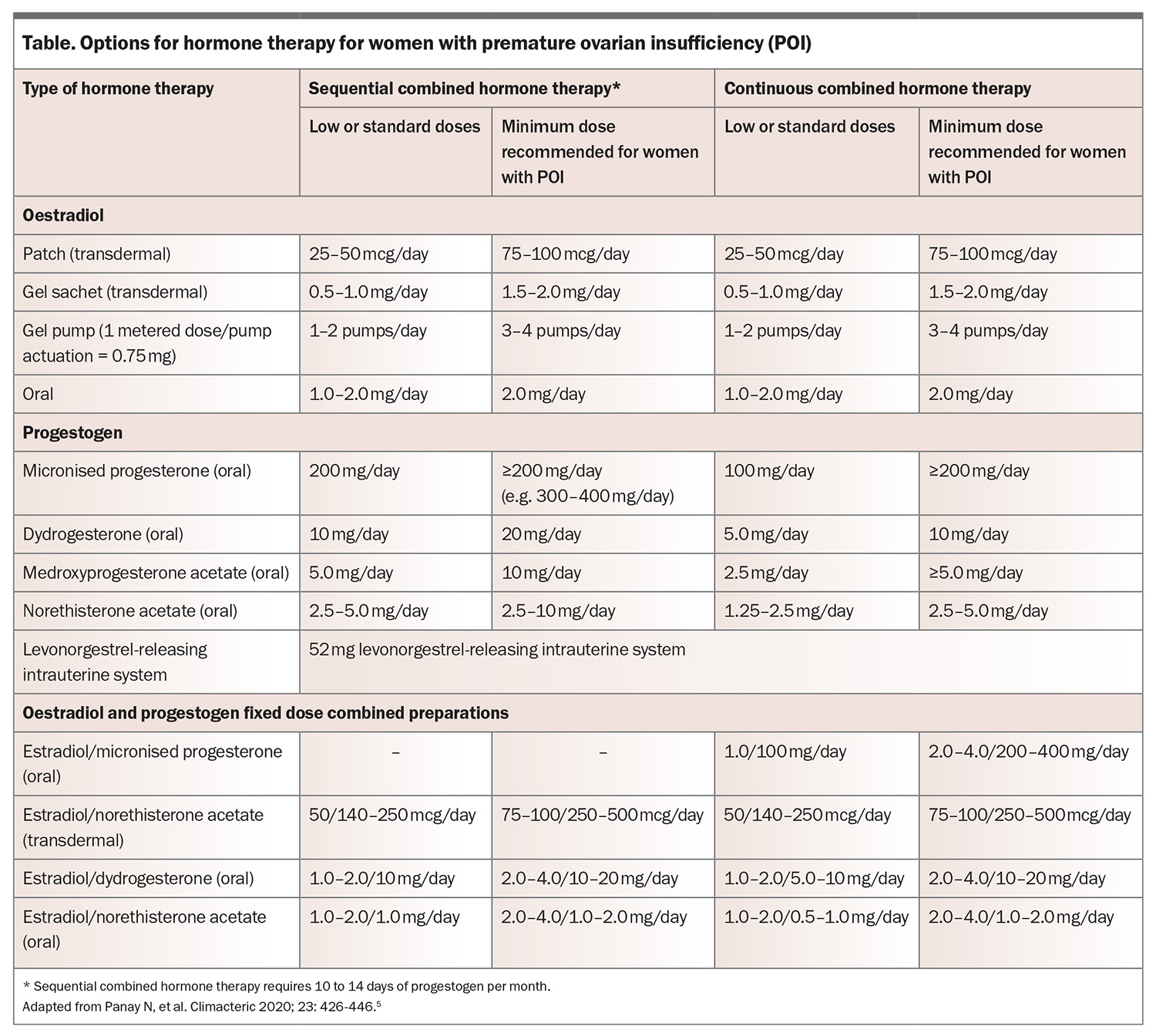

When prescribing hormone therapy for women with POI, the general principles used for prescribing hormone therapy for menopausal women aged older than 40 years still apply (e.g. combined oestrogen and progestogen therapy is required if the uterus is present). However, higher doses of oestrogen are needed compared with usual menopause to maintain bone density. At least 2 mg oral estradiol daily or 100 mcg transdermal patch or equivalent should be prescribed. If a higher oestrogen dose is used then a higher progestogen dose is recommended to avoid endometrial hyperplasia, although evidence specific to POI is limited (Table).

The usual contraindications to hormone therapy (such as oestrogen-positive breast cancer) also apply and specialist referral may be needed in complex cases (e.g. history of migraine with aura, POI following bilateral oophorectomy to reduce the risk of cancer if BRCA gene-positive or specific gynaecological cancers). Nonhormonal therapies for managing vasomotor symptoms may be considered if hormone therapy is contraindicated;1 however, these alternative therapies may not offer bone and cardiovascular protection and other primary prevention advantages. Individuals requiring pubertal induction should be referred to a specialist. The combined oral contraceptive should not be used for pubertal induction.

Guideline recommendation: Hormone therapy is recommended for women with POI until at least the usual age of menopause for primary prevention to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality, whether or not there are oestrogen-deficiency symptoms.1

Contraception

Women with spontaneous POI have a 5% lifetime chance of natural pregnancy, usually within the first few years postdiagnosis.1 Hormone replacement therapy is not a contraceptive and oestradiol combined with the 52 mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or the combined oral contraceptive (COC) should be considered if contraception is required. If the COC is used, then a continuous or extended regimen is recommended to provide continuous oestrogen therapy and avoid bone loss. It is uncertain whether the oestrogen doses in the 1.5 mg estradiol or 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol COC are adequate to maintain bone health in women with POI because studies have mainly involved 2 mg estradiol hormone therapy preparations or the 30 mcg ethinyl estradiol COC.

Psychological health

Women with POI report lower psychological wellbeing, lower quality of life, negative body image and lower self-esteem, with increased anxiety and depression, compared with women in the general population. Multiple factors may contribute to this including age at diagnosis, cause of POI, comorbidities especially infertility, patient experience and degree of social support. Psychological health screening and support should be offered to all women with POI.

Guideline recommendation: Personalised care, including psychological support, should be accessible to women with POI.1

Fertility

Infertility is a major cause of psychological distress and impaired quality of life in women with POI. Women who wish to conceive should be advised that oocyte or embryo donation is the best treatment and a referral to an infertility specialist is recommended for these women.

Guideline recommendation: Women with POI should be informed that there are no interventions that have been reliably shown to increase ovarian activity and natural conception rates.1

Monitoring

Regular review, at least annually, is recommended addressing psychological health, symptoms, sexual health, individualised chronic disease risk, adherence to therapy and any specific issues associated with the cause of POI (Figure 2).

Lifestyle behaviours to promote musculoskeletal health are recommended for women with POI, same as for women with usual age of menopause, such as adequate calcium and vitamin D intakes, weight-bearing and resistance exercise, and cessation of smoking. Bone densitometry is recommended at the time of diagnosis and should be repeated every one to three years if osteoporosis risk factors or low bone density (Z-score ≤2.0) are present at diagnosis. If bone density is normal at the time of diagnosis and hormone therapy adhered to, then bone densitometry can be repeated at five years. Specialist referral may be needed if a fragility fracture or a decrease in bone density occurs despite adequate oestrogen therapy.

The frequency of measurement of fasting lipid levels and diabetes screening after the initial screening at the time of diagnosis should be based on the presence of hyperlipidaemia, hyperglycaemia, other cardiometabolic risk factors (e.g. obesity) or global cardiovascular risk. Specialist referral may be considered if there is evidence of accelerated CVD risk requiring further investigations for risk stratification and appropriate hormone therapy in this setting.

Osteoporosis risk calculators, such as Fracture Risk Assessment Tool, and CVD risk calculators are not validated for women aged younger than 40 years.

Guideline recommendation: When women with POI reach the age at which usual menopause occurs, healthcare professionals should consider the need for continued hormone therapy based on a personalised risk–benefit assessment and current evidence.1

Conclusion

POI, defined as loss of ovarian function before the age of 40 years, has significant psychological and physical impacts including an increased risk of multimorbidity. The 2024 updated POI guideline highlights the importance of considering POI in any woman presenting with oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea to facilitate a prompt diagnosis delivered in a sensitive manner. Once diagnosed, a comprehensive assessment should follow, with initiation of personalised hormone therapy, recommended until at least the usual age of menopause, and ongoing monitoring. Providing information supports self-management and improves quality of life, and codesigned resources are available for both consumers and healthcare professionals. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Associate Professor Vincent has received travel and speaker honoraria from Besins and Theramex, consulting fees from Theramex and Astellas, nonrestricted research funding from Amgen, and research funding from the Australian government: NHMRC, MRFF, CRE-WHiRL. Associate Professor Ee: None.

References

1. Panay N, Anderson RA, Bennie A, et al. Evidence-based guideline: premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod Open 2024; 2024(4): hoae065.

2. Touraine P, Chabbert-Buffet N, Plu-Bureau G, Duranteau L, Sinclair AH, Tucker EJ. Premature ovarian insufficiency. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2024; 10: 63.

3. Van Der Kelen A, Okutman Ö, Javey E, et al. A systematic review and evidence assessment of monogenic gene–disease relationships in human female infertility and differences in sex development. Hum Reprod Update 2022; 29: 218-232.

4. McDonald IR, Welt CK, Dwyer AA. Health-related quality of life in women with primary ovarian insufficiency: a scoping review of the literature and implications for targeted interventions. Hum Reprod 2022; 37: 2817-2830.

5. Panay N, Anderson R, Nappi R, et al. Premature ovarian insufficiency: an international menopause society white paper. Climacteric 2020; 23: 426-446.