Polycystic ovary syndrome: towards personalised care for women in general practice

Many women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) expressed dissatisfaction with their diagnostic experience and the health care they received. This article summarises recommendations from the latest international evidence-based PCOS guideline and discusses available resources to help GPs provide personalised care to women with PCOS.

- Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) differ in adults and adolescents, with guidelines recommending against ovarian ultrasound in adolescents to avoid early overdiagnosis.

- It is important clinicians acknowledge and prioritise the main concerns women with PCOS have, noting these differ between individuals and across the lifespan.

- Clinicians should also be vigilant in screening for emotional wellbeing and metabolic health in affected women.

- Clinicians should provide women with PCOS with evidence-based educational resources and mobile health apps recommended by the PCOS guideline.

- Women with PCOS should be advised about healthy lifestyle using specific, measureable, achievable, realistic, timely (SMART) goals, focused on prevention of excess weight gain.

- Combined oral contraceptive pills and metformin are effective pharmacological treatments for PCOS symptoms, with no preferred type of combined oral contraceptive pill and general safe prescribing recommendations applying in general practice. Antiandrogens have a more limited secondary role.

GPs have an important role to play and are on the front line of diagnosing and managing women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which is the most common endocrinopathy in women, affecting up to one in six women and one in four Indigenous women in Australia.1,2 However, management of PCOS is challenging given that it is heterogeneous in nature with reproductive, dermatological, metabolic and psychological manifestations.3 PCOS varies between individuals and across the lifespan. Women with PCOS are often frustrated by a delayed diagnosis, lack of information provision and inconsistent practice among healthcare providers.4,5

This article consolidates recommendations from the latest international guideline on the assessment and management of PCOS and discusses the available resources for GPs to support the delivery of evidence-based and personalised care for women with PCOS.6

How to diagnose PCOS

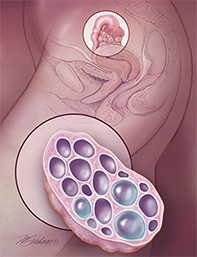

Although not universally present in all women with PCOS, insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism are the two main hormonal disturbances that contribute to the main features of PCOS, which are oligoamenorrhoea, hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical) and polycystic ovary morphology on ultrasound.3 The 2003 Rotterdam criteria are the internationally endorsed criteria for diagnosing PCOS and define PCOS as the presence of two out of three clinical features, after exclusion of secondary causes.7

However, use of the Rotterdam criteria in adolescents is controversial, with experts arguing it leads to over-diagnosis since oligomenorrhoea and multifollicular ovaries are common during puberty. The latest (2018) international PCOS guideline now recommends against ovarian ultrasound assessment in adolescents, with the diagnosis of PCOS needing the presence of both oligo-/amenorrhoea and hyperandrogenism.6 The definitions of each diagnostic criteria in both adults and adolescents are presented in Figure 1. It is important to note that in adolescents, the definition of oligomenorrhoea changes based on gynaecological age.6 This approach recognises the adolescent pubertal transition, but also gives clinicians confidence they can make the diagnosis at this lifestage. For adolescents with isolated persistent oligo-/amenorrhoea or hyperandrogenism who do not meet the criteria of PCOS, lifestyle intervention or combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs) may be initiated for symptom management with plans to withdraw COCPs for reassessment of PCOS in adulthood.

Secondary causes of menstrual disturbances and hyperandrogenism need to be considered. Hypothyroidism, hyperprolactinaemia and nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia should be excluded biochemically in all women. Biochemical evaluation can also be performed to check for hypothalamic amenorrhoea, if clinically suspected, in lean or underweight women who report excessive physical exercise. If hyperandrogenism is present, suspicion of a secondary cause may be needed, depending on rate of change of symptoms and/or signs and the severity or if out of context. Women can be screened for an androgen-secreting tumour, Cushing’s syndrome or acromegaly if there are suggestive clinical features. Relevant investigations are listed in Figure 1.

Providing information at diagnosis and optimising self-care

Only 15.6% of women with PCOS were satisfied with the information provided at diagnosis based on a national/international survey.4,6 Similar to other chronic diseases, self-management is vital to optimise health outcomes and this cannot be achieved without adequate education of affected women. Women with PCOS have a strong desire to be educated about the underlying hormonal imbalance and long-term risks of PCOS, as well as to be counselled about lifestyle management.4 Unfortunately, our current healthcare systems impose significant time constraints on GPs, limiting opportunity for long complex discussion that is needed for women with PCOS.

The PCOS guideline committee recognises the need for accessible evidence-based information resources, and huge efforts have been put into co-developing educational materials as part of the guideline translation. Resources include the mobile health app AskPCOS, infographics (on emotional wellbeing, fertility and pregnancy, lifestyle and treatment), videos and podcasts, and a PCOS consumer booklet, which explain PCOS pathophysiology, diagnosis, symptoms, long-term complications, lifestyle management, pharmacological treatment and family planning. Weblinks to these resources are provided in Table 1. This allows GPs to direct women to reliable, evidence-based educational material at diagnosis, while more detailed information can be explained at subsequent appointments based on a woman’s individual concerns.

In view of the growing popularity of mobile health apps, AskPCOS, an evidence-based PCOS mobile tool, was developed to provide trustworthy and reliable information to women with PCOS. The design and content are based on extensive consultations with women and GPs and provide personalised information based on women’s preferences and concerns.8 The app has features such as expert short videos, symptoms recording function, self-assessment quiz and a question prompt list to enable women to generate a targeted and limited personal list of questions to ask their GP.8 Currently, the app is available in English only (for both iOS and Android platforms), but translation into other languages is in process to maximise reach.

Lifestyle advice

Lifestyle modification (healthy eating and regular physical activity) is the cornerstone of PCOS management for the prevention of related weight gain and treatment of excess weight, as it improves the reproductive, metabolic and psychological features of PCOS. However, studies have revealed that lifestyle advice was only provided in a satisfactory manner to 11% of women with PCOS at diagnosis.4,6 Healthy lifestyle advice and a focus on prevention of weight are crucial and well placed in primary care for all women with PCOS who are within or above the healthy weight range, as they are predisposed to excess weight gain. It is often helpful to provide basic lifestyle advice to women with PCOS in a SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely) manner with clear goals and directions.9

Lifestyle advice can be prescribed to women based on their body mass index (BMI). In women who are within a healthy BMI range, weight maintenance and prevention of weight gain should be their treatment goal. Currently, evidence does not support any specific diet type in women with PCOS, therefore, general healthy eating recommendations should be given according to national dietary guidelines. Physical activity of a minimum of 150 min/week of moderate intensity or 75 min/week of vigorous intensity exercise, or an equivalent combination of both, should be prescribed.6 In women who have an elevated BMI, the treatment goal should be set as 5 to 10% loss of total body weight and prevention of weight regain. A dietary intake with 30% or 500 to 750 kcal/day energy deficit with 250 min/week of moderate intensity or 150 min/week of vigorous intensity exercise, or an equivalent combination of both, are required to achieve weight loss.6 Additionally, physical activity should be performed in at least 10 minute bouts for health benefits and muscle strengthening exercises are also recommended on two nonconsecutive days of the week.

Behavioural strategies such as goal setting, self-monitoring or problem solving, and use of fitness tracking devices or mobile apps, could further assist women to self-manage their lifestyle. GPs should have a low threshold to refer women who require additional support to optimise lifestyle to relevant allied healthcare professionals, such as dieticians, exercise physiologists or health coaches.6 To enable this, a GP co-designed care plan is available online to assist in care (Table 1).

Pharmacological treatments used in general practice

Discussion of specific fertility and obesity treatments in women with PCOS is beyond the scope of this article. Here, we focus on the three main pharmacological treatments for women with PCOS that are commonly used and safe to start in general practice. These are COCPs, metformin and antiandrogens (Table 2).

Combined oral contraceptive pills

COCPs are the first-line pharmacological treatment for women with PCOS who do not wish to conceive. Their mechanisms of action include direct suppression of ovarian androgen production and indirect suppression of androgen action via elevating hepatic sex hormone-binding globulin production. COCPs improve regularity of menses and biochemical and clinical hyperandrogenism (hirsutism or acne) and also protect against endometrial cancer.10 There is limited evidence for weight and metabolic health benefits with some concern about adverse potential metabolic effects, particularly in worsening of insulin resistance.10,11 However, it is important to note that there is no longitudinal evidence showing that COCPs increase the risk of type 2 diabetes in women with PCOS.12

Prescription of COCPs should follow the general population guidelines, starting with the lowest effective oestrogen dose (20 to 30 mcg ethinyloestradiol or equivalent), preferencing older generation progestins such as levonorgestrel and norethisterone that are associated with lower thromboembolic risk. Specific types or dose of estrogens or progestins or combinations of COCPs cannot currently be recommended in women with PCOS, with no clear greater benefits with any preparation. Indeed, preparations containing a higher dose of 35 mcg ethinyloestradiol in combination with cyproterone acetate should not be considered as first line treatment due to adverse effects and no clear evidence of increased benefit.6

Use of COCPs carries a higher risk for women who are over 35 years of age or have obesity, a history of migraine with aura, a high risk for a thromboembolic event (e.g. previous event or known thrombogenic mutations), multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease (e.g. history of ischaemic heart disease, stroke, hypertension), or a history of breast cancer or severe liver disease.6 If COCPs are contraindicated or not tolerated, progestin-only contraceptives or progestins used for 10 days every three months to induce a withdrawal bleed and protect the endometrium may be considered, although their efficacy for hyperandrogenism is limited.

Metformin

Metformin, an insulin sensitiser and off-label treatment for PCOS, is an effective therapy in addition to lifestyle management to manage metabolic features and weight gain and can be considered for menstrual regulation in women with PCOS who wish to conceive. A recently published overview of systematic reviews reported that in women with PCOS, metformin has beneficial metabolic effects, such as promoting weight loss and preventing weight gain, diabetes or prediabetes.10 Although some studies reported improvement in biochemical androgen levels, there is no apparent effect on clinical hyperandrogenism such as acne or hirsutism.10 The PCOS guideline suggests that metformin may offer greater benefit in women with PCOS who are at high metabolic risk (e.g. above healthy BMI, at risk for diabetes and high-risk ethnic groups).6 Gastrointestinal side effects are common although self-limiting, and with slow dose escalation, metformin is generally well tolerated.

Antiandrogens

COCPs and cosmetic measures (e.g. waxing, threading, laser) are indicated for managing clinical hyperandrogenism and should be trialed before using antiandrogens. The indication for antiandrogen therapy (e.g. spironolactone and cyproterone acetate) in women with PCOS is severe clinical hyperandrogenism (i.e. hirsutism or androgen-related alopecia). Overall, there is a lack of evidence to support the use of antiandrogens, with no specific type or dose able to be recommended for women with PCOS.13,14 The PCOS guideline considers antiandrogens as second-line treatment and recommends their use as an add-on therapy if COCPs alone fail to improve clinical hyperandrogenism after six to 12 months of use.6 Alternatively, if COCPs are contraindicated or poorly tolerated, antiandrogens could be considered but only if other effective forms of contraception are used. It is mandatory to use concomitant contraception with antiandrogens to avoid teratogenic effects and undervirilisation of a male fetus in the event of an unplanned pregnancy.6

Screening for emotional wellbeing and metabolic complications

Psychological associations of PCOS remain under-recognised by clinicians despite increasing evidence showing women with PCOS have increased risk of mood disorders, eating disorders or disordered eating, low self-esteem and poor body image.15 GPs often have a long-term, doctor–patient relationship, which builds trust and the ability to review patients more frequently for broader clinical features compared with specialists. Therefore, GPs are well placed to assess and monitor women’s emotional wellbeing and initiate treatment or refer the woman to a psychologist or psychiatrist if required. Recognising that screening of emotional wellbeing takes up time and resources, the PCOS guideline has provided some simple, brief questions for initial screening for anxiety, depression, body image and eating disorders (see Table 3). Further assessments using validated tools is recommended if screening questions are positive.6,16

Screening for metabolic complications includes regular weight measurement (in consultation and agreement with the woman and adapted for women with eating disorders) and blood pressure monitoring at least annually. Lipid profile should be assessed if women have overweight or obesity, and follow-up frequency is based on results and other cardiovascular risk factors. Diabetes screening should be performed on all women with PCOS at baseline and then reassessed every one to three years. The oral glucose tolerance test is more sensitive than measurement of fasting plasma glucose or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, and should be used in women with PCOS who are at high risk of diabetes (e.g. BMI >25 kg/m2, family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes, high-risk ethnicity) and before and during pregnancy.6

Integrated PCOS services

PCOS is complex and affects the biopsychosocial dimensions of a woman’s life. Currently, there are limited PCOS-dedicated services. Most services focus on infertility and are not able to meet women’s nonreproductive needs. There is a compelling need for an integrated PCOS model of care to address the multifaceted concerns of women with PCOS to improve their satisfaction, health outcomes and overall quality of life. Several integrated PCOS services are currently available in Australia to support GPs and assist with care of women with PCOS (Table 4). GPs can consider referring women with PCOS to these services to establish initial care plans. Individual specialty care can target specific features of PCOS, whereas GP care can ensure integration of care and management of the broader features of PCOS.

Conclusion

GPs have an important role in diagnosing and managing women with PCOS. Self-management is vital to optimise health outcomes and this cannot be achieved without adequate education of women with PCOS. There are now robust, co-designed evidence-based resources such as the international PCOS guideline, GP resources (such as PCOS GP tool and care plan) and consumer resources (such as AskPCOS app, infographics, webinars and online content) to assist with care of women with PCOS in general practice.

Lifestyle advice (healthy eating and regular physical activity) is the cornerstone of PCOS management for prevention of related weight gain and in treatment of excess weight, as this improves the reproductive, metabolic and psychological features of PCOS. COCPs, metformin and antiandrogens are the three main pharmacological treatments for women with PCOS, which are commonly used and safe to start in general practice. ET