Managing obesity – looking beyond lifestyle interventions

Most people in Australia are overweight or have obesity. Obesity and its complications result in excess morbidity and mortality and a reduced quality of life, as well as a substantial financial burden to people and healthcare systems. Effective treatment options for obesity are available, and promising new therapies are under investigation in clinical trials.

- Almost one in three Australian adults has obesity.

- Effective treatments for obesity are available, which reduce morbidity and improve peoples’ health and quality of life.

- When the treatment goals are not met or are unlikely to be met by lifestyle interventions alone, medications and surgical management should be considered.

- GPs play a key role in supporting patients to manage obesity.

Obesity is a medical condition that heightens the risk of other health issues, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension. This article provides an overview of current and emerging pharmacological and surgical management approaches for obesity.

What is obesity?

Obesity refers to abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to a person’s health.1 A body mass index (BMI) greater than

30 kg/m2 is also used to define obesity, although the BMI alone does not indicate a person’s health status. Obesity is a complex chronic condition that develops in genetically predisposed people in response to several (predominantly environmental) factors.2

Why is it important to treat obesity?

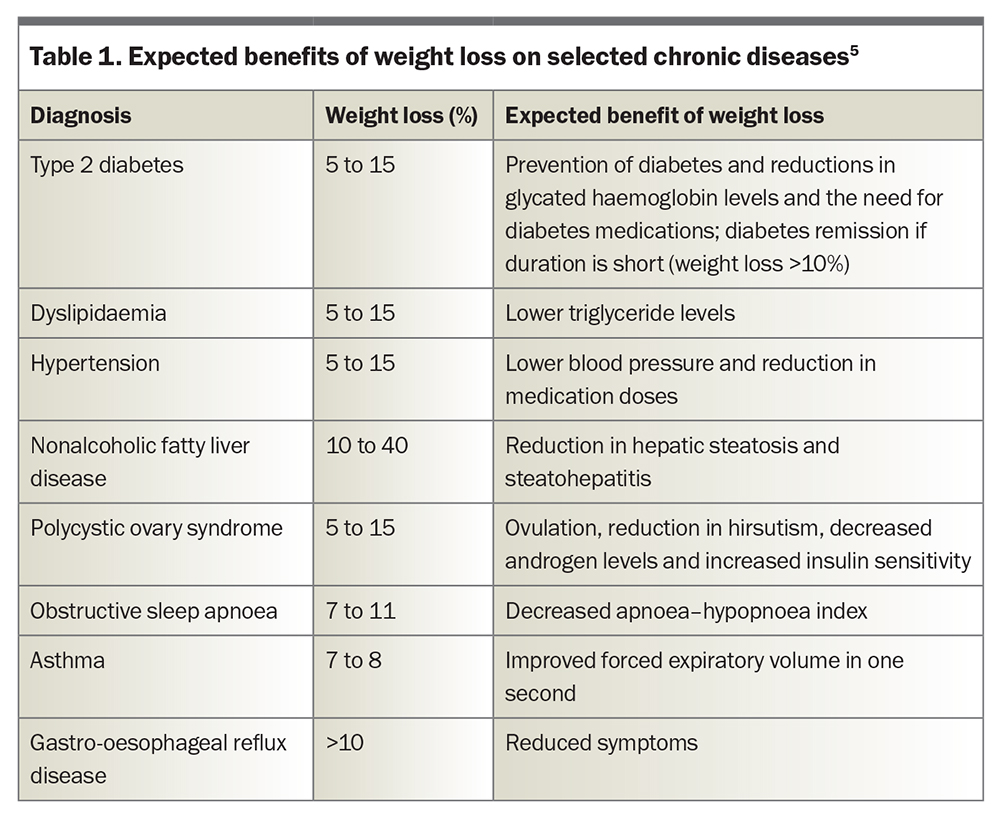

Obesity affects almost one-third (31%) of adults in Australia and is the second largest contributor to the country’s burden of disease, primarily because of its numerous complications.3,4 Much of the adverse impact of obesity on health and quality of life can be reduced with weight loss; hence, effective treatment is critical (Table 1).5 Loss of just 5% of the original body weight reduces the risk of progression to type 2 diabetes by more than 50% in people with impaired glucose tolerance, as well as improving blood pressure and triglyceride levels.6 Greater weight loss (in the order of 10 to 25%) has progressive benefits, including improvements in the control (and potentially remission) of type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, obstructive sleep apnoea, stress urinary incontinence and symptoms of osteoarthritis, and improvements in health-related quality of life.7 Until recent years, most interventions for obesity apart from bariatric surgery were expected to achieve sustained weight loss of less than 5%, but an increasing number of effective nonsurgical approaches is becoming available.8

What role do GPs play?

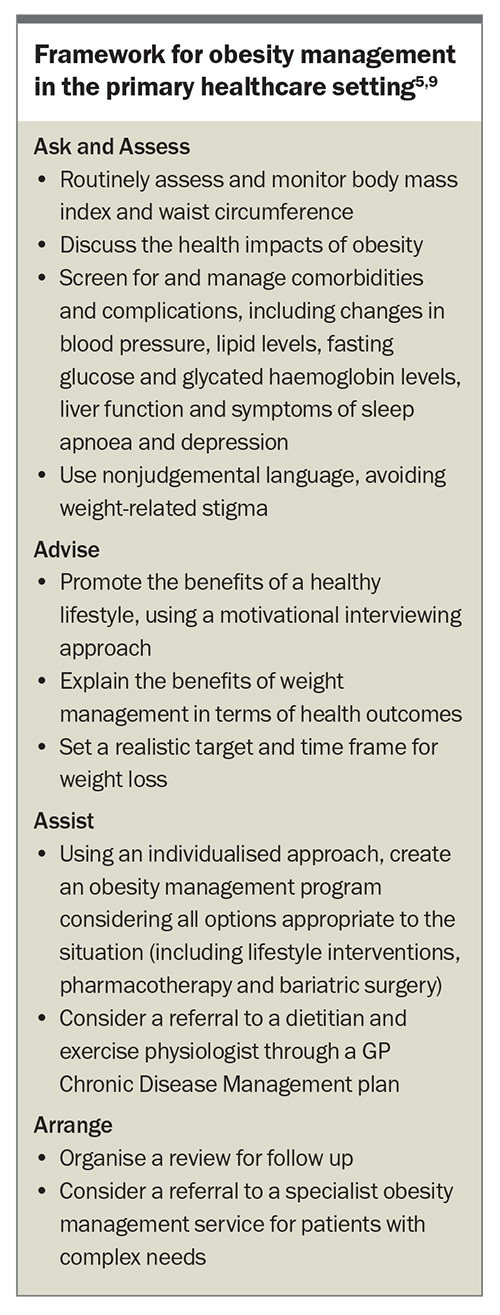

Obesity requires lifelong monitoring and management. GPs are essential in establishing a diagnosis of obesity and in managing obesity at each stage of the treatment pathway. The 5 A’s framework is a guide to obesity management in the primary healthcare setting (Box).5,9 Specialised obesity services are scarce and often need to limit the care provided, such as for people with genetic obesity syndromes or severe complications; these services may also have long (more than one year) waiting times.10 Therefore, obesity often needs to be managed largely or entirely within the primary healthcare setting. With the benefit of an established therapeutic relationship, primary healthcare practitioners are ideally placed to advise and support behaviour change; discuss, initiate and adjust medications when needed; refer to additional clinicians and services (e.g. dietitian, exercise physiologist, psychologist, specialist physician or surgeon) where required; monitor progress; and address challenges that arise during obesity treatment. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm also provides guidance on the assessment and management of obesity in the primary healthcare setting.11

What lifestyle interventions are effective?

The main purpose of lifestyle interventions in obesity management is to reduce energy intake, optimise nutritional quality and increase physical activity. This can be accomplished via a variety of approaches, with no single dietary pattern showing superiority. An individualised regimen supported by a multidisciplinary team with frequent contact (14 or more sessions across six to 12 months) has been shown in clinical trials to be the most effective approach;9 however, this degree of allied healthcare support is not subsidised by Medicare.

Most people who lose weight with lifestyle interventions alone will regain weight in the longer term. The misconception that obesity is simply caused by poor lifestyle habits and inadequate motivation for behaviour change is common and leads to stigma. However, weight loss leads to an enduring biological response that results in an increased appetite and a reduction in total energy expenditure (more than expected for the loss of body mass). Interactions between biological, psychosocial and ‘obesogenic’ environmental factors make the maintenance of weight loss challenging for most people.

What pharmacotherapy is available?

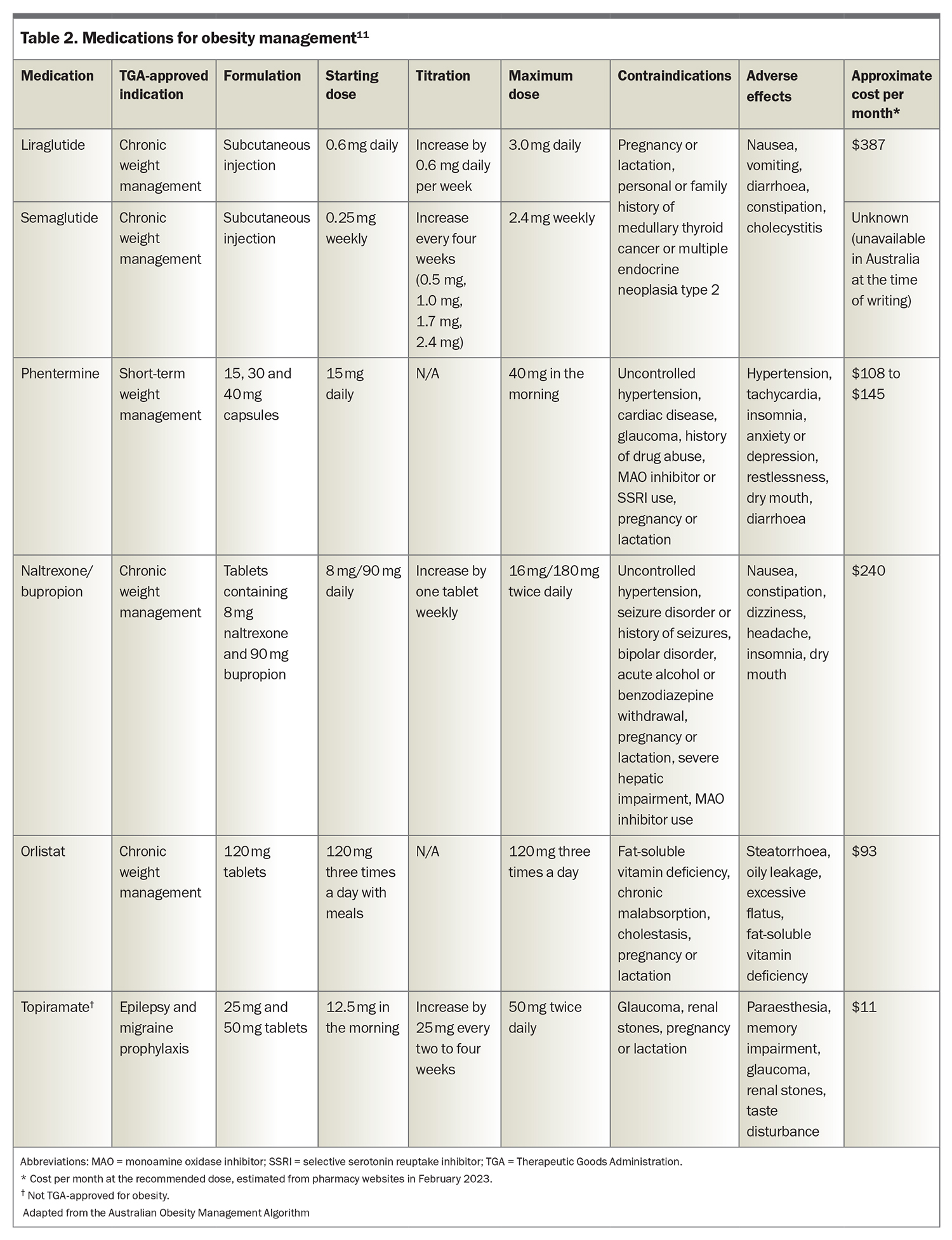

Five medications are approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for obesity management: liraglutide, semaglutide, phentermine, naltrexone-bupropion and orlistat (Table 2), although at the time of writing, semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly is not yet available in Australia.11 Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexone/bupropion and semaglutide are indicated for adults (18 years of age or older) with a BMI higher than 30 kg/m2, or higher than 27 kg/m2 with a weight-related complication. Phentermine is approved for adults and adolescents older than 12 years of age with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher. No medications are subsidised by the PBS for obesity management.

The choice of medication requires the consideration of a number of individualised factors, including the patient’s preference, severity of obesity, presence of obesity-related and unrelated medical conditions and the medication’s contraindications, adverse effect profile and costs. All the medications approved for obesity management are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

Two glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are currently TGA-approved for obesity management: liraglutide (dosage of 3.0 mg daily) and semaglutide (dosage of 2.4 mg weekly). Liraglutide (dosage of up to 1.8 mg daily) and semaglutide (dosage of up to 1.0 mg weekly) are also indicated for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, as is dulaglutide (dosage of 1.5 mg weekly). Semaglutide 1.0 mg weekly and dulaglutide are PBS-subsidised for management of diabetes in people with a glycated haemoglobin level greater than 53 mmol/mol (7.0%). In clinical trials for obesity management in people without diabetes, the mean total weight losses were 8% (vs 2.6% in the placebo group) in those taking liraglutide 3.0 mg daily for 56 weeks and up to 16% (vs 5.7% in the placebo group) in those taking semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly for 68 weeks.12,13

GLP-1 receptor agonists act via GLP-1 receptors. In the brain (particularly in the hypothalamus and hindbrain), they act to increase satiety and reduce hunger and food reward. In the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract, they slow gastric emptying, enhance insulin release in the presence of elevated glucose levels and reduce glucagon release.

Their beneficial effects on glycaemia make them particularly suitable for obesity management in people with (or at a high risk of) type 2 diabetes.13 At doses used to treat type 2 diabetes, some GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g. dulaglutide, liraglutide and semaglutide) reduce mortality and risks of cardiovascular and renal disease in patients with diabetes;14 however, these benefits have not yet been shown at the higher doses used to treat obesity in people without diabetes, who have lower risks of cardiovascular and renal disease.

The adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea and an increased risk of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. Nausea usually improves with continued therapy and can be minimised by starting the medication at a low dosage and gradually uptitrating.

Phentermine

Phentermine is a sympathomimetic agent that stimulates the release of noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin in several areas of the brain to reduce hunger and reward-related eating. It is indicated as a ‘short-term adjunct’ in a medically monitored obesity management program, with patients requiring medical review within three months. The weight loss within 12 weeks is typically five to 10%.15 Common adverse effects include tachycardia, hypertension, insomnia and dry mouth. Phentermine is contraindicated in people with cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled hypertension and those taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Phentermine is also not recommended in combination with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Naltrexone-bupropion

This combination of an antidepressant (bupropion) and opioid antagonist (naltrexone) acts in the hypothalamus and mesolimbic reward system to reduce hunger and food cravings. In a 56-week randomised trial, naltrexone-bupropion resulted in a mean weight loss of 6.1% (compared with 1.3% in the placebo group).16

The adverse effects include nausea, headache, dizziness, insomnia and dry mouth. Naltrexone-bupropion is contraindicated in patients with a history of seizures or bipolar disorder and in those using opioid medications. Several potential drug interactions are relevant when prescribing naltrexone-bupropion, particularly those involving cytochrome P450 enzyme activity, including a consideration of dose reductions of medications metabolised by CYP2D6 (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, because of CYP2D6 inhibition by bupropion) if prescribed concurrently.

Orlistat

Orlistat reduces gastrointestinal fat absorption by inhibiting pancreatic and gastric lipases. Unlike other obesity medications, orlistat is not systemically absorbed, having only local action in the gut lumen. Weight loss of about 5% is expected after one year of treatment.17

The safety and modest efficacy of orlistat have been shown in randomised trials of up to four years’ duration,although the adherence to treatment is poor, largely because of its gastrointestinal adverse effects.17 Common adverse effects include steatorrhoea, oily stools and flatulence. The absorption of fat-soluble vitamins may be reduced by orlistat; therefore, a multivitamin should be advised. Orlistat has a weight loss-independent effect on lowering LDL (by 28% compared with that by lifestyle interventions).18

Other agents

Topiramate

Topiramate is approved for the treatment of epilepsy and the prevention of migraine. It is commonly used off-label for obesity management, although the drug’s mechanism of action for weight loss is unclear. In the United States (but not in Australia), a combination of extended-release topiramate and phentermine is approved for obesity management. Meta-analyses of data from randomised controlled trials of topiramate for obesity suggest weight loss of about 5% compared to that with placebo.19,20 The adverse effects include gastrointestinal disturbances, difficulties concentrating, paraesthesia, depression, teratogenicity and (rarely) closed-angle glaucoma.

Tirzepatide

Tirzepatide is a dual agonist that acts at GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptors. It is TGA-approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes at dosages of 5, 10 and 15 mg once weekly but is not yet available in Australia at the time of writing. Tirzepatide is the first medication to show a mean weight loss of more than 20% in clinical trials for obesity management, and regulatory assessment for an obesity indication is expected to be sought in 2023. In a phase 3 clinical trial, participants taking tirzepatide 5, 10 and 15 mg achieved weight loss of 15%, 20% and 21%, respectively, after 72 weeks of treatment, compared with 3% with placebo.21 The adverse effects are predominately gastrointestinal, with a profile similar to that of GLP-1 receptor agonists.

When should pharmacotherapy be reviewed?

Patients should be monitored at least monthly for the first three months after initiating pharmacotherapy to assess safety and efficacy and review the need for dose titration.5 Early weight loss is predictive of longer-term weight loss; hence, weight loss of less than 5% after three months at the recommended dose requires a change in the treatment strategy.5 It is worth noting that if a medication is initiated to prevent or minimise weight regain (rather than to induce weight loss), weight stability (rather than continued weight gain) may still indicate a beneficial effect. Weight regain is likely after cessation of pharmacotherapy;22 therefore, long-term treatment is likely to be required (as for most chronic diseases), although data on the long-term efficacy and safety of obesity medications are currently lacking.

What is the role of bariatric/metabolic surgery?

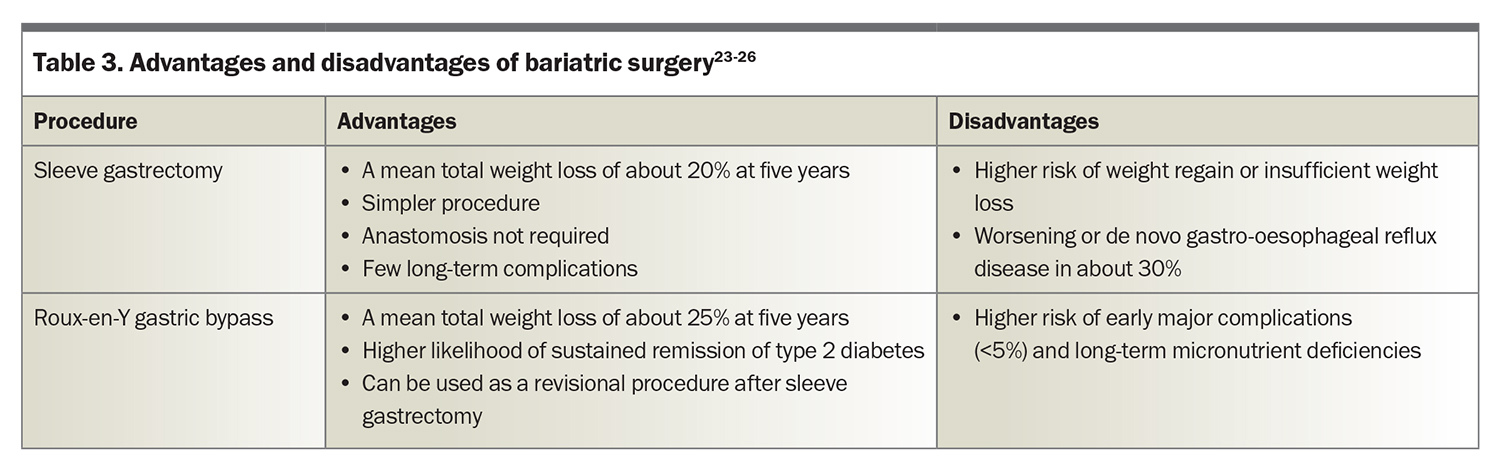

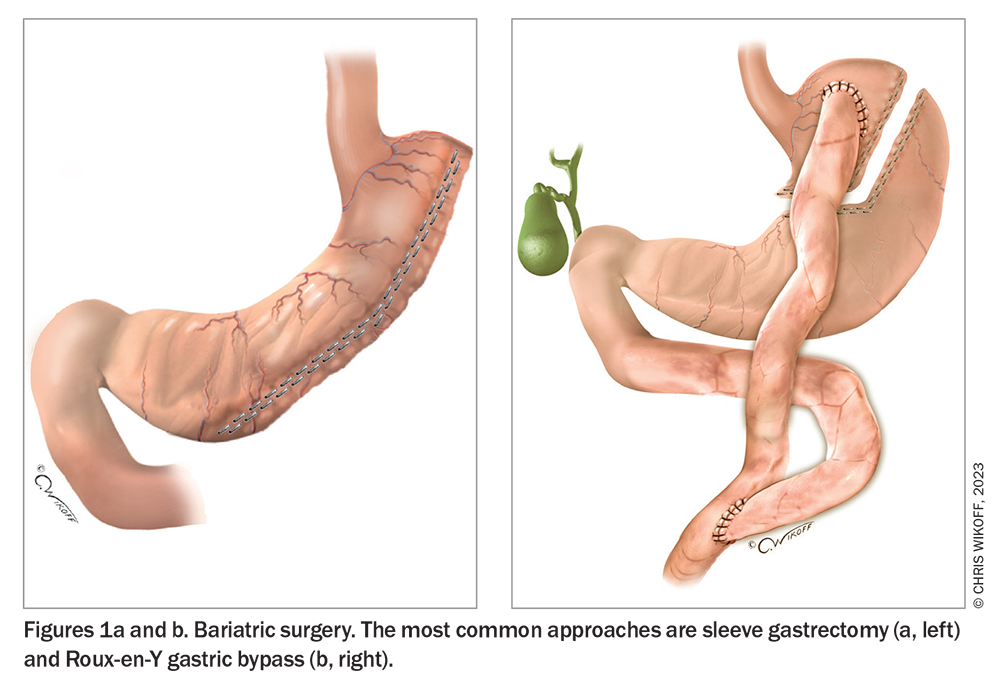

More than 40,000 individuals are estimated to undergo bariatric surgery each year in Australia.23 The most common operations are sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) (Table 3) (Figure 1), both of which help achieve substantial, sustained weight loss.23-26 Compared with sleeve gastrectomy, RYGB results in greater mean weight loss (at five years, around 25% after RYGB and 19% after sleeve gastrectomy in an observational cohort study [n = 65,000]) with a higher risk of major complications (at 30 days, 5.0% after RYGB and 2.6% after sleeve gastrectomy).24 Substantial weight regain, defined as regain to within 5% of pre-operative weight, occurs in fewer than 5% of patients after RYGB and in around 10% of patients after sleeve gastrectomy.27

Australian guidelines recommend that bariatric surgery be considered in patients with the following BMIs and presentations:

- BMI 40 kg/m2 or higher

- BMI 35.0 to 39.9 kg/m2 and comorbidities that may improve with weight loss

- BMI 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2, suboptimal control of type 2 diabetes and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.9

International guidelines were updated in 2022 to recommend bariatric surgery for people with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or higher, regardless of the presence, absence or severity of obesity-related conditions.28 Surgery should not be viewed only as a last resort for those in whom other obesity treatments have ‘failed’. For example, in patients with suboptimal glycaemic control on maximum medical management of type 2 diabetes, early referral to surgery should be considered. Access to bariatric surgery is limited and inequitable because of a lack of services, particularly in the public sector,with about 90% of bariatric surgeries occurring in the private healthcare system in Australia.29,30

A multidisciplinary team approach is imperative to assess the potential benefits and risks of bariatric surgery for each patient before surgery, as well as for preoperative preparation and postoperative follow up. After bariatric surgery, patients require lifelong nutritional supplementation, monitoring and ongoing support, although guidelines differ in terms of specific recommendations.25,31

What nonsurgical procedures are available?

Endoscopic insertion of a fluid- or air-filled intragastric balloon is a nonsurgical option for obesity management. This is a temporary procedure, with the balloon removed after around six months (depending on the specific product). This procedure aims to reduce food intake by reducing gastric capacity and delaying gastric emptying. Weight loss achieved in clinical trial settings is about 4% greater compared with that in lifestyle intervention groups after three to six months.32 Longer-term data are scarce. The adverse events include nausea, abdominal pain, deflation and (rarely) gastric perforation.

Conclusion

The goals of obesity management are to improve a person’s health and quality of life. Many patients will not achieve the goals of treatment using lifestyle interventions alone. Several obesity medications and bariatric surgeries are available. The latest generation of medications is associated with mean weight losses that are close to the magnitude seen with bariatric surgery. However, there are inequities in accessibility at every stage of obesity care. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Wootton: None. Associate Professor Sumithran’s institution received support from the National Health and Medical Research Council. She was a participant of a not-for-profit, investigator-initiated study involving dietary intervention sponsored by the University of Adelaide, and a Council Member at the ANZ Obesity Society (2017-2022). She is a member of the leadership group at the Obesity Collective, and a coauthor on manuscripts with medical writing services provided by Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly.

References

1. World Health Organization. Obesity. WHO; 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity (accessed April 2023).

2. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 254-266.

3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National health survey: first results. ABS; 2018. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/national-health-survey-first-results/latest-release (accessed April 2023).

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Impact of overweight and obesity as a risk factor for chronic conditions. Australian Burden of Disease Study series

no.11. Cat. no. BOD 12. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/impact-of-overweight-and-obesity-as-a-risk-factor-for-chronic-conditions/summary (accessed April 2023).

5. Schutz DD, Busetto L, Dicker D, et al. European practical and patient-centred guidelines for adult obesity management in primary care. Obes Facts 2019; 12: 40-66.

6. Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 2102-2107.

7. Tahrani AA, Morton J. Benefits of weight loss of 10% or more in patients with overweight or obesity: a review. Obesity 2022; 30: 802-840.

8. Rucker D, Padwal R, Li SK, Curioni C, Lau DC. Long term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: updated meta-analysis. BMJ 2007; 335: 1194-1199.

9. National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children in Australia. NHMRC; 2013. Available online at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/clinical-practice-guidelines-management-overweight-and-obesity (accessed April 2023).

10. Atlantis E, Kormas N, Samaras K, et al. Clinical obesity services in public hospitals in Australia: a position statement based on expert consensus. Clin Obes 2018; 8: 203-210.

11. Markovic TP, Proietto J, Dixon JB, et al. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm: a simple tool to guide the management of obesity in primary care. Obes Res Clin Pract 2022; 16: 353-363.

12. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 11-22.

13. Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, et al. Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: The STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 1403-1413.

14. Sattar N, Lee MMY, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021; 9: 653-662.

15. Kang JG, Park CY, Kang JH, Park YW, Park SW. Randomized controlled trial to investigate the effects of a newly developed formulation of phentermine diffuse-controlled release for obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010; 12: 876-882.

16. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 595-605.

17. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, Sjöström L. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 155-161.

18. Shi Q, Wang Y, Hao Q, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2022; 399: 259-269.

19. Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Pinto LC, Canani LH, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL. Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2011; 12: e338-e347.

20. Lei XG, Ruan JQ, Lai C, Sun Z, Yang X. Efficacy and safety of phentermine/topiramate in adults with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 2021; 29: 985-994.

21. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 205-216.

22. Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: the STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab 2022; 24: 1553-1564.

23. Dona SWA, Angeles MR, Nguyen D, Gao L, Hensher M. Obesity and bariatric surgery in Australia: future projection of supply and demand, and costs. Obes Surg 2022; 32: 3013-3022.

24. Arterburn D, Wellman R, Emiliano A, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of bariatric procedures for weight loss: a PCORnet cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 741-750.

25. Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures - 2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg Obese Relat Dis 2020; 16: 175-247.

26. International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders. Bariatric surgery. IFSO; 2018. Available online at: https://www.ifso.com/bariatric-surgery (accessed April 2023).

27. Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in adults: a review. JAMA 2020; 324: 879-887.

28. Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): indications for metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022; 18: 1345-1356.

29. Aly A, Talbot ML, Brown WA. Bariatric surgery: a call for greater access to coordinated surgical and specialist care in the public health system. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 228-231.

30. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Weight loss surgery in Australia 2014–15: Australian hospital statistics. AIHW Cat. no: HSE 186. Canberra: AIHW; 2017. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/ahs-2014-15-weight-loss-surgery/summary (accessed April 2023).

31. O’Kane M, Parretti HM, Pinkney J, et al. British Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society Guidelines on perioperative and postoperative biochemical monitoring and micronutrient replacement for patients undergoing bariatric surgery - 2020 update. Obes Rev 2020; 21: e13087.

32. Kotinda APST, de Moura DTH, Ribeiro IB, et al. Efficacy of intragastric balloons for weight loss in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Surg 2020; 30: 2743-2753.