A fitness instructor with low testosterone levels

A 51-year-old man with a low testosterone level complaining of loss of libido is diagnosed with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism by his GP. The patient works as a fitness instructor and has been taking supplements containing androgenic steroids. His case is discussed by an endocrinologist.

- When assessing men with suspected androgen deficiency, determine the nature and time course of symptoms, ask about puberty, testicular pathology, previous fertility and exposure to exogenous androgens.

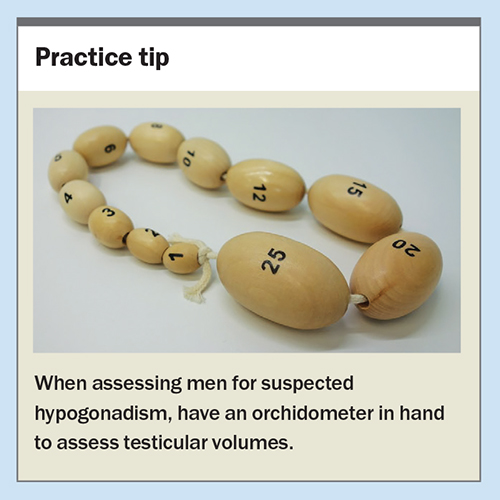

- Examine the distribution of body hair, muscle and fat, test visual fields, assess whether gynaecomastia is present and measure testicular volumes with an orchidometer.

- Men with organic hypogonadism have disorders of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland or testes resulting in reduced fertility and androgen deficiency.

- Abuse of androgenic steroids is becoming more frequent: the correct management is to stop exogenous androgens and allow the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis to recover.

Case scenario from the GP

Bill, 51 years old, presents to his GP complaining of lethargy in the absence of any infective symptoms. He also reports loss of libido, erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation, and is concerned about the loss of intimacy with his long-term female partner of 21 years. He is a fitness instructor at a local gym, and is concerned that he might be testosterone deficient, given similar complaints and diagnoses from clients at his workplace. His recent testosterone level (taken four months previously) was 4.1 nmol/L (reference range [RR], 11 to 40 nmol/L).

Bill has a past history of mild hypertension, which he is managing with lifestyle modifications of reducing his dietary intake of salt and regular cardiovascular exercise. He has no past medical conditions, and his routine screening is up-to-date and unremarkable. A mental health screen is unremarkable.

Bill is not taking any regular medications. He reports using multiple supplements over the past three years, and some of these contain testosterone. He is not taking opiates or glucocorticoids. On examination, he exhibits hypogonadism.

Investigations reveal normal results for full blood count, urea and electrolyte levels and renal and liver function tests. His C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are not elevated. Measurement of morning testosterone levels shows a low level of 3.2 nmol/L (RR, 11 to 40 nmol/L). His luteinising hormone (LH) level is 1.9 U/L (RR, 2 to 10 U/L), and prolactin, fasting lipids, glycated haemoglobin levels and iron studies are within normal limits.

A diagnosis of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism is made.

Discussion from an endocrinologist

What further assessment is required?

A more complete assessment of this case may change the diagnosis. The following questions should be considered. Bill is 51 years old; did he go through puberty normally? Does he have a history of testicular abnormalities or trauma? Has he fathered children? When did the symptoms of loss of libido, erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation, all of which may have causes other than androgen deficiency, appear?

Further assessment is needed of the supplements Bill has been taking, in the context of abuse of testosterone or other androgenic (anabolic) steroids.

The description ‘Bill exhibits hypogonadism’ should be more specific. What actual physical signs are present? Does Bill have a eunuchoid habitus (tall, slim, underweight, long limbs), gynaecomastia and small testes? Or does he have central adiposity and limited muscle mass but is otherwise normally virilised, with normal testicular volumes (see Practice tip)? Are his visual fields normal? If he is a regular gym attendee, is he abusing androgenic steroids? Does he have increased muscle mass? Are there abnormalities in the distribution of his body hair?

There is no mention of the patient’s weight, body mass index or waist circumference. Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) level was not included as part of biochemical testing. Central adiposity is often associated with reduced SHBG levels, and hence with lower total testosterone concentrations. Conversely, higher SHBG levels could be a marker of energy deficit due, for example, to excessive exercise and caloric restriction. Exogenous testosterone therapy lowers SHBG levels and raises haemoglobin levels and haematocrit (and reduces testicular volumes).

What differential diagnoses should be considered in this case?

With a normal LH level, and assuming he had a normal puberty and has normal testicular volumes, it is unlikely Bill has primary testicular impairment. From his history it does not appear that Bill is very stressed or depressed, nor is he taking opioids or glucocorticoids and, being a fitness instructor, it is unlikely he is obese – all of which may suppress hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular (HPT) axis function.

Bill’s normal iron studies results make haemochromatosis unlikely. Given his prolactin level is normal, the likelihood of a prolactinoma is low. Might Bill have a macroadenoma that is impeding normal anterior pituitary function, resulting in hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, possibly even panhypopituitarism (but not sufficiently large to cause pituitary stalk compression and elevation of prolactin)? Bill does complain of lethargy (but not of headache or visual field loss). The likelihood is not very high but it would be worth considering further evaluation, especially if there are additional indicators, such as postural hypotension, hyponatraemia or low early morning levels of cortisol or free thyroxine (T4) or triiodothyronine (T3).

What advice should be given regarding androgenic steroid use?

Abuse of androgenic steroids, including testosterone, is occurring with increasing frequency, reflecting misguided idealisation of an overly lean and muscular physique. If Bill’s gym supplements contain testosterone or other androgenic steroids, or if he has been using intramuscular androgenic steroid injections, his HPT axis could be suppressed. In this scenario, Bill should be advised to stop taking supplements containing testosterone or other androgenic steroids and avoid any exogenous testosterone or other androgenic steroids to enable his HPT axis to recover with time. Any further exposure to exogenous androgens would delay recovery.

What length of time is anticipated for recovery?

It may take up to 12 months to recover from sustained exposure to androgenic steroids. During this time, androgen deficiency symptoms may be experienced as transient hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (anabolic steroid withdrawal hypogonadism). It may be helpful to reassess testosterone levels three to six months after the last androgenic steroid exposure, with the warning that it might take 12 months (and possibly longer) for levels to return to the normal range. The expectation is that recovery will occur but serial testing over an extended period would be needed to document the time course.

How should this patient be managed?

In the absence of any specific indicators of pituitary disease, the first issues are to address Bill’s androgen abuse and provide him with encouragement and moral (not pharmacological) support to deal with anabolic steroid withdrawal hypogonadism. Further investigation for hypothalamic or pituitary disease causes of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (including MRI), could proceed if Bill’s HPT axis did not recover during follow up. Bill should be referred to an endocrinologist if there is diagnostic uncertainty or to confirm the diagnosis, and for assistance with management.

Would any additional pharmacotherapy be considered in this case?

Evidence is lacking to support the use of selective oestrogen receptor modulators, aromatase inhibitors or human chorionic gonadotrophin in the setting of anabolic steroid withdrawal hypogonadism and these are not recommended.

When would exogenous testosterone replacement be recommended?

Only if it is found that Bill in fact has hypothalamic, pituitary or testicular disease that has rendered him androgen deficient (organic hypogonadism), without reversible causes (e.g. prolactinoma treatable with cabergoline), would testosterone treatment be recommended. In that scenario, any fertility considerations need to be addressed first. Testosterone treatment would then be tailored to resolve the symptoms and signs of androgen deficiency, providing physiological concentrations of testosterone.

What testosterone treatments are available for men with proven organic hypogonadism?

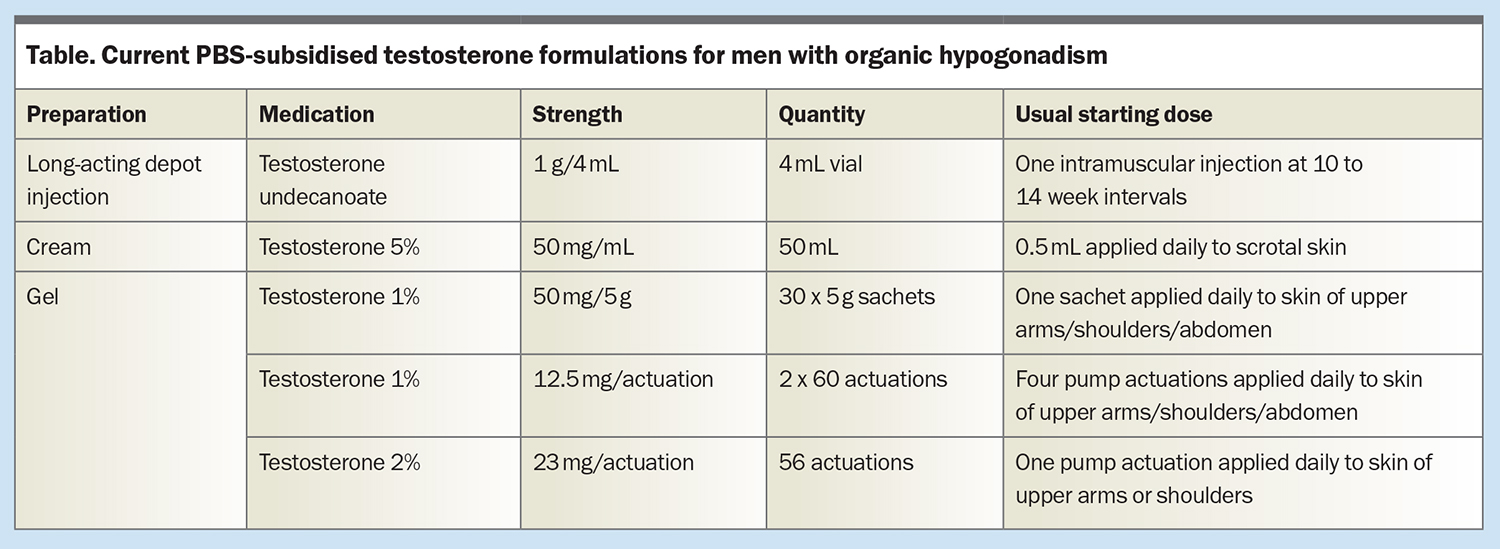

Current PBS-subsidised testosterone formulations in men with organic hypogonadism are long-acting depot intramuscular testosterone undecanoate (1 g/4 mL, long-acting depot injection, given at 10 to 14 week intervals); testosterone cream (5%, 50 mg/mL, usual starting dose 0.5 mL applied daily to scrotal skin); and testosterone gel (1%, 50 mg/5 g sachet or 12.5 mg per actuation, usual starting dose one 5 g sachet or four pump actuations applied daily to skin of upper arms, shoulders or abdomen; or 2%, 23 mg per actuation, usual starting dose one pump actuation applied daily to skin of upper arm or shoulder). Transdermal therapy should be applied to clean, dry and healthy skin. These options are summarised in the Table.

The advantages, disadvantages and precautions of these different testosterone formulations need to be discussed carefully with individual patients to guide their choices, and suitable efficacy assessments and monitoring regimens implemented (see Further reading). Referral to an endocrinologist is recommended for determination or confirmation of the diagnosis, or assistance with management of testosterone replacement therapy, and is part of the PBS-approval process.

Conclusion

Men presenting with symptoms of androgen deficiency require careful clinical assessment for any evidence of hypothalamic, pituitary or testicular disease. Abuse of androgenic steroids is occurring more frequently: this needs to be identified and managed correctly by cessation of exogenous androgens to allow the HPT axis to recover with time. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Lilly and Besins Healthcare and research support from Bayer, Lilly and Lawley Pharmaceuticals, and has participated in advisory roles for Lilly, Besins Healthcare, Ferring and Lawley Pharmaceuticals.

Further reading

1. Yeap BB, Grossmann M, McLachlan RI, et al. Endocrine Society of Australia position statement on male hypogonadism (part 1): assessment and indications for testosterone therapy. Med J Aust 2016; 205: 173-178.

2. Yeap BB, Grossmann M, McLachlan RI, et al. Endocrine Society of Australia position statement on male hypogonadism (part 2): treatment and therapeutic considerations. Med J Aust 2016; 205: 228-231.

3. Goldman AL, Pope HG, Bhasin S. The health threat posed by the hidden epidemic of anabolic steroid use and body image disorders among young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: 1069-1074.