Ovulation induction: when and how to use it

Anovulatory infertility should prompt investigation and treatment of endocrinopathies. With monitoring, ovulation induction using oral or injectable medications results in good pregnancy rates and has a low risk of multiple pregnancy.

- Oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea are hallmark signs of anovulation.

- Identifying and correcting underlying endocrine disorders are the first steps in treating anovulation, before initiating targeted ovulation induction therapies.

- Clomifene and letrozole are effective treatments for anovulation in polycystic ovary syndrome.

- Follicle stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone injections may be required, especially for hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

- Single ovulation is the goal of treatment.

- Referral of the patient to a fertility specialist is recommended for ovulation induction with gonadotropins or if other fertility factors exist.

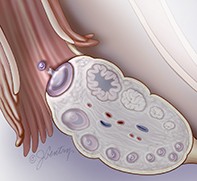

Ovulation is a prerequisite for conception and its absence is the main barrier to parenthood for many couples. Oligomenorrhoea and/or amenorrhoea are hallmarks of anovulation. Disorders of the hypothalamus or pituitary can interrupt the cascade of events that lead to ovulation, as can extremes of body mass index (BMI), thyroid disorders and androgenic conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (see Figure).

Oral agents such as clomifene and letrozole inhibit negative feedback of oestrogen to the hypothalamus and pituitary, stimulating the release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and thus enhancing follicular development in the ovary. If oral drugs are unsuccessful, direct administration of FSH and/or luteinising hormone (LH) can induce ovulation, although careful monitoring is vital to circumvent ovarian hyperstimulation and multiple pregnancy. Metformin and laparoscopic ovarian drilling also promote ovulation.

Most women with anovulatory infertility are able to conceive using low-intervention ovulation induction methods. If multiple follicles persistently develop or other fertility risk factors exist, couples may need to consider in vitro fertilisation (IVF).

When to use ovulation induction

Disruption of the complex hormonal controls which regulate ovulation results in anovulation, menstrual irregularity and difficulty conceiving. The first step is to identify and correct any underlying endocrinopathy before initiating targeted ovulation induction therapies.

Hypothalamic disorders

Hypothalamic dysfunction due to abnormal secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus is a diagnosis of exclusion. Stressful life events, changing time zones, exams, depression and anxiety can cause temporary hypothalamic dysfunction, which usually resolves when the stressor is relieved. FSH and LH levels are often in the normal range but their pulsatile release is abnormal.

Low BMI (<18 kg/m2 or ≥10% below ideal body weight) suppresses hypothalamic function, leading to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (low FSH, LH and oestradiol values). This may be self-limiting and may resolve with weight gain. Careful screening for eating disorders is required and if anorexia or bulimia nervosa are suspected, referral to a specialised multidisciplinary team is obligatory. Weight gain improves FSH and LH secretion in women with anorexia, but about 30% of these women will need gonadotropic ovulation induction to conceive.1

Intense participation in sports that are associated with low BMI and high lean body mass, such as athletics and gymnastics, can result in exercise-induced hypothalamic hypogonadism. Pulsatile GnRH secretion is disrupted when energy expenditure exceeds supply. Moderating exercise may normalise the hypothalamic–pituitary axis and improve responsiveness to clomifene and letrozole. However, ovulation induction with FSH and LH will be needed if there is an oestrogen deficiency.

Congenital hypothalamic disorders

Women with Kallmann’s syndrome have hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, anosmia and primary amenorrhoea. Mutations in several genes impair cribriform plate formation and dislocate GnRH-secreting and olfactory sensory neurons at the pituitary stalk. Referral to a geneticist to discuss the inheritance risk to offspring is recommended, and gonadotropin administration is necessary for fertility.

Rare inactivating mutations in the GnRH receptor gene can produce pituitary unresponsiveness to GnRH. Genetic analysis can be considered, although empirical FSH and LH treatment will effectively induce ovulation.

Structural hypothalamic abnormalities

Tumours, vascular accidents and toxoplasmosis can functionally damage the hypothalamus. Abnormal neurological findings should prompt magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify hypothalamic lesions. An opinion from a neurosurgeon is obligatory. Ovulation induction can be considered after treatment and an evaluation of the risks of pregnancy.

Disorders of the pituitary

Hyperprolactinaemia

Physiological hyperprolactinaemia occurs during breastfeeding and can help with spacing of pregnancies. Psychotrophic medications can also induce hyperprolactinaemia. Other than these causes, hyperprolactinaemia is usually a sign of the presence of a pituitary prolactinoma, although it can coexist with thyroid disease and PCOS.

Hyperprolactinaemia inhibits GnRH secretion, suppressing FSH and LH release, which impedes follicle development. Large prolactinomas compress the optic chiasm resulting in bilateral hemianopia. If oestrogen levels are sufficient, galactorrhoea may be present. A single moderate-to-high prolactin level should be followed by a repeat test while fasting. If prolactin levels remain below 1000mU/L, no treatment is required. Prolactin blood levels above 1000mU/L should trigger MRI of the pituitary and treatment with a dopamine agonist.2 A neurosurgical opinion should be sought if a prolactinoma that is larger than 3cm is identified.

Cabergoline has fewer side effects and restores prolactin levels more effectively than bromocriptine.2 Cabergoline 0.25mg twice a week is started, then titrated up in 0.25mg increments until prolactin levels (measured monthly) are normalised. Ovulation and regular menstruation typically recommence spontaneously. Cabergoline should be stopped in pregnancy and breastfeeding.3

Other hormone-secreting and nonfunctional pituitary adenomas

Spontaneous development of multiple follicles, in conjunction with high FSH and oestradiol levels, characterise FSH-secreting pituitary adenomas. These adenomas are rare. Adenomas that secrete thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and growth hormone are distinguished by hyperthyroidism, Cushing’s disease and acromegaly, respectively. Serum TSH, prolactin, FSH and LH levels should be measured in all anovulatory women. Any clinical or radiological suggestion of a pituitary adenoma should trigger measurement of free thyroxine levels, a midnight salivary cortisol level (to diagnose Cushing’s disease) and insulin-like growth factor 1 levels (to diagnose acromegaly). Expert endocrinological advice should be sought. Surgical resection of an adenoma is likely to regularise pituitary function and spontaneous ovulation. However, if excess tissue is removed, pan hypopituitarism results, necessitating pituitary supplementation and gonadotropin ovulation induction.

Other pituitary disorders

‘Empty sella’ syndrome is seen radiologically when cerebrospinal fluid fills the sella turcica, flattening the pituitary gland against its walls. Although it is usually a complication of adenoma resection, a congenital defect in the sella membrane can rarely occur, which permits leakage of cerebrospinal fluid into the pituitary fossa. Gonadotroph function may be adequate but, if compromised, gonadotropin ovulation induction is indicated.

Peripartum conditions such as Sheehan’s syndrome (acute infarction of the pituitary gland after post-partum haemorrhage, that presents as inability to lactate with pan hypopituitarism) are rarely seen. Similarly, lymphocytic hypophysitis (leucocyte infiltration of the pituitary in association with hyperprolactinaemia) is an autoimmune peripartum condition associated with hypopituitarism. Both require treatment from specialist endocrinologists, and both require gonadotropin ovulation induction.

In haemochromatosis, transferrin-mediated iron uptake from the gut is increased when a gene mutation disrupts transferrin regulatory mechanisms. The gonadotrophs (which are susceptible to iron overload) fail, leading to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and this necessitates gonadotropin ovulation induction. Elevated fasting transferrin saturation levels reveal the condition, and should prompt referral to a haematologist and repeated phlebotomy and chelation therapy.

Disorders of thyroid metabolism

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism (high TSH and low thyroxine levels) is prevalent in women with irregular menstrual cycles who are attempting conception. Hypothyroidism induces hypothalamic secretion of thyrotropin-releasing hormone, which increases TSH and prolactin release. GnRH-mediated FSH and LH production are inhibited and ovulation is disrupted. Hashimoto’s disease (antithyroid antibodies) is the most common aetiology, but infection, iodine deficiency and thyroid tumours can cause hypothyroidism.

Because hypothyroidism is associated with miscarriage, growth restriction and diminished cognitive function in children, adequate thyroxine supplementation is crucial during fertility treatment and pregnancy. Thyroxine requirements are 25 to 30% higher in pregnancy, and subclinical hypothyroidism (raised TSH with normal thyroxine levels) should be treated to ensure that TSH levels remain under 2.5mIU/L during the period of fertility treatment and in early pregnancy.3 Iodine supplementation is also recommended.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism (high free thyroxine and/or triiodothyronine and low TSH levels) is uncommon in women of reproductive age. Grave’s disease (characterised by anti-TSH receptor autoantibodies) is the most common cause. Referral to an endocrinologist to exclude toxic nodular goitre and thyroid carcinoma is recommended. Thyrotoxicosis is associated with miscarriage, pregnancy-induced hypertension, prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction, so a euthyroid state should be attained before attempting pregnancy.

Androgenic disorders

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Anovulation is most frequently caused by PCOS, which is defined by its symptoms. Different emphases on the gynaecological, metabolic or radiological features of PCOS have resulted in three sets of criteria, from:

- United States National Institutes of Health (1990)

- Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (2006)

- Rotterdam (2003).

The Australian Centre for Research Excellence in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome is developing international consensus on the diagnosis and management of PCOS, which may evolve and consolidate these definitions. The Rotterdam criteria, commonly used by fertility doctors, define women with PCOS as meeting two of three criteria:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism

- polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.

Other causes of anovulation must be excluded.4

In PCOS, GnRH pulse-frequency alterations increase LH and reduce FSH secretion by the pituitary, causing a high serum LH:FSH ratio. Elevated LH drives small follicle growth and thecal cell androgen production. Small follicles produce anti-Mullerian hormone, which is elevated in women with PCOS. Anti-Mullerian hormone inhibits FSH activity, suppressing late antral and preovulatory follicle development and ovulation. Multiple mid-sized follicles are seen as polycystic ovaries on ultrasound. Blood tests show elevated androgen indices and low oestradiol and progesterone levels.

Insulin resistance is identified in 50 to 75% of women with PCOS.5 Clinical symptoms include difficulty losing weight, sugar cravings and post-prandial fatigue. Acanthosis nigricans is a hallmark sign. Resistance to insulin enhances triglyceride breakdown in adipocytes, increasing circulating free fatty acid levels. Blood glucose levels increase in response to reduced glucose utilisation in myocytes and amplified gluconeogenesis in the liver, triggering further insulin release from the pancreas.

A healthy diet and exercise regimen improves the symptoms of PCOS and enhances spontaneous ovulation. Insulin-sensitising agents suppress appetite, facilitating weight loss. Bariatric surgery is indicated for women unable to lose weight with other methods or who have a very high BMI.

Nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Inherited deficiencies in the adrenal steroid pathway, most commonly a partial deficiency of the 21-hydroxylase enzyme, underpin nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Reduced cortisol production up-regulates pituitary ACTH secretion, leading to adrenal hyperplasia. Steroid pathway constituents are metabolised through alternative routes in the adrenal glands, which leads to hyperandrogenism. Early onset hirsutism or a family history of CAH should prompt an early morning 17-hydoxyprogesterone test. The ACTH stimulation test further evaluates moderately elevated 17-hydoxyprogesterone levels. Due to the risk of classical CAH to offspring, referrals to an endocrinologist and a geneticist are advised. Clomifene, letrozole or FSH can induce ovulation, although glucocorticoid supplementation may improve their efficacy.

Cushing’s syndrome

Clinical suspicion triggers screening for Cushing’s syndrome using a midnight salivary cortisol test, a 24-hour urinary-free cortisol test, or a 1mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test. If the test is positive, referral for an expert opinion from an endocrinologist is vital for decisions on further confirmatory tests. Primary Cushing’s syndrome can be distinguished from the secondary adrenal response to excess pituitary or ectopic ACTH by using low-dose and high-dose dexamethasone suppression tests. MRI and ultrasound imaging of the pituitary and adrenal glands may locate the underlying lesion. Surgery may be required before fertility treatment can be considered.

Androgen-producing tumours

Extremely high testosterone levels coexisting with virilisation, clitoromegaly and male-pattern hair loss indicate unregulated androgen secretion from an ovarian or adrenal tumour. Ultrasound and MRI should be used to locate the tumour, and the patient referred to an endocrinologist and a surgeon.

How to use ovulation induction

Oral ovulation induction agents

When endocrine disorders are treated and anovulation persists, clomifene and letrozole can induce ovulation in women with normal endogenous oestrogen levels. Clomifene binds for an extended time to the nuclear receptor of oestrogen, interfering with receptor recycling and reducing the effect of oestrogen on cells. Letrozole inhibits aromatase, impeding the conversion of androgens to oestrogen. Depressed oestrogen activity stimulates pituitary FSH release and induces ovulation.

Starting between day 2 and day 5 of the menstrual cycle, clomifene 50mg or letrozole 2.5mg is initially given for five consecutive days. Transvaginal follicular scanning and measurement of the oestradiol level are performed six days later, and these will show the dose response. If no follicles develop, the dose is increased by one tablet daily for another five days. This pattern of tracking is repeated until follicles develop or a maximal dose of 150mg clomifene or 7.5mg letrozole is reached. If one or two follicles grow, the cycle is either tracked to ovulation by identifying a natural LH surge, or ovulation is triggered using human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) when the dominant follicle is larger than 18mm. If two follicles grow, the risk of twins is 2.8% (the absolute rate) but this translates to a 17% risk if pregnancy occurs.6 These risks must be explained and consented to by the couple. If there are three or more dominant follicles larger than 14mm, the couple is advised to avoid intercourse and multiple pregnancy. If anovulation persists at maximal doses of clomifene or letrozole, or conception has not occurred after three to six months, a referral to an assisted reproductive technology unit for further investigation, and treatment should be considered.

When clomifene is used over six to nine cycles, ovulation rates are 70 to 80% and pregnancy rates are 70 to 75%.7 A recent network meta-analysis showed a slight benefit with letrozole use.8 This could be because the aromatase-suppression effect of letrozole is shorter acting than the oestrogen receptor-suppression effect of clomifene. As endometrial proliferation rebounds more quickly after cessation of letrozole, implantation may be enhanced. Initial evidence that letrozole was associated with congenital abnormality has been disproven.

Insulin-sensitising treatments in PCOS

Metformin is the insulin sensitiser of choice, because it improves glucose control and enhances ovarian responsiveness to FSH. Although metformin is less effective in isolation than clomifene, metformin and clomifene together increase ovulation and pregnancy rates in women who are unresponsive to clomifene alone.8 The miscarriage risk conferred by PCOS may also be moderated by metformin.

The side effects of metformin include nausea, diarrhoea and bloating. To improve tolerability, a low dose (150 to 500mg) is started, which can be increased to 1000 to 2000mg in divided doses, slowly over three to four weeks. Metformin is contraindicated in liver and renal disease because of the risk of lactic acidosis. No harm has been identified with the use of metformin in pregnancy, but information is limited and advice should be taken from treating obstetricians and obstetric physicians.

The natural sugar myoinositol improves insulin sensitivity, lowers androgen levels, enhances weight loss and reduces the incidence of gestational diabetes in women with PCOS. Limited evidence suggests similar improvements in ovulation and pregnancy rates and a better side-effect profile compared with metformin,9 but more research is needed. Myoinositol is often available in compounded forms and is an alternative insulin sensitiser when gastric side effects limit metformin use.

Thiazolidinediones (rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) are weak insulin sensitisers that have been trialled in women with PCOS. Animal studies have shown adverse effects in pregnancy, making it difficult to justify their clinical use.

Laparoscopic ovarian drilling

At laparoscopy, electrocautery or laser vaporisation are used to drill four to five holes into each ovary. Reduced androgen and inhibin levels then enhance FSH release and folliculogenesis. At 12 months, the rates of ovulation, pregnancy and livebirth were similar to the corresponding rates with FSH ovulation induction, but ovarian drilling resulted in lower multiple pregnancy rates. This procedure is most successful in lean women.10

FSH injections

Daily FSH injections are very effective but increase the risk of numerous ovulations, multiple pregnancy and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), so this treatment is usually managed by gynaecologists specialising in fertility care. Depending on the woman’s BMI, an initial dose of 25 to 50 mg of FSH is used, and a follow-up transvaginal ultrasound scan and blood test are performed six days later. The dose is adjusted to maximise the chance of a single ovulation, and the monitoring regimen is repeated. Ovulation is frequently activated by a natural LH surge, which is confirmed by a mid-luteal measurement of progesterone level. If timing is critical, HCG 5000IU can be prescribed to initiate ovulation. Further HCG injections (1500IU every three days) or progesterone pessaries (200mg daily) can be used to maintain the luteal-phase endometrium.

When the ovarian reserve is high, particularly when hyperinsulinism coexists in PCOS, a very small effective FSH dose range is seen, below which no follicles develop, and above which many follicles grow. This threshold can vary from cycle to cycle and is modified by metformin in women with hyperinsulinism. In extreme cases, recommending IVF may be necessary.

In hypogonadotropism and hypo-oestrogenism, FSH and LH are the treatments of choice. An alternative is to use FSH preparations, in combination with either HCG 100 to 150IU daily or LH preparation 75 mg daily, in the follicular phase. An HCG trigger is required because GnRH agonists will not trigger an LH surge when pituitary LH stores are depleted.

Complications of ovulation induction

High-order multiple pregnancy

Conception in an ovulation induction cycle with more than one dominant follicle (larger than 14 mm) risks multiple pregnancy. This risk is best managed by close monitoring, using minimal doses to induce one dominant follicle, and cancelling cycles when multiple follicles develop. If ovulation induction cycles are repeatedly cancelled, IVF is recommended because the risk of multiple pregnancy is reduced by performing a single embryo transfer.

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

Women with PCOS and hypothalamic hypogonadism often have an extremely high ovarian reserve. When excessive FSH is given, multiple ovulations can occur (more than 15 eggs) leading to OHSS. Prolonged HCG stimulation in early pregnancy intensifies the symptoms of OHSS, but metformin and cabergoline can moderate them in IVF cycles.

OHSS is seen rarely in ovulation induction because unifollicular ovulation only requires low FSH doses. The risk of OHSS can be minimised by starting with low doses of FSH, increasing the dose in a stepwise fashion, strictly monitoring the cycle and avoiding conception if multiple follicles develop.

Summary

Ovulation and fertility may be restored solely by identifying and correcting underlying endocrine disturbances. If this is insufficient, oral ovulation agents provide a good chance of conception for oestrogen-replete women. Metformin or laparoscopic ovarian drilling can induce or enhance ovulation. Ovulation induction with gonadotropins is highly successful but carries higher risks of multiple pregnancy and OHSS, and must be well monitored. If pregnancy does not occur in six to 12 months, a referral to a fertility specialist should be offered. ET